Editor’s note: This post was updated in July 2020 to remove formatting errors. None of the reporting has changed since 2015.

No elected official in Portland spends more time with constituents than Multnomah County Commissioner Loretta Smith.

Whether flipping pancakes at the Hollywood Senior Center or personally taking underprivileged teens from the SummerWorks program to buy office attire, Smith works her district nonstop.

“She’s really passionate about summer jobs for kids, and particularly for kids of color,” says Andrew McGough, executive director of Worksystems Inc., which partners with the county on summer internships.

And nobody on the top floor of Multnomah County headquarters is thinking harder about her political future than Smith.

Last fall, freshly re-elected to a second term, Smith sought the advice of County Attorney Jenny Madkour: Could the prohibition on county commissioners running for other offices midterm or the two-term limit for commissioners be overturned?

They could, Madkour told her, but other commissioners showed no interest in referring either question to voters.

Political consultants say Smith wanted to run for City Commissioner Amanda Fritz’s seat in 2016. After Fritz’s husband died in a September car crash, Fritz announced she’d run again after all, ending Smith’s hopes of running for a vacant seat.

Nonetheless, Smith , 50, continued to use her position to promote herself.

In February, she directed staff at county headquarters to spend $939 to book a flight to Portland for a man named Albert Turner Jr.

Turner, a county commissioner from Alabama, was scheduled to speak at a Feb. 27 Black History Month event at Living Room Theaters. Smith wanted taxpayers to pick up his travel expenses and $1,000 speaking fee.

But Smith’s order troubled county staff.

“The contract is very concerning,” a county finance officer, Patrick Williams, wrote in a Feb. 20 email. “We are to pay him $1,000, arrange a car service, provide security, and lodge him at a four-star or better hotel. Even if Commissioner Smith approves this, I don’t think it is allowable.”

Smith says the event was aimed at raising awareness of voting-rights issues.

Yet she accounted for the event as a political fundraiser to benefit herself. She spent $2,515 from her campaign funds to rent the theater. She listed the purpose as “fundraising expenses.”

It’s against state law to spend public money on an overtly political event that’s aimed at helping a politician raise money.

Turner didn’t make the trip because of a logistical snafu. But the event isn’t the only time Smith’s spending of taxpayer money has been aimed at elevating her political profile—and has alarmed county officials.

On 10 occasions in the past three years, county officials have required Smith to repay money she spent improperly.

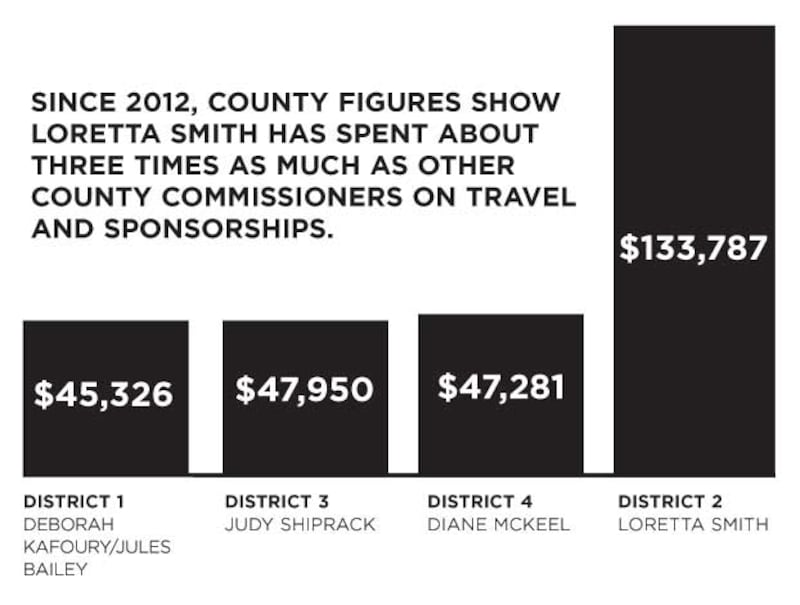

Records obtained by WW show Smith also spends more on travel than any of the other commissioners—$81,192 since 2012, nearly twice as much as the next most frequent flier. Smith often travels luxuriously—taxpayers, for instance, picked up a $420-a-night room for her in a San Diego hotel last June for a conference of Latino officials.

Since 2012, Smith has spent $52,595 in taxpayer money on nonprofit fundraisers—nearly as much as the other four county commissioners have spent combined.

County rules prohibit direct contributions to organizations, but buying tables at fundraisers and sponsoring events is allowed. Such expenditures raise Smith’s political profile in the community and earn points with voters. Smith’s expenditures appear to be legal; they also buy her goodwill from leaders of the organizations that Smith is spending taxpayer money to support.

