Every day, Craig Williams walks through the wards at Oregon Health &

Science University hospital asking patients why they were admitted.

More frequently than ever before, says Williams, a professor at the Oregon State University-OHSU School of Pharmacy, patients tell him they are diabetics who have experienced complications. That's because they've either rationed their insulin, they say, or stopped taking it altogether.

"When you ask why," says Williams, "it's cost."

His observations are confirmed by state figures, which show the incidence of people being hospitalized because of complications from diabetes is up 23 percent over the past decade.

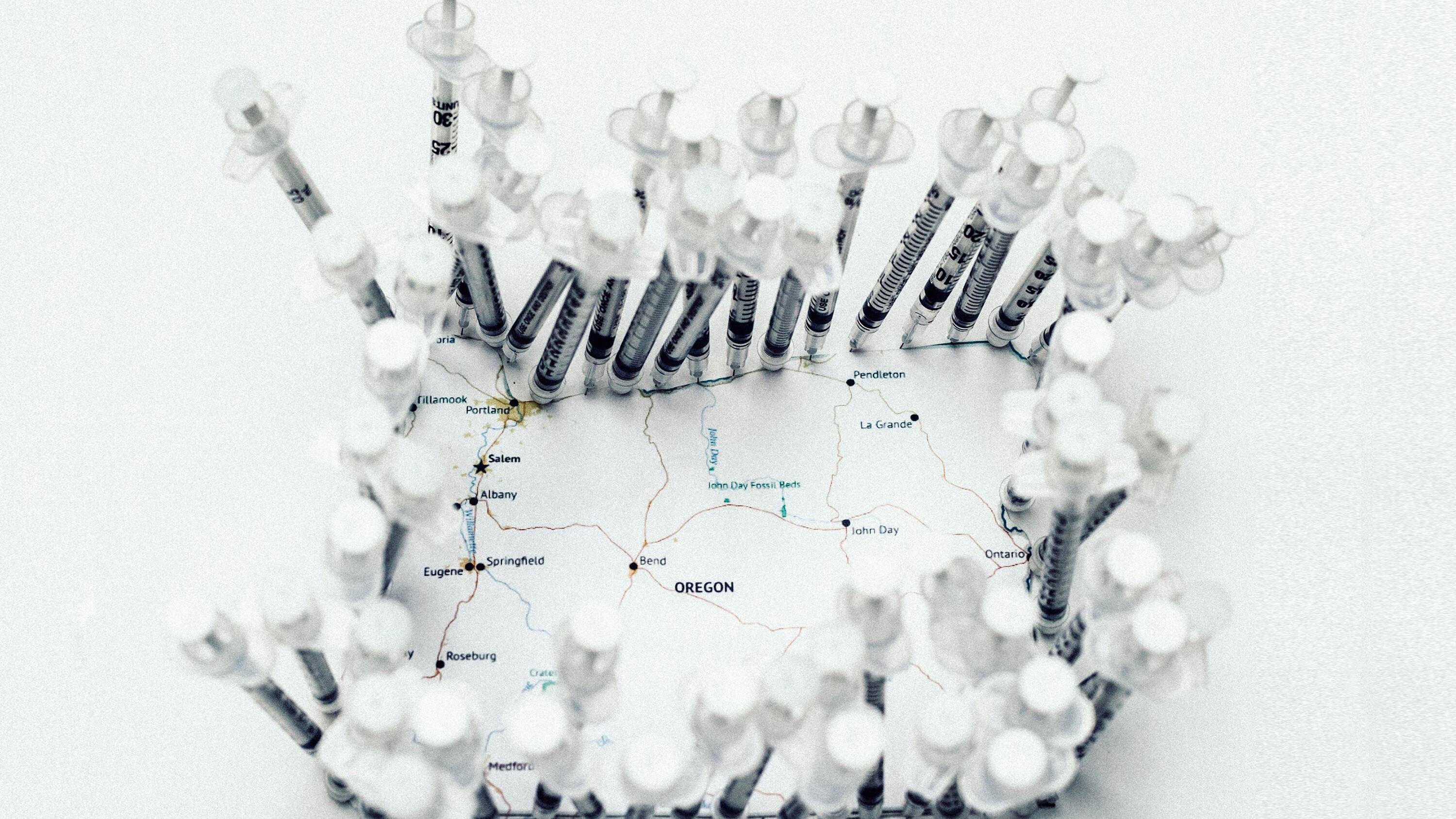

The high price of insulin is an issue in every state, but it's a particular problem in Oregon. Nearly 1 in 10 Oregonians suffer from diabetes, a rate well above the national average. Without daily doses of insulin, many would die.

