Ken Ward committed his crimes at dawn.

The 60-year-old activist from Corbett, Ore., steered his Jeep Wrangler down a curved road at the outskirts of Burlington, Wash., a town of shopping malls and youth soccer fields about 50 miles south of the Canadian border.

He parked where the road dead-ends, and grabbed a pair of red-handled bolt cutters from the passenger seat.

Ward leaned his elbows on the hood of his Wrangler and bowed his head, silently saying the Serenity Prayer—the one that asks for "the courage to change the things I can."

In the next 11 minutes, Ward would rack up three felony charges and a misdemeanor: burglary, sabotage, assemblage of saboteurs and trespassing.

He freely admits to what he did that morning of Oct. 11, 2016. He shut off the emergency valve of the Trans Mountain pipeline, which delivers crude oil from Canada's Alberta tar sands to Washington state for refining.

At the same moment, protesters in North Dakota, Montana and Minnesota were also snapping locks and shutting off pipelines. They called themselves the Valve Turners. Each brought videographers to record the action.

Ward now faces 30 years in jail—probably the rest of his life. He says the peril facing the planet demands nothing less.

This week, Donald Trump—who has called climate change "an expensive hoax" and pledged to dismantle the nation's environmental regulations—will assume the presidency of the United States. Plans are for thousands of Portlanders to take to the streets in protest. Many more will travel to Washington, D.C., to demonstrate at the inauguration.

Ward says that's not good enough.

"I think protests—even large protests—are absolutely inconsequential," he says. "Trump will welcome them. We need a totally different approach."

Ward says a rapidly warming planet—one that could see further destabilization of the Antarctic ice shelf and rising sea levels under Trump—demands radical action, including breaking the law to stop the flow of fossil fuels. He says the mainstream environmental movement—one in which he worked for 30 years—has failed, and it's now the responsibility of Americans to take action.

"I really think Ken Ward is one of the most important environmental activists of our time," says Boston-based activist and journalist Wen Stephenson, "simply because of his determination, his sheer cussedness and his refusal to take no for an answer."

On Jan. 30, Ward will make his case in a circuit court in Skagit County, Wash., and hope his lawyer saves him from three decades of prison time and thousands of dollars in fines.

He will argue that breaking the law was necessary because the government's actions left him with no other way to stop an assault on the planet.

Ward's protest—and the consequences he faces—are extreme. He fits somewhere between Mahatma Gandhi, whose civil disobedience set India on a path to independence, and members of the Weather Underground, who blew up buildings in the 1970s in a campaign to overthrow the U.S. government. Ward's actions pose a challenge to activists who protest for a weekend and float back to comfortable lives.

Ward is willing to sacrifice the rest of his freedom, one day at a time, to make a point.

He'd like others to follow his example.

"The world is ending," Ward says. "Act freaked out."

Ken Ward lives at the edge of one of Oregon's most beautiful places.

After spending most of his life in New England, Ward relocated in 2013 with his then-wife and their son to Corbett, a town at the western edge of the Columbia River Gorge.

