Naked bicyclists, this is your summer.

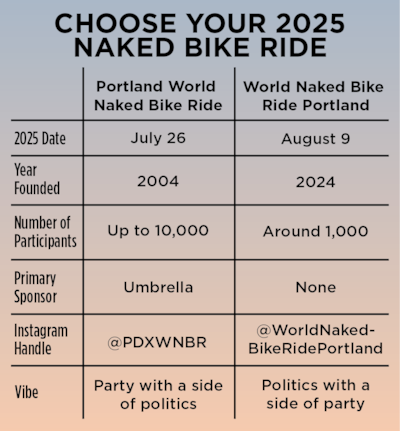

Starting in 2025, and for the foreseeable future, the Rose City will host rival World Naked Bike Rides. The first one, the Portland World Naked Bike Ride on July 26, is the original one in town. It started in 2004 and draws up to 10,000 participants. It goes by PDXWNBR for short and is sponsored by the nonprofit organization Umbrella.

The second ride takes place two weeks later, on Aug. 9. The World Naked Bike Ride Portland—with the city moved to the end of the name to somewhat distinguish it from its predecessor—is a smaller ride of about 1,000 with a more pointed political message, now in its second year. It includes a “die-in” in front of Zenith Energy fuel company downtown, a form of protest in which people lie down and play dead to bring attention to a cause. Both offer music, a fun atmosphere, and the chance to catch a well-placed breeze.

What gives?

The confusing nude biking landscape is the result of a fracture in leadership that happened in 2024. Citing the need to build a bigger volunteer team and renew the event’s focus on rider safety, organizers of PDXWNBR canceled the 2024 ride, which would have marked the 20th anniversary of the event. Refusing to let the ride take the milestone year off, a smaller group of volunteers broke off and led a ride in September anyway.

That was the official narrative, at least. In WW’s multiple interviews with sources on both rides, a more complex picture emerges of hurt feelings, backstabbing and stolen rides.

Meghan Sinnott, a longtime ride organizer involved in Bike Summer, Pedalpalooza and more, was at the top levels of PDXWNBR when last year’s ride was canceled. The bike community has a code of conduct when planning rides to avoid overlapping dates and themes, Sinnott says. If someone wanted, for example, to resurrect the popular David Bowie vs. Prince ride after it died along with its namesakes in 2016, she says, they would reach out to the original ride leader, ask permission, and perhaps invite them to attend as an honored guest.

The way WNBR Portland came about last summer was nothing like that, Sinnott says.

“There’s a deeper, weirder thing happening,” she says. “It’s a scary rift in the community because it’s a new thing, and it feels like something we’ve never dealt with before.”

For their part, WNBR Portland’s leaders say World Naked Bike Rides are a global but decentralized movement and they have every right to take that name and ride with it.

“It’s sad that there is an attempt to police bike rides,” says Máximo Castro, the new ride’s spokesman. “We’d like to focus our energy on an actual cause and the issues and joy being a form of protest because that’s really what it should be.”

For those who have not participated in or spectated at one of these rides, the “naked” part is not hyperbole. Organizers encourage riders to go “as bare as you dare.” And while some people wear bikinis or pasties or booty shorts, many more are buck naked, bringing up countless questions over the years about hygiene and the discomfort of bicycle seats. It’s legal because the bike ride is officially a protest against our nation’s dependence on fossil fuels, and protests are protected under the First Amendment.

Germán Jara attended his first PDXWNBR a decade ago after moving here from Washington, D.C. He didn’t tell anyone he was attending because it was a personal decision, part of his journey toward self-acceptance. Portland is the first place Jara has lived as a Hispanic man where he feels like he belongs, he says. PDXWNBR is a big part of that.

“I felt like I was seen for me, and not as a person of color,” Jara says, getting emotional. “That’s why the bike ride is so important to me—it’s about inclusivity and welcoming everyone for who they are. It’s about ‘I’m OK being myself.’ Sorry, I’m tearing up.”

PDXWNBR is one of the oldest and largest naked bike rides in the world. The movement began in the early 2000s in Spain and Canada to promote safer cycling and body positivity and to protest oil dependency. By 2004, the concept had spread to a handful of other cities, including Portland, London and Seattle. The ride now operates in 36 countries.

Putting on the ride each year is a massive lift, Jara says, and it used to be on the shoulders of a few unpaid people, including Sinnott. It involves applying for city permits like a noise code variance, training “corkers” (volunteers who stop traffic at intersections as the ride passes), communicating with neighborhood associations and the media, and organizing porta-potty deliveries and park cleanup afterward. When Jara heard the 2024 ride was canceled for lack of volunteers, he raised his hand to be the “lead wrangler” on the all-new 2025 PDXWNBR team, the person who oversees all the committees and keeps the ride organized.

But another ride was already in process.

The fallout traces back to meetings that happened in the spring of 2024. A ride leader who asked to be identified in this story as “Spartacus”—all members of the WNBR Portland team of 25 volunteers (other than Castro) are going by Spartacus for personal safety reasons, they say—was leading the 2024 PDXWNBR. Sinnott and other longtime volunteers looked at where Spartacus was in the planning stages of the event and were not satisfied with organizers’ progress. Volunteers in three key positions had just quit, Spartacus didn’t have a route locked down, and the ride was in three months. PDXWNBR pulled the plug.

“That was nothing I ever wanted to do, and we did it anyway,” Sinnott says. “I dry heaved for weeks thinking about it.”

But a ride did indeed happen—WNBR Portland’s first—with Spartacus at the helm setting the route. Castro had no idea how many bikers to expect and was pleased by the turnout and the political impact of the die-in, including the city opening up a public comment period on Zenith shortly after the ride. Politics were finally front and center in a way Castro felt was lacking at previous PDXWNBRs. But some nasty internal politics were also on display, according to Spartacus. “We don’t really have the voice that they have, their clout,” Spartacus says of PDXWNBR. “And if we did have their voice and clout, the very last thing that we would be doing is putting down other people.”

When WNBR Portland started up, confusing the bike community with its similar name and mission, Sinnott hoped it was a one-time retaliatory ride in the absence of a 20th anniversary event. But the recent announcement of the spinoff ride’s return Aug. 9 threatens to deepen the chasm in the bike community, she says.

“Something was off last year, and it has continued to be off,” Sinnott says, who has shifted to an advisory role for PDXWNBR. “It’s what I lose sleep over every night: What is brewing? As a community organizer, there is something amiss. And you never want that.”

Nothing insidious is brewing, Castro says, though leaders from both rides say their social media accounts contain nasty snipes and blocks from the other side. Portland can easily support two naked bike rides, he says, and Castro finds the insinuation that there can only be one tedious. Full-moon naked bike rides happen all year round, he says. On random summer days, people will drum up friends on Umbrella’s app and community ride calendar Shift to go on a last-minute naked bike ride. Every year, people travel to the Rose City from all over the region to participate in world naked bike rides—either one.

The all-new volunteer team, like Jara, welcomes the spinoff ride to the Portland nude cycling scene. “They are very passionate—I definitely admire that and appreciate that,” Jara says. “The more bike rides, the better.”