That's in part because insulin is so expensive. U.S. list prices have risen 500 percent over the past decade.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, total spending on diabetes is $100 billion a year nationally. Most of that goes to insulin.

That's not because insulin is a high-tech wonder drug. Experts say the insulin formulations made by Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Eli Lilly—the three companies that dominate the global insulin trade—have changed relatively little since the turn of the 21st century.

"It's basically the same drug with some modifications," says Dr. Andrew Ahmann, a diabetes specialist at OHSU. The increase in the cost, he says, "makes no sense."

Ahmann, who's been researching and treating diabetes for 30 years, says U.S. insulin prices, which are four times higher than prices in other developed countries, are an enduring mystery.

Two Oregonians say they have solved the puzzle.

Three years ago, Julia Boss and Charles Fournier became outraged at the cost of insulin for their daughter Genevieve, then 8. So they did something about it: They started a nonprofit, the Type 1 Diabetes Defense Foundation, turned their Eugene home into a war room, and set about decoding the complex supply chain between drug makers and diabetes patients.

Their conclusion: The culprit is a hefty, secret rebate that drug makers pay to middlemen—mostly health insurance companies—who obtain insulin for patients.

In 2017, Boss and Fournier filed a lawsuit against the manufacturers and those insurers, alleging they were conspiring to artificially inflate insulin prices. (The case is pending.) More recently, they have turned on state regulators, like the Oregon Insurance Division, arguing the agency has not done its job.

"Protecting the public from being overcharged is Insurance Regulation 101," Fournier says. "And Oregon's insurance commissioners aren't even close to earning a passing grade."

The result? Un- and under-insured Oregonians with diabetes are paying exorbitant out-of-pocket costs.

A recent email exchange between Fournier and Oregon Insurance Commissioner Andrew Stolfi captured the intensity of the issue. When Fournier criticized Stolfi's agency, which sets health insurance rates, Stolfi complained about his tone.

"My tone is not the issue that should be concerning you," Fournier replied to Stolfi in an Oct. 19 email. "People are dying and going bankrupt—or incurring life-threatening medical complications as they ration insulin."

People like Sandra Cook.

Not everybody pays sky-high prices for insulin: Public employees and private workers with high-end insurance plans get a vastly better deal. But the growing number of people who lack Cadillac insurance coverage face crippling out-of-pocket costs that force them to use less insulin than they need or go without. Doctors and patients say either can have catastrophic consequences.

Sandra Cook, 34, and her daughter, Emma, 11, both suffer from type 1 diabetes.

Cook, 34, a single mom who lives in Bend, has had diabetes for three decades. Three years ago, Cook, had insurance through her employer, but it came with a $2,500 per person deductible.

That meant she had to pay cash for insulin for both her and her daughter for several months before her insurance began paying.

She couldn't afford it.

"I rationed my insulin," says Cook, who lives in Bend. "I was taking only half of what I needed and giving the rest to Emma. It was depressing and made me feel like crap physically and mentally. I ended up in the hospital for three days."

Cook says she has friends in a diabetes support group who've gone without, shared insulin and used expired products.

OHSU's Ahmann says that's consistent with his experience. "We see a lot of patients who ration their insulin," he says. "And we see lots of people who are spending a disproportionate amount of their incomes."

Cook's daughter, Emma, a Girl Scout, is now on her father's insurance (her parents don't live together). Cook says that insurance creates hardships, because it only works with certain pharmacies. So she either has to drive the 120 miles to Springfield to pick up Emma's insulin with a $160 a month co-pay or pay $1,400 a month out of pocket in Bend.

"It sucks," Cook says. "Trying to pay to keep myself and my daughter alive is exhausting."

Over the past decade, the number of Americans with high-deductible health insurance has tripled to about 45 percent, according to federal figures. Another 10 percent have no health insurance at all (the uninsured rate is lower in Oregon, about 6 percent).

Patients with high-deductible plans pay for insulin based on manufacturers' list prices—which are well above what the insurance company pays.

Mike Snaadt, 47, who owns the Helen Bernhard Bakery on Northeast Broadway, has one of those high-deductible plans.

Snaadt's daughter, Clarissa, 14, often helps out at the family business, where she'll sample her favorite treats: a lemon bar or lemon Danish. But she suffers from type 1 diabetes and has to monitor her diet carefully.

"Clarissa doesn't know life without diabetes," says Snaadt. "She's really good at math—because she's been doing fractions since she was 4, figuring out what she can eat."

Snaadt used to work for a multinational company, whose generous health insurance plan made Clarissa's insulin virtually free. Now, as a small business owner, he pays $20,000 a year for health insurance for his family of four—and another $250 in cash each month for three vials of insulin.