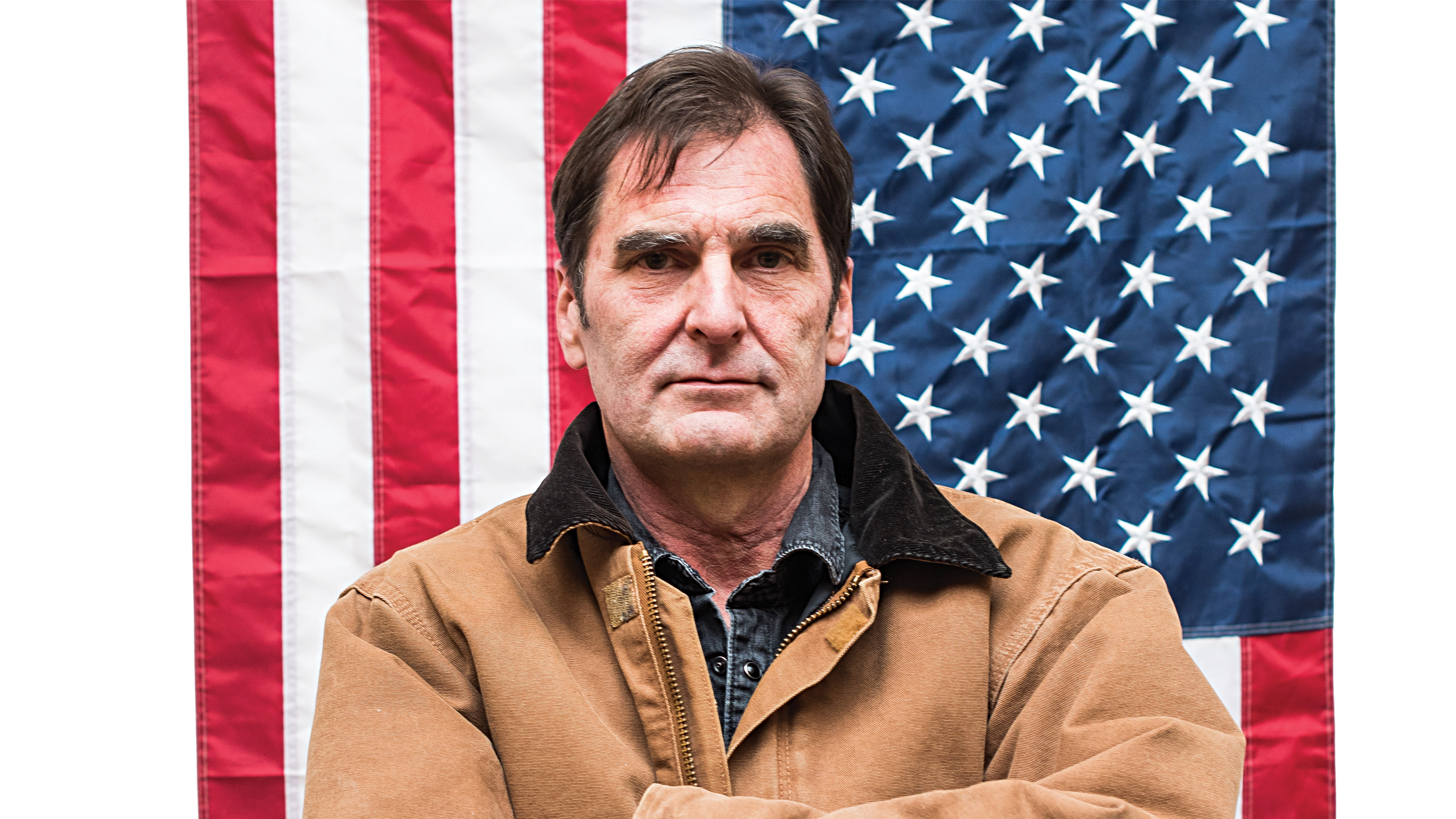

Ward, who at the cusp of retirement age still has dark black hair, thick brows and a persistent 5 o'clock shadow, is easygoing and soft-spoken. He's a devout Christian who attended seminary in the early 2000s. And he considers himself a patriot. He often wears a brown work jacket with an American flag stitched on the sleeve.

"I'm a middle-class, white, male WASP Christian," he says. "And at some level, my nation and my religion and my sense of values have been stolen by yahoos."

He was born in 1956 in Illinois to parents who worked at local colleges. He remembers attending the very first Earth Day in Providence, R.I., when he was 14. "There were speeches and banners and folk songs," he recalls, "and this really exhilarating idea that we could do something."

As a student at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., in 1976, Ward wrote, introduced and lobbied for a state bill that would tie automobile efficiency to motor vehicle registration fees. It didn't pass. He kept going, campaigning against nukes and for bottle deposits.

In 1997, he became deputy director of Greenpeace USA—one of the nation's top environmental positions.

Three years later, he quit, burned out. He became a full-time, stay-at-home dad.

