In 1975, downtown Portland was dying. Middle-class shoppers, fed up with panhandlers and parking hassles, fled the central city for the big-box malls sprouting up in the suburbs.

Then brothers Bill and Sam Naito took a gamble. They bought an abandoned building at Southwest 10th and Morrison—widely derided as a “white elephant”—with the idea of turning it into an urban shopping mall. Instead of generic national chains, the Naitos recruited quirky local retailers like London Underground, Galadriel Houseplants, Mario’s, and Antique Estate. They stuck 114 parking spaces in the basement. For the grand opening, they held a parade with a hand-drawn fire engine and two brass bands.

The Galleria was a smash hit, luring shoppers back from the suburbs and launching the revival of downtown Portland. It wasn’t the first time Bill Naito defied the doubters.

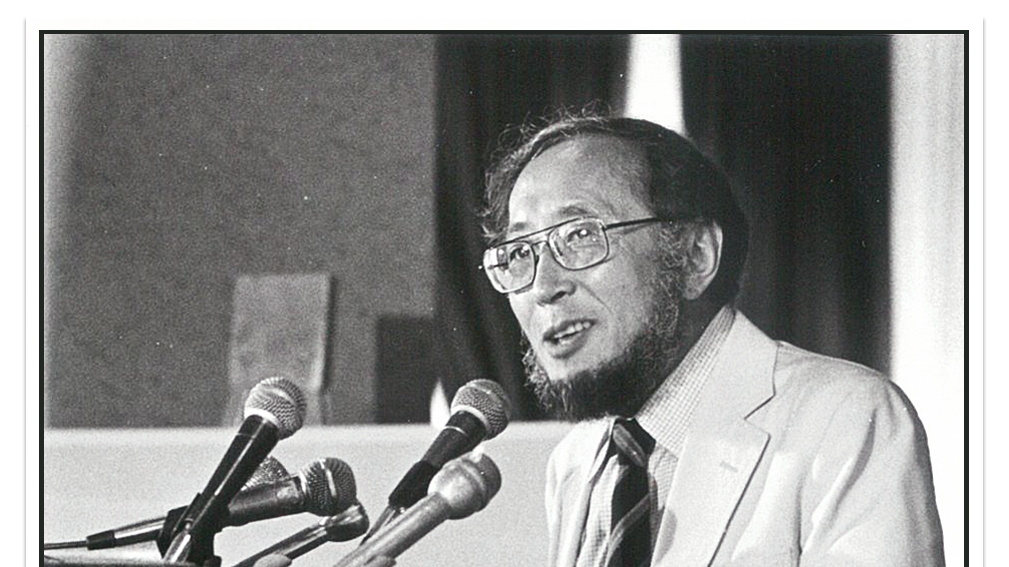

Born in Portland in 1925, a child of the Great Depression, he was a master of doing more with less. His first language was Japanese; he didn’t speak English until he went to grade school. After Pearl Harbor, when racist laws shut down his father’s business, teenage Bill raised chickens in the backyard and sold the eggs.

Naito served in the U.S. Army and attended Reed College and the University of Chicago on the G.I. Bill. His first big project was turning the decrepit Globe Hotel into Import Plaza, selling furniture and tchotchkes from around the world.

Naito had an eye for a deal, but he knew business wouldn’t thrive unless the city thrived. Knowing the stigma attached to the Burnside neighborhood, he renamed it “Old Town” and painted the name on the water tower to promote the idea (it caught on). To lure shoppers, he bought a red double-decker bus and operated a shuttle from downtown to Old Town to Lloyd Center. He was one of the founders of Artquake, an annual arts festival in the South Park Blocks.

Naito played a key role in a staggering list of projects: McCormick Pier, the Pearl District, Saturday Market, Union Station, Montgomery Park, the White Stag Building, the Portland Trolley, the Lan Su Chinese Garden, the Portland Farmers Market. Many of them might never have happened without his relentless cheerleading. “He never gave up,” says his son Bob. “He drove people crazy.”

Naito died in 1996, when downtown was in its heyday. How would he revive it today? “He gave us a road map,” Bob says. “Get creative. Have fun. Build attractions. That model is how he brought Old Town back to life.”

See for yourself: Visit the Japanese American Historical Plaza in Waterfront Park, a few blocks from Portland’s old Japantown. Face the river. Read the poems.

Next Story > 1980: Powell’s Books

Opens in new window

Opens in new window