“As an elected official, Commissioner Smith is ultimately accountable to her constituents,” says County Chairwoman Deborah Kafoury. “However, like all of us, she must appropriately manage her office’s use of county funds. As a principle, of course, county resources should not be spent to influence an election.” (Commissioners Jules Bailey, Diane McKeel and Judy Shiprack declined to comment).

Smith defends her spending. “I support programs that align with Multnomah County’s values,” she says. “I’m just doing what the constituents of District 2 want me to do.”

Smith, whose district covers North and Northeast Portland out to 185th Avenue, first won election in 2010. She’d spent the previous 23 years working for U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) in Multnomah County. One of her roles in Wyden’s office was handing out federal grant money.

“The folks in the community already knew me when I won this job,” says Smith.

In her first term, Smith rarely made news. But in June 2013, she became the focus of unwanted attention when Baruti Artharee, the police liaison for Mayor Charlie Hales, embarrassed her at public event.

“Here’s our beautiful commissioner, Loretta Smith. Mmm, mmm, mmm—she looks good tonight,” Artharee recalled saying to the audience. He claimed it was his way of giving her a compliment “in a comical way.” The incident, and public outrage, cost him his job.

Smith suffered a backlash among some African-American leaders for calling Artharee out. When she ran for re-election in 2014, Smith faced two candidates whom Artharee and his allies had encouraged to run. She won re-election by a wide margin anyway.

One of the ways Smith repaired relationships in the African-American community was to spend heavily on supporting local organizations.

Each county commissioner gets an annual office budget of about $560,000. Commissioners can use that money to hire staff, outfit their offices, travel and support community organizations.

In 2014, Smith spent $33,500 of taxpayer money on community organizations—more than the other commissioners combined, and nearly eight times what she had spent in 2013, when she wasn’t running for re-election.

Records show, for example, that Smith doled out $5,000 to sponsor an Urban League event, kicked in $3,500 to send members of the Peninsula Wrestling Club to a tournament, and paid $1,500 to help sponsor a graduation ceremony for Rosemary Anderson High School.

“The reason I do it is, it’s what the residents of my district want,” Smith says. “I get asked for money all day, every day.”

Smith says she always supports groups that advance the county’s mission of helping the underprivileged.

Except that’s not always the case. Last year, for instance, records show Smith spent $2,000 in Memphis, Tenn., to sponsor a youth program at the National Association of Black County Officials.

Smith declined to explain the Memphis sponsorship but says she’s careful to spend money for designated purposes. And yet, records show she spent $2,000 at grocery stores last year. She says those expenditures help needy constituents and that spending on food is appropriate for events that take place during meal times.

“I’m not doing this so people will support me,” she says. “I do it because this is who I am.”

In November, Kafoury ordered a revision of county policy on expenditures. The new policy prohibits “donations, contributions, unconditional gifts [and] grants.”

“When I took over as county chair, one of the first things I did was tighten up the standards regarding county spending, particularly around sponsorships, to ensure openness and transparency,” she says. “I will continue to look at ways to strengthen county spending policies so that we continue to meet the expectations of the public.”

In each of the past four years, Smith has spent more on travel than any other commissioner, including the chair.

Last year, Smith spent $26,750, far more than any other commissioner, visiting Atlanta, Washington, D.C., Memphis, and San Diego, among other cities, usually taking at least one staff member along and staying for several days at county expense. Her bill for four nights at the Coronado Island Resort and Spa near San Diego last June came to $1,900.30, not including food and her rental car.

County rules give commissioners wide latitude for travel. Smith’s chief of staff, Barbara Willer, says Smith’s trips benefit her constituents.

“Commissioner Smith is in leadership positions on boards that serve Multnomah County’s interests,” Willer says. “These boards are both local and national in scope and require her to travel.”

More than any other commissioner, Smith has run afoul of county spending guidelines.

Over the past year, county finance officials have asked Smith to repay taxpayers for her spending on 10 occasions, totaling $1,700.

Most of the repayments are for improper expenditures totaling about $1,400. The biggest single repayment was for $500, when Smith took out duplicate cash expenditures for a 2013 trip to Washington, D.C.

Last year, Smith spent $250 of county money on a campaign photo shoot. On that occasion and two others, Jimmy Brown, one of five chiefs of staff she’s had in the past four years, paid money back to the county. In one instance last July, Brown paid Smith’s $47.55 in arrears to the county when her check for a disallowed bar tab in Washington bounced. Smith says she accidentally wrote a check on an account she had closed out of concern about identify theft.

Smith says in the other cases that Brown paid the county back on her behalf as she was traveling, and county officials OK’d it.

“What we’re talking about here is mostly trip reconciliations,” Smith says. “If you’re asking if I’ve done anything inappropriate, the answer is no.”

Kafoury wants commissioners to be above reproach.

“I have spoken with every board member about appropriate county spending,” Kafoury says.”I believe our job at Multnomah County is to stretch every dollar so that we can continue to provide critical services to those in need. That always has to be our top priority.”

WWeek 2015