He recalls a bright summer day when he was watching his 3-year-old son, Eli, toddling around their backyard, which overlooked Boston Harbor. On his laptop, Ward was reading a report on climate change.

"I was looking at my little boy playing in the yard," he remembers. "I'm looking at the water thinking, 'What's his life going to look like? Where we live will be an island.'"

For the next six years, Ward looked for a way to fight back. He gave lectures. He spoke at universities. In 2006, he moved into a dilapidated Boston store and renovated it into a low-carbon-impact home.

Ward's girlfriend, Laura Byerly, says he is constantly thinking about climate change.

"I can go and do other things and not worry about it every waking moment," she says. But he can't. "It's hard to support a person like that. It's hard to love them. They're suffering all the time."

Through his Boston-area work, Ward met Jay O'Hara, a young Quaker environmentalist who had been unsuccessfully trying to organize a coal-plant blockade. One night in 2013, during a protest, Ward proposed an idea to O'Hara.

"He says, 'I think we should get a boat and block the coal ship at Brayton Point [Power Station],'" O'Hara recalls. "It was really clear for me. That's exactly what we should do."

On the morning of May 15, 2013, Ward, O'Hara and supporters met on a dock in Newport, R.I. They were about to step on board a 32-foot lobster boat—one they named the "Henry David T." after civil disobedience pioneer Thoreau—when Ward stopped and asked for a prayer. He had brought his Bible.

Ward and O'Hara then cast off, motored and anchored the lobster boat off the coast of Massachusetts in the direct path of a ship carrying 40,000 tons of West Virginia coal.

"We were laughing—if we block a coal ship and nobody blogs about it, did it happen?" Ward says. "We looked at each other and said, 'We're still gonna do it.'"

They dropped anchor and refused to move for a day. Soon, Coast Guard officials came aboard the lobster boat.

Ward and O'Hara weren't arrested, but charges were filed for conspiracy and disturbing the peace.

Their case became a landmark moment for climate-change activists: Not only were the charges against Ward and O'Hara dropped, the Bristol County district attorney announced outside the courthouse that he agreed with Ward's action.

"Climate change is one of the gravest crises our planet has ever faced," Bristol County DA Sam Sutter said. "In my humble opinion, the political leadership on this issue is gravely lacking."

It's an event chronicled by Stephenson in his 2015 book, What We're Fighting for Now Is Each Other. He was at the courthouse that day. "It was truly one of the most head-slapping, jaw-dropping moments," he recalls.

Ward and O'Hara, after their 2013 charges were dropped, became founding members of the Climate Disobedience Center, which helps provide legal assistance to people engaging in acts of civil disobedience.

Those acts are increasing.

In Seattle, hordes of kayaktivists took to the waters of Elliott Bay in 2015 to delay an Arctic drilling station (Ward was there). Last spring, 52 protesters were arrested after sleeping on railroad tracks near Anacortes, Wash., to prevent coal trains from reaching refineries (Ward was there, too).

Most famously, in an act of dramatic protest, Greenpeace activists dangled from Portland's St. Johns Bridge in the summer of 2015 to prevent a Shell Oil icebreaking ship from heading to the Arctic.

As Greenpeace protesters were belaying off the St. John's Bridge, Ward was planning to block the ship himself.

He paddled out with a rowboat with the intention of anchoring himself in front of the ship, but was stopped by the Coast Guard.

Not everyone is impressed.

"People who break the law in the name of the environment usually have no real respect for the environment, and certainly none for the orderly processes that distinguish us from a mob," says Gordon Fulks, a physicist and climate-change denier who advises the Cascade Policy Institute—a Portland-based libertarian think tank.

Even mainstream environmental groups say they don't support the type of activism Ward engages in. "The Sierra Club currently has a long-standing policy against engaging in civil disobedience," writes Trey Pollard, national press secretary for the organization, in an email to WW.

But others say what Ward is doing is the future—the only way to take drastic climate-change action.

"We need to experiment with strategies that have the potential to be an exponential change, rather than the plodding along to the next steps," O'Hara says. "Ken recognized this earlier and more articulately than anybody else."

