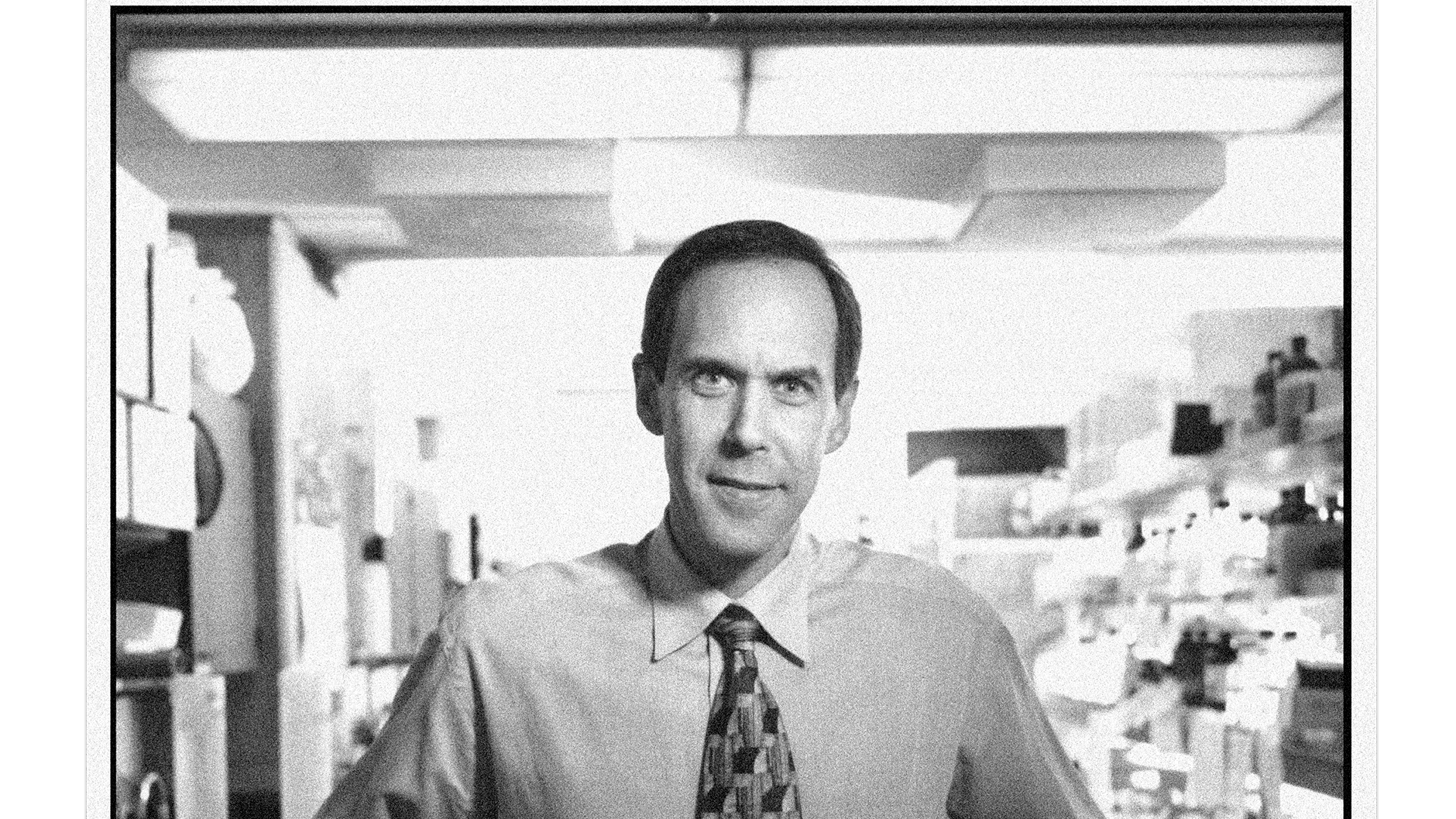

For most of the 20th century, doctors treated cancer by hitting it with everything they had. Radical surgery, high-dose radiation, brutal chemotherapy. Even when it worked, the collateral damage was severe. Chemo didn’t just poison cancer cells, it poisoned all cells. Being a cancer doctor back then was like swinging at a light bulb dangling from a high ceiling, according to Dr. Brian Druker. “Cancer is like a light bulb is stuck on, and the switch doesn’t work,” he says. “So they put you in a room and they gave you a baseball bat and said, shut off this light. And you swung and swung and missed and missed, and after a while, you came out and said, I need a bigger bat.”

Druker had a different idea: fix the switch. Cancer happens when a single cell in the body goes haywire and starts dividing and multiplying out of control. What if you targeted the haywire cells and left the normal ones alone? He spent several years working on this problem in Boston, but the reception was stony. “People said, that’s never going to work,” he recalls.

Druker didn’t listen. In 1993, he moved to Portland to pursue his research at Oregon Health & Science University. “Portland had a much more entrepreneurial, pioneering spirit,” he says. “It was, yes, that makes sense. Let’s give that a try.” By then, he was focused on chronic myelogenous leukemia—a type of cancer where white blood cells develop a specific mutation in a protein on the outer skin of the cell. If he could somehow target the mutant protein, Druker reasoned, he could shut down the cancer. He worked with chemists at Novartis to develop a drug that would bind to the mutant protein like a key in a lock.

Novartis produced a compound known as imatinib that worked in the test tube. It worked in mice. It worked in rats. But would it work in humans? In 1998, Druker tried the drug on the first human volunteers—patients with CML who had months left to live. The results were phenomenal: 30 out of 31 patients showed dramatic improvement. Imatinib (now known as Gleevec) had turned a fatal disease into a manageable condition. Better yet, it showed that you could treat cancer with drugs specifically designed to lock on to mutant cells, opening up a new era of targeted therapy. Since then, Gleevec has saved hundreds of thousands of lives, and targeted therapy is now used to treat dozens of types of cancer.

Today, Druker is the CEO of the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute. Looking forward, he says some of the most promising ways to fight cancer include early detection (catching it when it’s easier to treat) and early prevention (catching before it even begins). To keep making progress, Druker says, the federal government needs to keep funding research. But as a society, we also need to focus on STEM education. “We need to inspire more young people to pursue careers in science and medicine,” he says. “We have to keep asking, what are the big problems and how can we make a difference?”

Opens in new window

Opens in new window