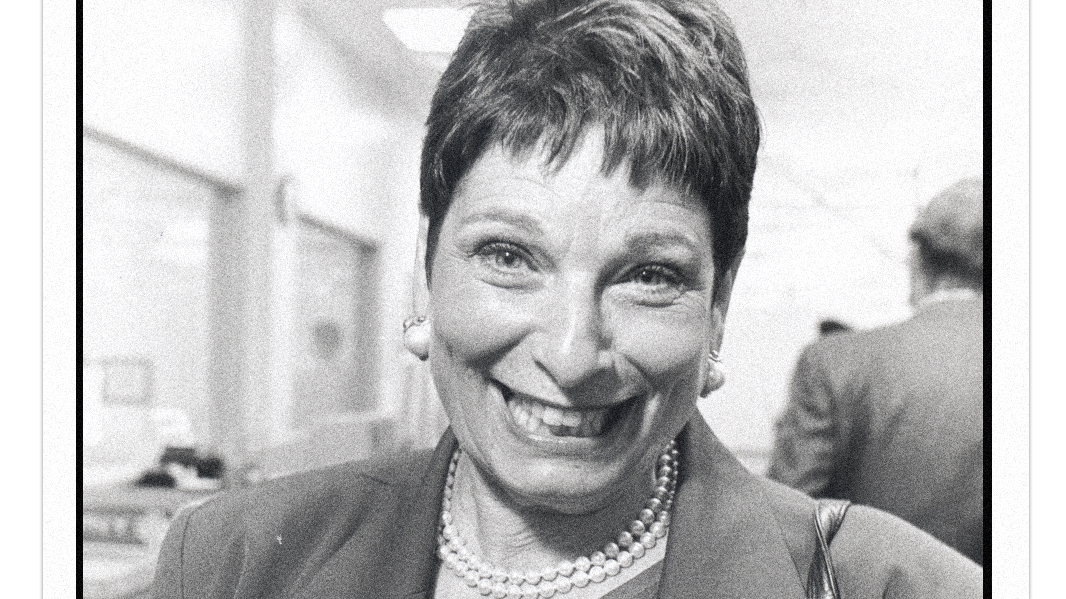

Think big. Think small. Think Vera. In a political career spanning four decades, Vera Katz left an indelible mark on her adopted city. Starting out as a neighborhood activist and rising to mayor, she had razor-sharp instincts, oodles of charm, and a knack for getting things done, whether it was an outsized project like the South Waterfront or cleaning up litter in Laurelhurst Park. Standing just 5 feet tall, she combined the idealism of a Kennedy liberal, the street smarts of a New Yorker, and the drive of the Energizer Bunny. She lavished her boundless talent on Portland like it was the home she never had.

Over three terms as Portland’s mayor, she oversaw the transformation of the Pearl District, the River District, and the South Waterfront. She worked on the aerial tram, the Lan Su Chinese Garden, the Eastbank Esplanade, Civic Stadium, the streetcar, and extending MAX to the airport and North Portland. When property tax limitation measures punched giant holes in public schools’ budgets, she pitched in with city dollars, even though schools weren’t technically the city’s responsibility.

Katz was a transplant. Born in 1933 in Dusseldorf, Germany, she and her Jewish family escaped the Nazis by fleeing across the Pyrenees on foot. She arrived in New York City barely speaking English. “She grew up in a world of tumult and dislocation,” says her son, Jesse Katz. “It tore her childhood apart.” Katz earned a master’s degree in sociology from Brooklyn College, married artist Mel Katz, and moved to Portland, where she licked envelopes and campaigned door to door in 1968 for Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy.

Kennedy’s assassination propelled her into political activism. She wrote a scathing report about conditions for farmworkers in the Willamette Valley. She banged pots and pans outside the City Club to protest its men-only policy. Derided by The Oregonian as a “militant housewife,” she won a House seat in the state Legislature in 1972 and commuted to Salem by bus (she never learned to drive).

She endured relentless sexism in Salem, where male lawmakers routinely underestimated her, according to Beth Slovic, an Oregonian editor who’s working on a biography of Katz. “Vera did not ignore the sexism or excuse it,” Slovic says. Instead, she used it to her advantage, outworking and outflanking her befuddled opponents. She eventually secured the votes to become speaker of the House and drove through a truckload of progressive legislation. But all that was just a warmup for her biggest role: In 1992, she was elected mayor of Portland.

It was a heady time. Portland was climbing out of the 1990 recession. Bill Clinton had just been elected president. Anti-gay Measure 9 had gone down in flames. Young creative types flocked to the city, drawn by the rivers and mountains, cheap rent, a flourishing tech sector, an epic music scene, and a quirky civic vibe. “Come for the fly-fishing, stay for the strip clubs” went a popular bumper sticker. Portland felt like a city with a future.

Katz was the woman of the hour. Her liberal street cred matched the city’s progressive DNA. In a town where distrust of authority ran deep, she was a consensus builder. “She was really good at sitting down at the table with people and figuring out what they needed,” Jesse says. “She realized that people needed to go back home with a win.”

And she was tough. A defining moment came in February 1996, when a freak warm spell and a massive storm pushed the Willamette River to flood stage and beyond. Swollen with snowmelt, the angry river kept churning and rising until it threatened to overtop the westside seawall and inundate downtown. Katz declared an emergency and called on volunteers to help build a sandbag wall from the Hawthorne to Steel bridges. Thousands of Portlanders came out and pitched in, and she thanked them all herself, striding along the waterfront in a purple raincoat. In the end, the river receded inches before it reached the sandbags, but “Vera’s Wall” cemented her reputation as a decisive leader.

Katz saw the big picture, but she also sweated the details. “At night she would read every letter sent by every citizen and every report sent by every bureau,” former City Commissioner Mike Lindberg said at her funeral.

The best way to feel her mark on Portland? Go for a run on the thing she fought hardest for: the Eastbank Esplanade. See how it connects people and places: the eastside and westside, the city and the river, the parks and the bridges. Feel the subtle motion of the floating platforms as they sway with the current. Dive into the water at the Duckworth Dock. “It nourishes the soul of the city,” Jesse says. “I think about her every time I go there.”

Next Story > 1992: Kathleen Saadat

Opens in new window

Opens in new window