I must confess: As recently as one week ago, my valise was packed and ready by the front door. I was going to take my leave of you without so much as a goodbye. But don't feel sorry. I was going on a research vacation, the trip of a lifetime, a six-month expedition to the Middle East, a region that admittedly I do not know much about, though if it's anything like Southeast Portland, I'm sure I would have no trouble getting acclimated in no time.

This timing was intentional. I did not want to spend another first of April on this continent. I hoped to avoid that annoying "holiday," which is the bane of my existence and that of distinguished historians everywhere.

Last year on the Day of Fatuousness (or April Fools' Day), I had been on a walk downtown when a stranger approached and said there was a caterpillar on my sleeve. I thanked him, and spent the rest of the afternoon and evening searching far and wide for the exploring caterpillar. It did not dawn on me until early the next morning that the deceitful fellow had been playing me for a gull.

There is also the instance of my colleague and close friend Dr. Clarence C. Chambers, once considered the world's foremost expert on the rich and diverse history of Vancouver, Wash. Dr. Chambers spent years secretly researching an alternative town charter, which revealed that city founders had intended "Vancouver" to be pronounced differently from how we know. Rather than with a harsh "v" consonant sound, they had proposed that each "v" be pronounced as the Romans would, softer, like a "w"—"Wancouwer." I reviewed his paper, and came away impressed with the breadth and precision of his research. I said to him, "Chambers, old man, this will put Wancouwer on the map!"

Unfortunately, his paper was published on April 1, the Day of Fatuousness, causing the Pacific Northwestern historical research community to doubt the veracity of his claims. The resulting controversy cost him his reputation, and Dr. Chambers began seeking solace in the bottle, which cost him his marriage.

Academics in other fields will tell you the same: The professional risk of having one of your papers published on April 1 is simply too great. And that is why I had outlined such a detailed itinerary for my long vacation to the scenic Middle East. I would see all of the sights. The Great Pyramid of Giza. Petra, the ancient stone city. And, of course, the Colossus of Rhodes.

My plans changed when the editors at Willamette Week contacted me to say an important historical story needed my accurate touch. Something about a bear pit. I immediately canceled my flights and hotel rooms and restaurant reservations. When a story demands to be told, I will tell it. So without further ado, here is the story of the bear pit:

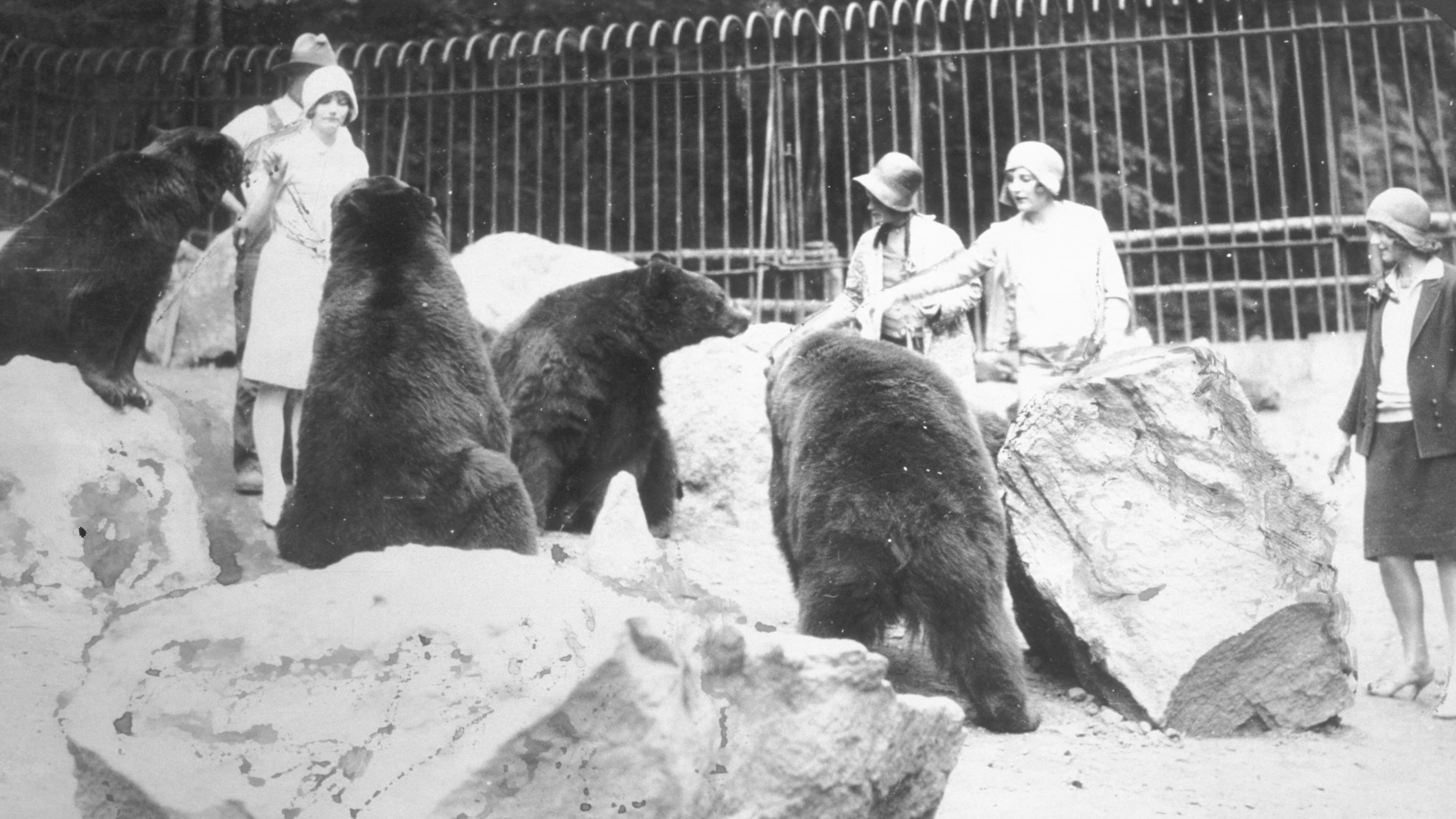

In Washington Park, the present-day location of the Portland Japanese Garden, there was once a bear pit. What is a bear pit, you may ask? Well, it simply is a large pit filled with bears. Portland anti-bear forces would capture the bears—a public safety measure in the early 20th century—and bring them to the pit, where they would live for the amusement of spectators. It was, essentially, a bear prison. The pit was eventually filled, but you can still see the outline of where it was in the koi pond in the Japanese Garden. The Oregon Zoo grew from this bear pit. This city has come a long way—the zoo now has an elephant pit, a goat pit and a giraffe pit, stocked with animals caught in distant places and brought here for our amusement.

This is the truth, and I hope you won't doubt it because of the Day of Fatuousness. Regardless of what the calendar says, serious historians like me will not put their name to falsehoods, amusing though they may be.