The ushers at the Schnitz must hate Nick Cave.

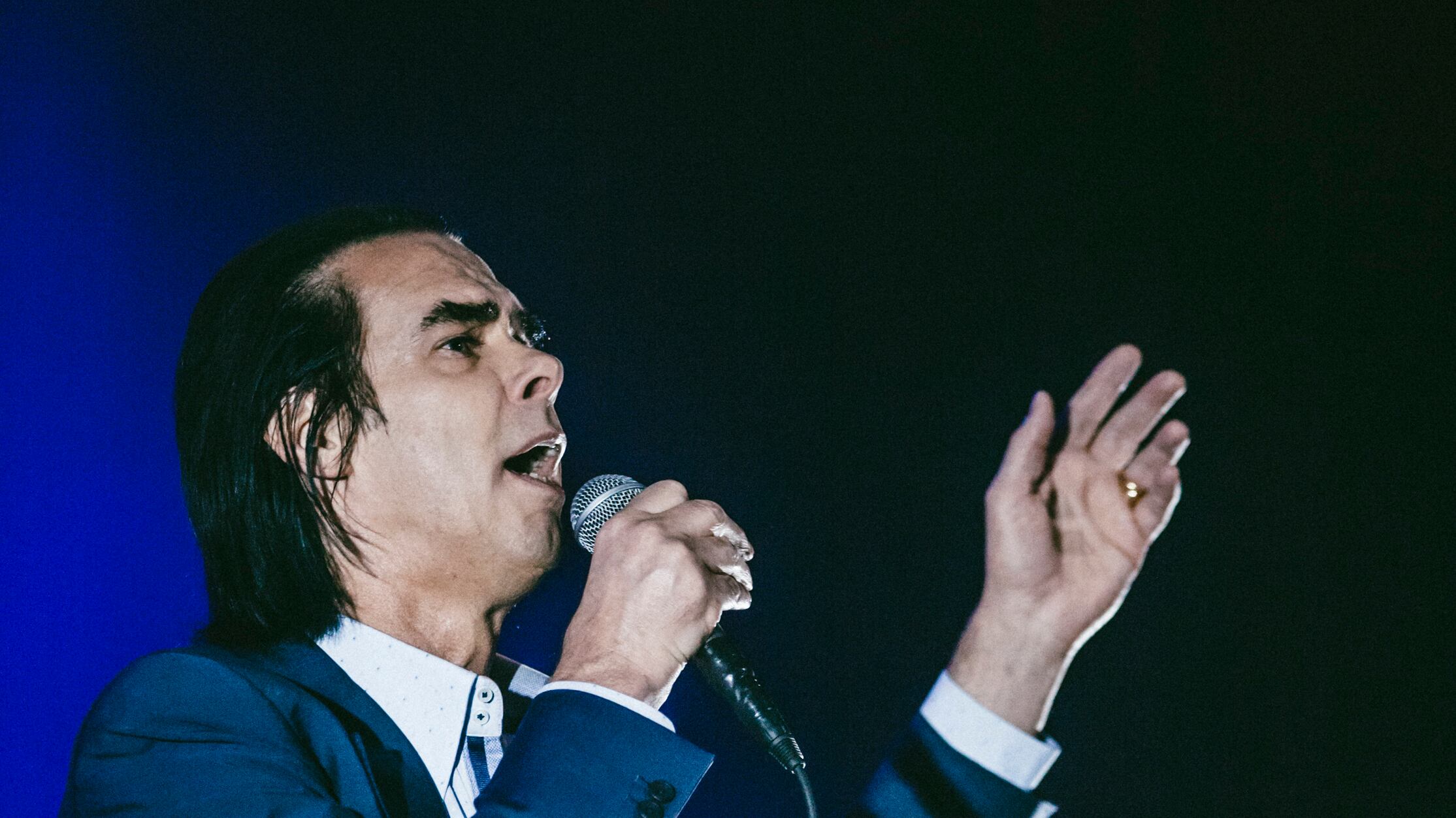

After all, you don't sign up for a gig at Portland's ritziest concert hall expecting to deal with aging, unruly goths in full Beatlemania mode. If the staff had grown soft from too many quiet evenings spent escorting elderly symphony patrons to their seats, Cave, returning to town on June 21 for the second time in three years, made sure they earned their pay. Just as they would clear the aisles of fans clamoring for his outstretched hands, he'd beckon them all back, at one point instructing the crowd to "crush down to the front in a dangerous sort of way." It was a joke, mostly, though danger—or, at least, portentous dread—has long been his stock-in-trade. He might not be playing the kind of clubs that naturally breed chaos anymore, but even in a posh theater, he's going to manufacture some semblance of chaos, one way or another.

Given the last two years of his life, though, it'd be a mistake to classify this as just another spitting, snarling Nick Cave show. In 2015, his teenage son, Arthur, fell to his death from a cliff near his home in Brighton, England, a tragedy that upended the recording sessions of his latest album, Skeleton Tree. Released last year, it is very much the sound of a man staring into a sudden abyss, and if Cave wanted to essentially sit shiva on his first North American tour since the accident, his audience surely wouldn't have blamed him.

And at first, it seemed like that's what we were getting. Taking a seat in front of a lectern—dressed, like the rest of his band, in a well-tailored black suit—he began with "Anthrocene," a nearly ambient drift with profound grief at its core. "All the things we love/We lose," he sang, the line jutting from the barely-there arrangement like a shard of glass on black carpet.

It wasn't long before Cave reassumed his doomsday preacher persona—stalking the stage, flailing his arms, hooting and howling and forcing himself on the audience. But even then, it felt different. He spent the show practically on top of the crowd, reaching out from the stage, sometimes walking across the seats to venture into the throng. It wasn't theatrical confrontation of the sort he's known for—truly, he seemed to be clinging to them.

On "Higgs Boson Blues," he literally placed the audience's hands on his chest and asked, "Can you feel my heart beat?" When people retreated back to their assigned seats, at the behest of the beleaguered theater staff, Cave implored them to return. "You have to," he said, "even if you don't want to." It was a remarkable display of vulnerability from an artist often referred to as the Prince of Darkness—here, he was simply a wounded man, seeking support and solace from a roomful of empathetic strangers.

But if this was a softer, more affectionate Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, the music itself was no less ferocious. Aside from a stretch of foggy ballads toward its end, the two-hour-plus set proceeded with clenched-fist intensity. The noise-punk exorcism "From Her To Eternity," with its infernally plinking glockenspiel, sounded like an apocalyptic Bond theme. Cave added contemporary menace to fan favorite "Red Right Hand," slipping in some not-at-all subtle political commentary: "You see his angry little tweets…"

And for "Stagger Lee," his noisy, profane retelling of a bloody folk legend, the show's themes of communion, catharsis and chaos converged, with Cave inviting dozens of fans—maybe even 100 or more—to fill the stage. Only Nick Cave would incite a dance party for a song about a guy murdering people in a bar. And only he could make it sound like healing.

Photos by Sam Gehrke and Kevin Friedman.

0 of 14