Matt Dillon sips from a Benson Bubbler right before he rips off a pharmacy on Northwest Glisan Street. That’s our opening for Drugstore Cowboy, Gus Van Sant’s 1989 directorial breakthrough.

This was long before Portland’s chic depiction in Shrill or the twee absurdity of Portlandia, even before David Lynch put the eerie Pacific Northwest on display with Twin Peaks.

The film, set in 1971, shows life on the drug-addled margins of a sparse, soggy Portland. Some might know Van Sant for Good Will Hunting or Milk, but it’s the scrappier films that highlight Van Sant’s impact on this city—the way he hung out in the city’s fringe spaces and humanized down-and-out characters rather than exploited them.

Van Sant moved to Portland as a teen in 1970, attended Catlin Gabel High School, and then returned after film school at Rhode Island School of Design and a stint in Los Angeles.

His directorial debut, Mala Noche, was about the late Portland bard Walt Curtis. Then came Drugstore Cowboy based on a novel by James Fogle, a career criminal (Fogle was in prison in Walla Walla while Van Sant was shopping the script).

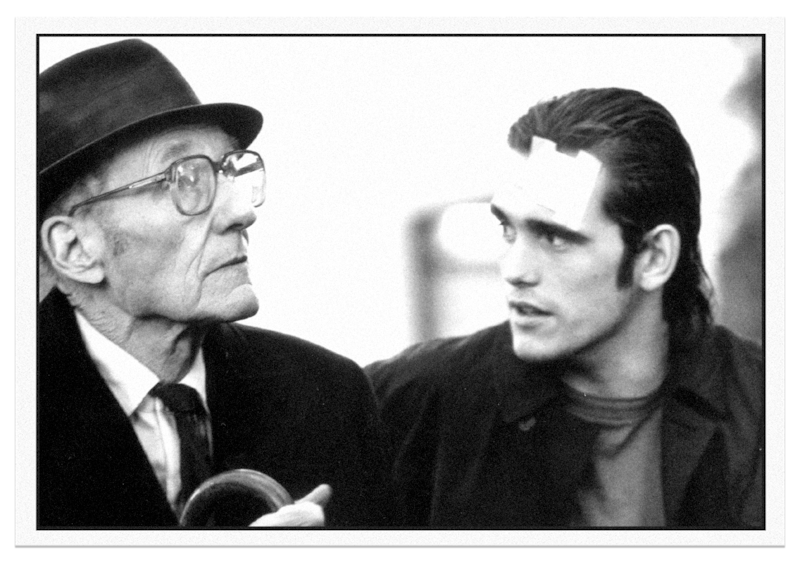

The film revived Dillon’s career and put Van Sant on the map (it also features a charming performance by William S. Burroughs, whom Van Sant met after looking him up in the New York City phone book). Later came My Own Private Idaho, also set on the Portland streets and now a cult classic, and Elephant, cast entirely with local Portland teens improvising their dialogue.

Van Sant left Portland in 2017 for permanent residency in Los Angeles and Palm Springs, but within his decades here, he not only revealed a burgeoning, edgy film industry in Portland, but the city itself—our own Wild West.

Carry it forward: Support new and experimental filmmakers in the city, be it through screenings at Hollywood Theatre, Clinton Street, or Cinema 21, or premieres at Tomorrow Theater.

Next Story > 1989: Kathy Oliver

Opens in new window

Opens in new window