I was planning to have a fairly normal Thanksgiving this year: Donning my pilgrim costume, popping the turkey-warble CD on the stereo, and having a few friends over. However, it has not been a fairly normal year, so a fairly normal Thanksgiving would have felt disingenuous.

So last week, I convened an emergency meeting of the Olde Portland Preservation Society, and we decided to do something different: host a historically accurate re-enactment of a late-19th-century Portland Thanksgiving.

Related: Thanksgiving 1621 found Portlanders eating camas, wapato, salmon—and maybe a passing seal.

You may have heard of my great-great-grandfather Rudyard Millar, an early Portland ferryman and influential foot masseur. He additionally penned a journal of his daily activities beginning in the early 1880s. One such passage details the festivities from Thanksgiving in 1886, including the recipe for a popular regional dish of the time.

Related: The Journal of an Old Portland Foot Massage Parlor Tycoon Found in Portland City Grill

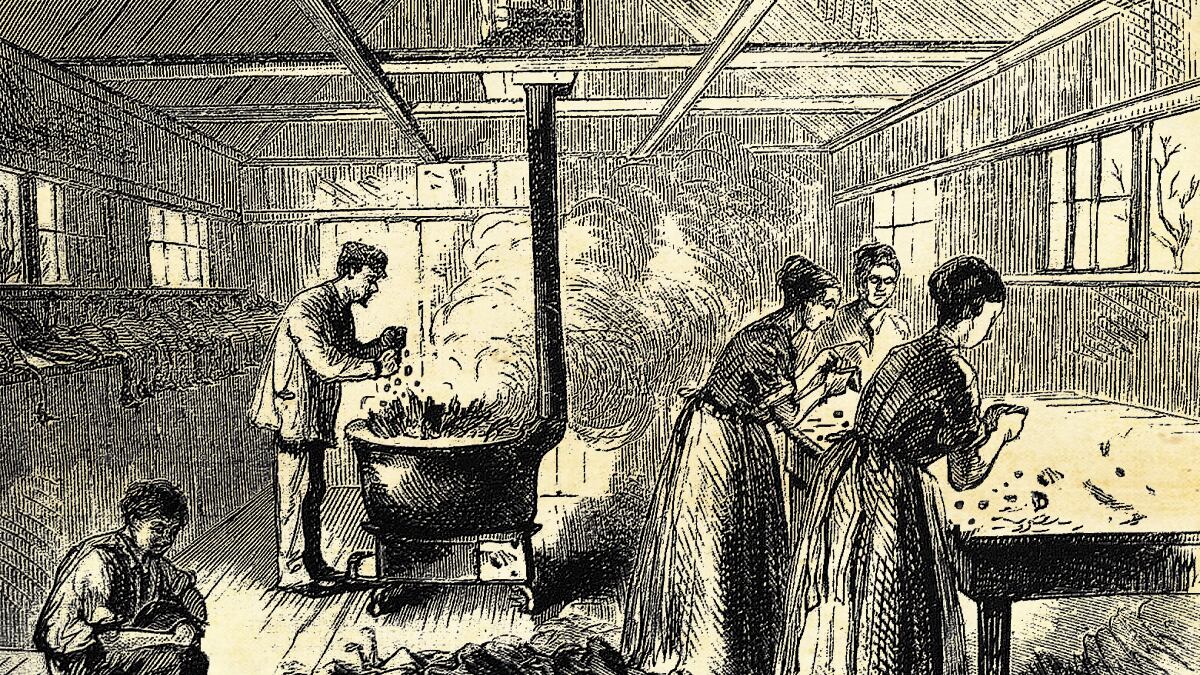

You must remember there was no New Seasons Market in Papa Ruddy's Portland. They had to make do with ingredients that were naturally abundant, and usually everything had to be cooked simultaneously over a single open stove. With this in mind, we acquired a butt of wine (as prescribed by Rudyard's account) and set out to make a cauldron of fig, filbert and oyster stew. For those interested in making this dish, here is the recipe, transcribed exactly as in the journal.

Gather figs for an hour (enough to fill a sack).

Gather filberts for an hour or longer (enough to fill a slightly larger sack than the fig sack).

A princely quantity of fat oysters.

Combine oyster meat with figs in a cauldron. Add water and boil for three days. Remove from heat. Add shelled filberts. Season to taste.

Though I was not an immediate fan of the stew, it grew on me. The sweetness of the figs and the briny minerality of the oysters were an intriguing balance. The filberts added a necessary textural contrast.

Rudyard's journal went on to describe activities for after the meal. A bonfire was built and they danced ecstatically. (We were not able to build a bonfire for our re-enactment, however, because it had rained for several days before Thanksgiving and the ground was wet.)

The rest of his account—which may have been some sort of metaphor or a joke unintelligible to us today—describes a grisly ritual in which straws were drawn and the short straw was offered up as live sacrifice to the gods of Thanksgiving as a token of the group's thankfulness. (We also opted not to include this ritual in our re-enactment.)

I asked the group: If we can't build a bonfire and we're not going to sacrifice anyone, what can we reasonably do? We debated, but could come to no consensus. Finally, someone suggested that since it was getting late and already dark, we should go inside and play Apples to Apples.

Nothing like Apples to Apples existed in Rudyard's journal, I asserted, bristling at the suggestion. But it was no use. Everyone had their hearts set on the game.

"I refuse to be an accomplice to your despicable assault on Portland's rich history," I bellowed at them, going upstairs alone to watch some of season two of Narcos on Netflix.