Part of the reason he pays so much out of pocket is that as the holder of a high-deductible insurance policy, his price is based on the insulin manufacturers' list price. He gets no cost reduction from the rebates manufacturers pay the middlemen, including Snaadt's insurance provider.

Car makers regularly provide discounts to dealers in the form of factory rebates. So do the food companies whose discounts and rebates lure shoppers to crowded grocery aisles. In those situations, rebates are passed on to customers in the form of lower prices.

Not so with insulin.

Insulin makers do provide incentives. They pay massive discounts to middlemen, companies called pharmacy benefit managers that pass most of the rebates along to insurance companies. Fournier and Boss discovered those rebates can approach 70 percent of the list price: $200 on a $300 vial of insulin.

But Snaadt and other insulin buyers with high-deductible insurance don't get the benefit of the discounts drug companies rebate to middlemen because the middlemen keep the money.

The precise details of the rebates drug companies pay to middlemen are a closely guarded industry secret, kept confidential by law.

"Part of the problem here is that rebates are almost completely opaque," says Dr. John Santa, a longtime public health physician who serves on the Oregon Legislature's Fair Pricing of Prescription Drugs Task Force.

But using drug companies' financial filings with the federal Securities and Exchange Commission, professor Neeraj Sood, a health economist at the University of Southern California, calculated the gross value of the rebates and who gets them.

Sood presented his findings to the Legislature's drug pricing task force in August, showing that the value of rebates accrues mostly to the health insurers.

Sood highlighted insulin in his research, noting two additional characteristics that penalize people with diabetes: Manufacturers increase their prices regularly and in lockstep, and the rebates they pay middlemen have grown dramatically over the past decade.

Pharmaceutical companies pay rebates on only about 3.5 percent of drugs. Of those drugs, insulin is the most widely prescribed.

That's why Fournier and Boss have gone to war.

In his day job, Fournier, 48, a tightly wired Frenchman, pulls apart large construction contracts to make sure every penny is accounted for. A Yale-trained historian, Boss, 51, earns her living editing and translating scholarly publications.

After figuring out that middlemen were pocketing the rebates that could lower their and many other families' health care costs, the couple decided to take action.

They contacted Keller Rohrbach, a plaintiffs' law firm that often pursues class action lawsuits. In March 2017, the firm filed a federal lawsuit in New Jersey, where many of the drug companies, pharmacy benefit managers and insurers are headquartered. They alleged drug makers and middlemen were conspiring to artificially inflate the cost of insulin to patients. Boss was the lead plaintiff.

Although the couple have since split with the law firm, the litigation is grinding on. The state of Minnesota filed a lawsuit against insulin manufacturers, but not insurers, last month. (No other state has joined it.)

In the meantime, Sood, the USC economist, told Oregon's fair pricing task force members that the state ought to fix the problem itself.

Sood advised lawmakers to "mandate the pass-through of discounts to consumers," in order to "ensure that consumers get the benefits of rebates."

"Dr. Sood made the common-sense argument that cost for all prescription drugs is net cost. You start with the list price, you subtract anticipated rebates and other offsets, and you base the payments on the resulting net cost," Boss says. "Dr. Sood told the task force the current practice of rebate capture was extremely unfair—he called it 'a tax on the sick.'"

But as Boss and Fournier learned, it's not enough for an idea to make economic sense. It's also got to pass political muster, and given the realities of who the players are in Salem, that's not easy.

Perched in a 24th-story conference room with a stunning view of the West Hills sits Moda Health's pharmacy director, Robert Judge. With his starched white shirt and neatly trimmed beard, Judge appears typecast for the role of corporate overlord whose only interest in insulin lies in maximizing his company's profits from the drug.

But Judge, 58, also suffers from type 1 diabetes.

When he was diagnosed in 1988, he was an ultra-marathoner, competing in 100-mile races. He's also keenly aware of how the price of insulin has increased. Thirty years ago, Judge says he paid $12 a vial for Humalin, a brand of insulin manufactured by Eli Lilly. Today, he says, a vial of Humalin costs $700.

"It makes you shake your head," Judge says. "I hear the argument that bringing a new product to market is expensive for the drug companies because of research costs—but it's the same product."

Judge is also part of the Oregon legislative task force looking at drug pricing. At its Oct. 25 meeting, the group discussed using rebates to lower costs for the patients. Judge panned the idea.

He acknowledges Moda receives rebates from drug manufacturers. He also acknowledges that insulin rebates have grown substantially in recent years.

But he says the approach Fournier, Boss and Sood, the USC professor, propose—passing the value of insulin rebates along directly to diabetes patients—is a bad idea.

"From an insurance perspective, that's not good policy," he says.

