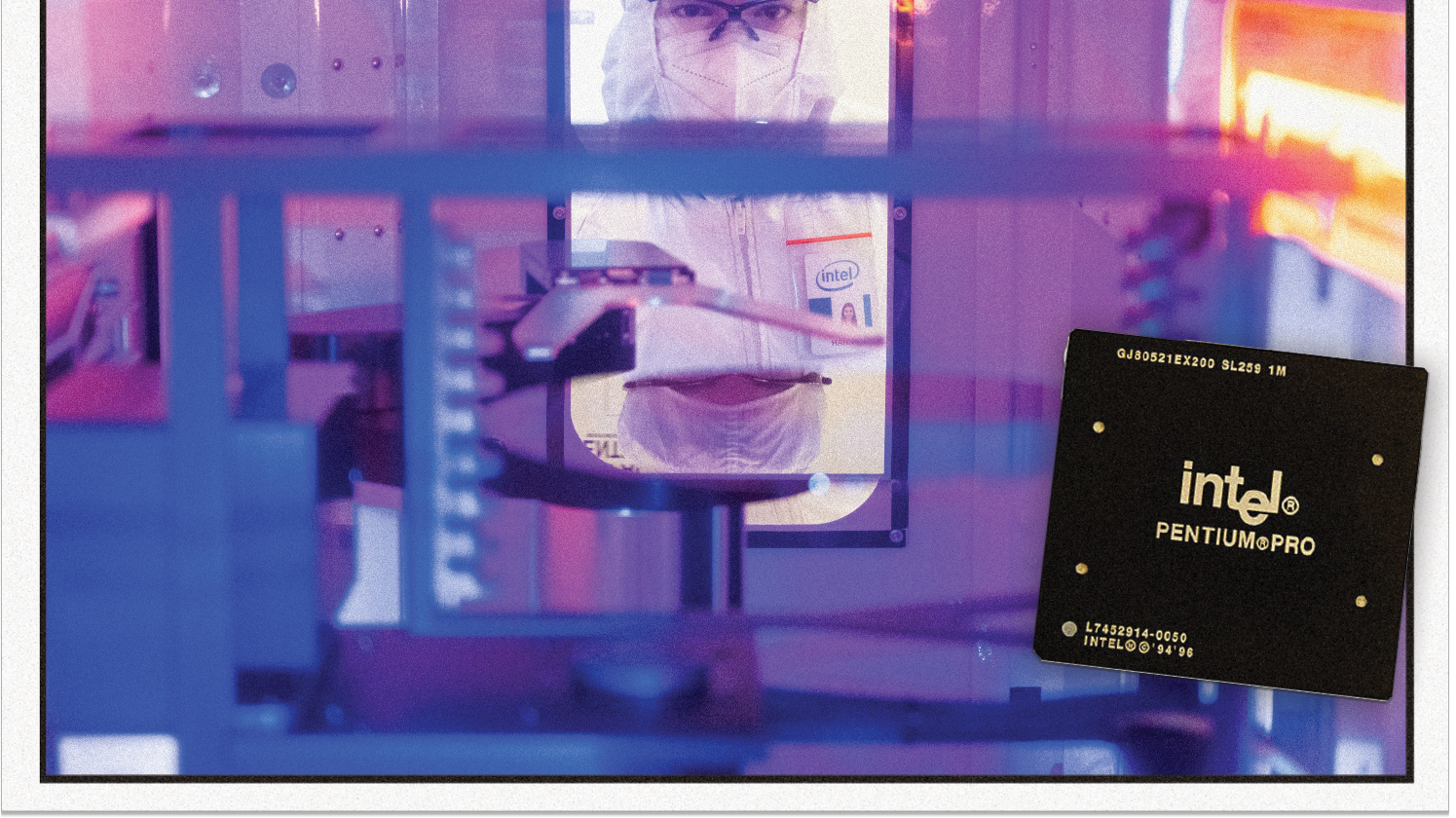

All computers, from the sleekest iPhone to the chunkiest webserver, have something in common: a central processing unit, or CPU. With billions of transistors crammed into a slice of silicon the size of a cracker, these chips are the heart and soul of the digital age. For the past 30 years, Oregon has been a CPU powerhouse, thanks in part to Intel’s Pentium Pro, designed in Hillsboro and released in 1995.

The Pro team, led by engineer Robert Colwell, had a tough assignment. They reckoned Intel could pack about 8 to 10 million transistors on their chip, roughly twice as many as its predecessor, the Pentium. But they couldn’t use that power unless they broke through a bottleneck that had plagued the industry for years. CPUs executed instructions in sequential order, one at a time. You had to wait for one operation to be completed before moving to the next.

Imagine you’re at a giant supermarket, with a long list, in a big hurry. Milk is first on your list, so you dash to the dairy aisle. The next thing is onions, so you run across the store to the produce section. The third thing is butter: You head back to the dairy aisle. Getting through the list will take forever if you keep ping-ponging this way. It’s even worse if you need the butcher to slice a couple of pounds of turkey. You wait at the meat counter for precious minutes, drumming your fingers when you could be filling your cart.

Colwell’s team had a radical insight. Sure, some instructions have to be executed in sequential order. But many don’t. What if they rearranged the list so you pick up all the dairy items in one swoop, then all the vegetables? What if you could keep shopping while the butcher sliced the bacon?

This approach—known as “out-of-order processing”—was a gamble. Some engineers thought it was too complicated. Others worried the CPU would waste too much time performing operations that were never needed (a process known as “speculative execution”).

“We couldn’t be certain it would work at the start,” Colwell says.

The project hit some tricky snags. Halfway through, the engineers learned they’d get only about 5 million transistors. Squeezing all the components onto the chip was a constant headache. (At one point, the Pro team ran out of room and sketched a compromise solution on a napkin at a Chinese restaurant.)

The Pro was not an instant hit. The complex design was tough to manufacture, which kept yields low and prices high. Performance of the early models was sluggish. But once the teething troubles were out of the way, the Pro was lightning fast. It soon became the workhorse of the high-end servers behind the emerging phenomenon known as the Internet and served as the model for all of Intel’s successor chips.

The Pro also pushed the Silicon Forest to the forefront of semiconductor research and manufacturing. Oregon’s tech sector now boasts 6,000 businesses employing 80,000 people at an annual average wage of $125,000 and generating $12 billion in exports.

Intel’s in a slump right now. Its stock price has cratered, and it has announced a big round of layoffs. Nonetheless, Colwell still thinks Silicon Forest has the ingenuity and know-how to lead the way in building the next generation of chips. “It’s a tall order,” he says. “I hope for many reasons that they can do it.”

See for yourself: Fire up an old copy of Quake and blast some zombies.

Opens in new window

Opens in new window