Anyone near the Trans Mountain pipeline Oct. 11 wouldn't have thought Ward was committing a crime. In his vest and hardhat, he looked the part of a maintenance worker. Cars passed on the nearby road without slowing as he snapped locks on two green valves inside the fence line.

As he broke the lock on one, a man fired up a leaf-blower close by. A dog barked from a backyard.

He silently turned an orange wheel on the pipe counterclockwise and locked it in place, sticking a bouquet of yellow sunflowers into the spokes and snapping a few selfies.

As Ward was turning the wheel, O'Hara was calling each of the pipeline companies to inform them of the group's pipeline shutdown.

"I'm calling to report that there are activists at a block valve site," O'Hara said into his cellphone. "We want to make sure you are aware of the situation so the pipeline can be shut down in a safe manner."

Ward fully expected to be arrested that day. But none of the valve turners knew what kind of penalties they'd face.

For sleeping on the railroad tracks in 2015, Ward faces a misdemeanor charge. He says that's typical for these sorts of protests. "But we figured that it might be stronger than that," he says.

Skagit County prosecutors instead charged Ward with three felonies. That's enough to send him to jail for the rest of his life. (The prosecutors declined to comment for this story.)

When Ward stands trial later this month, he plans to invoke something called a "necessity defense"—essentially, that he had no other choice but to break the law to prevent harm.

It's a defense that Ward's own attorney, Lauren Regan of Eugene, acknowledges rarely works.

"I've been doing this type of law for 19 years," she says. "I've gotten a necessity defense through [to trial] twice."

But if allowed, it could be effective, says Margie Paris, a University of Oregon law professor who specializes in criminal law. It's a strategy she says is sometimes referred to as "choice of evils." Self-defense cases—in which someone, for example, shoots and kills an attacker—often involve a necessity defense.

"Sometimes people are faced with a situation where it's better for them to break the law," Paris says.

In this case, Ward will argue that the government's actions are an attack on the planet, and he was acting in the earth's defense.

"The political system—which would be the legal way of taking action to avoid climate change—has proven itself to be unwilling or incapable of doing that," Paris explains.

So for a protester to say the government forced him to break the law? "It's a fascinating defense," she says.

It could be a legal strategy that becomes more commonly used by activists. John Foran, a University of California, Santa Barbara sociology professor who studies social movements, says he believes direct actions like Ward's, especially concerning climate change, will become more common under a Trump administration.

"[Trump is] going to do so many things that are almost surrealistically crazy," Foran says, "and sort of leading us over a precipice on climate, that that's going to speed up the coming to consciousness of lots of people. That's good."

While Foran believes more Ken Wards will emerge under Trump, protesting causes of all types, he says government crackdowns are also likely to increase.

"It just seems like it will be tougher across the board," Foran says. "Fewer permits to assemble, more police violence, tougher sentences for convictions, and on and on."

As he prepares to go to trial, Ward is also preparing to spend the rest of his life behind bars.

He spent the first days of 2017 at a silent meditation retreat. He's been making arrangements for his 16-year-old son, Eli, to be allowed to stay in their home and continue attending the same school.

He has wrestled with the question of whether the harm to his son—who may never again see his father outside a prison—outweighs the political stand he's taking.

"I feel like it is my boy's life, his future, that is at stake here," Ward says. "It was important that I be able to tell him that, whatever the outcome, I tried everything I could think of to do. I want to be able to say that to him."

Eli Ward says he respects his father's decision.

"He's trying to save the environment, therefore not have us die a horrible death," Eli says. "I'm proud of him for doing all that."

Ward believes others should join him.

Last week, Ward participated in a YouTube livestream. He spoke quietly, as always. But he said no protest march will be big enough to save the earth.

"If our major response to the Trump administration, which is in effect a fossil-fuel administration, is to put some people out with placards, I think Trump will laugh at that," Ward said. "We need to be doing things that fundamentally strike at the heart of what's killing us."