Judge says it make more sense to continue to treat the rebates as general revenue for insurers and put that revenue into a communal pot to lower costs for all customers.

That infuriates Julia Boss.

In effect, she says, Moda is using her daughter's life-threatening auto-immune illness to subsidize the monthly premiums of healthy people who get their insurance from the same company her family does.

"That's not how insurance is supposed to work," Boss says. "Insurers are supposed to spread real costs over the entire risk pool. They're not supposed to make a sick person pay fake costs for treatment because they've decided that sounds like a good deal for the healthy. That's the definition of discrimination, not the definition of insurance."

In addition to pursuing national litigation, Fournier and Boss hoped they could get help in Salem from the Oregon Legislature and the Oregon Insurance Division, which regulates insurers' rates.

But when it comes to insulin, they've found powerful interests are content with the status quo.

In 2017, a coalition called Oregonians for Affordable Drug Prices Now (later renamed The Oregon Coalition for Affordable Prescriptions) did push

to limit drug prices, but that group focused on a broad range of drugs rather than just insulin.

The coalition represented public employees, whose health insurance provides free insulin, and health insurers, who have no incentive to give up the rebates they currently capture.

Fournier says that's part of the reason solutions to the problems of people with

diabetes and no or high-deductible insurance don't get much traction in Salem.

"Free insulin [for public employees] insulates state employees, including legislators, from the slow-moving health care catastrophe they are creating for the rest of us," he says.

The coalition sponsored a bill in the 2017 session that would have required drug manufacturers to offer prices in Oregon pegged to prices in other countries. (Many other countries' drug prices are significantly lower than the U.S.'s, because they have single-payer systems that grant them greater bargaining power.)

The lobbying group for drug makers, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, killed that bill. The industry has successfully lobbied against states' efforts to control drug prices, and sued when necessary, arguing that price controls violate federal laws. (PhRMA declined interview requests.)

The legislative task force considered last month whether to recommend that Oregon require at least 50 percent of the value of drug rebates to be passed on to patients, but it decided against doing so.

State Sen. Elizabeth Steiner Hayward (D-Portland), the senior lawmaker on the legislative task force, says she's aware of Boss and Fournier's concerns. But she says the task force focused on the entire supply chain for prescription drugs, not any single part of it.

"The whole point is to create more transparency throughout," Steiner Hayward says. "We are not inclined to play favorites or create scapegoats."

Earlier this year, United Healthcare, the nation's largest provider of health insurance and one of the defendants named in Fournier and Boss' lawsuit, reacted to growing pressure and announced it would stop pocketing rebates that could benefit 6 or 7 million of its customers.

United is a relatively small player in Oregon, and there's no indication Oregon insurers such as Moda will follow United's lead—or that lawmakers or state regulators will put pressure on them to do so.

Fournier and Boss have asked the insurance commissioner to investigate the rebate system. Stolfi, who was unavailable for comment, did open such an investigation last month, although it's too early to say whether it will yield any results.

Mike Snaadt hopes such efforts will reduce the role of middlemen. He sees the customers of his bakery every day face to face. He wants the same system for the live-saving drugs his daughter needs.

"It's a flawed system that is definitely rigged for the benefit of people who aren't adding value," Snaadt says of the insulin market. "I wish drug companies distributed directly to us through Amazon."

Sugar and Blood

Diabetes kills more Americans each year than breast cancer and HIV/AIDS combined.

Oregonians have a high rate of diabetes: 9.6 percent of the state's 4.2 million people suffer from the disease. That's a rate significantly higher than in Washington state (7.7 percent) and the national average (8.7 percent). As many as 1.1 million people in Oregon may have prediabetes, according to state figures, which means they are likely to acquire the disease if they don't change their habits.

Diabetes occurs when the pancreas fails to produce enough insulin, a hormone

that regulates blood sugar. The human body turns carbohydrates into glucose, a sugar that powers the brain and body.

If blood sugar falls too low, the body begins burning fat and essentially poisons itself, which can lead to coma and other complications. If blood sugar rises too high, dizziness, blurred vision and nausea can result. The long-term impacts include blindness, circulation disorders leading to amputation, kidney failure and premature death.

Most people with diabetes—about 95 percent—have type 2, which is associated with obesity. The disease strikes men more than women and hits Latinos, Native Americans and blacks particularly hard. They are three times as likely as whites to have the disease.

Type 1 diabetes, sometimes called juvenile diabetes, is caused by an autoimmune disorder in which the body attacks and damages the pancreas. It accounts for about 5 percent of people with the disease. (Chris Dudley, the former Portland Trail Blazer who ran for Oregon governor in 2010, is a prominent type 1 diabetic.)

The nonprofit WW Fund for Investigative Journalism provided support for this story.