Last summer, the Republic Cafe turned 100…ish.

According to city documents, construction on the Chinatown structure was finished in 1922, but the restaurant itself didn’t open until 1930. Newspapers from the period identify a business called Republic Cafe operating as far back as 1919, which may explain the “New Republic” remnants painted on the parking lot entrance. Wai and Sue Mui, co-owners of the restaurant for more than three decades, just relied upon the date printed on the front of Republic menus: Indeed, it’s 1922.

Precise details of the Republic’s origins are far less interesting than the secrets behind its survival. Its Old Town neighbors have largely fallen to boutique hotel developments or tent camps. The Republic’s marching on, the last bar standing amid downtown’s underbelly. It survives without Oregon Lottery terminals or resorting to a second act as a Disneyfied tourist trap hawking glimpses of a long-lost seediness. Forget Jake’s. It’s Chinatown.

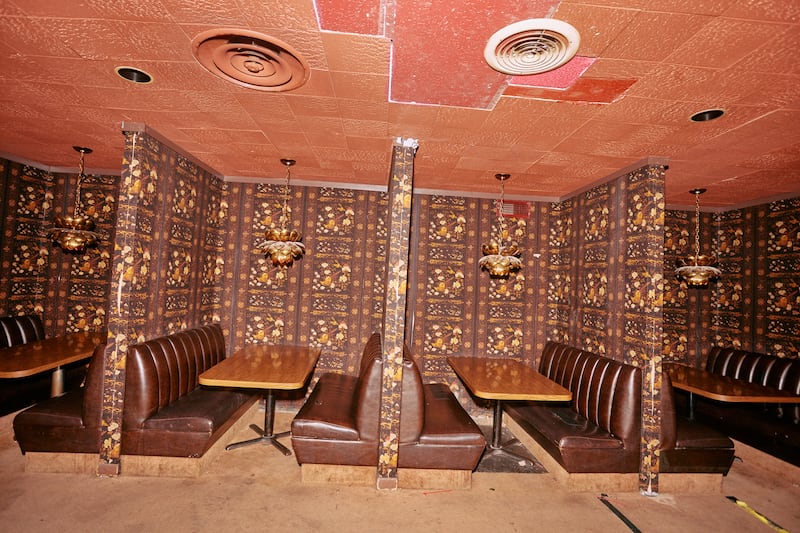

To be sure, the Republic’s kitchen believes any enduring success flows from diligently replicating dishes unaltered from the ‘20s heyday of Cantonese American eateries. Both owners and lounge manager Heather Nissa further credit the 60-some years spent behind the bar by a dearly departed ‘tender. “When Miss Mary was working,” Mui sighs, “very nice customers would stay late. People had their birthdays, wedding parties in the banquet room.”

A certain rough-and-tumble element should be expected. The annals of Republic lore contain as much sweet as unsavory—a cook’s head bisected by a hatchet for every Bud Clark bar floor proposal—but the past decade’s worst years ran particularly dark. “When I started seven years ago,” Nissa recalls, “we had one [police] officer come through, tell everybody he was only here at the new bartender’s request, and walk back out—that was the most help we ever got.”

But the lack of city scrutiny was perhaps a stroke of fortune. Back when the Republic opened, Nissa says, “We weren’t policed like everywhere else, and the Chinese were much more accepting of anybody who came in so long as they spent money and were respectful. The same rules didn’t apply here as they did everywhere else, which led to a beautiful community flourishing.

“Even back in the ‘20s, the rest of Portland was still segregated, you know? People who were Jewish or sexually oriented different than mainstream would come here, and diversity thrived. Patrons who’d normally never even see one another would end up having a good time together publicly at a time where nobody else could. Up until recently, at least, it’s always been the type of place where you’d get a crackhead hanging out with the chief of police. You still never know who you’re going to run into here.”

The Republic’s new minders have embraced that possibility. The once-and-future video poker alcove in adjacent Ming’s Lounge has been repurposed as de facto gallery and chill-out space, while the banquet room now hosts maker fairs and musical acts booked by Nissa’s husband, Mykal Ragonese.

Last autumn’s westward relocation of raver haven Rainbow City into the vacant husk of neighboring Fong Chong has emboldened a freshly bustling nightlife that once more sees the cream of local tastemakers pack Republic to the wee small hours. Now that both Republic and Rainbow City help share the costs of a private security team based around the Society Hotel one block away, the community’s even resumed policing itself.

For Nissa, the rise of the next Chinatown empire comes as welcome vindication:

“The second I walked into the Republic, I knew I was meant to be here. It felt like home—where I belonged, where we all belong.

“There are still boards on the front door. Some benches could be replaced. The neon needs refurbishing. It’s far from perfect and just beautiful that way. There’s no place just like this anywhere in the world, and it’s been that way for a hundred years.”

0 of 11