Every winter, Gary Sargent worries a flood could put him out of business.

Since 1988, Sargent has owned Sargent's MotorSports, a motorcycle shop on Southeast Foster Road at 102nd Avenue, just off of Interstate 205. He says flooding has gradually worsened in the decades he's owned the property. In 2015, an overflowing Johnson Creek submerged Sargent's shop under 4 feet of water. He's still working to make back the $50,000-plus in damages the flood cost him.

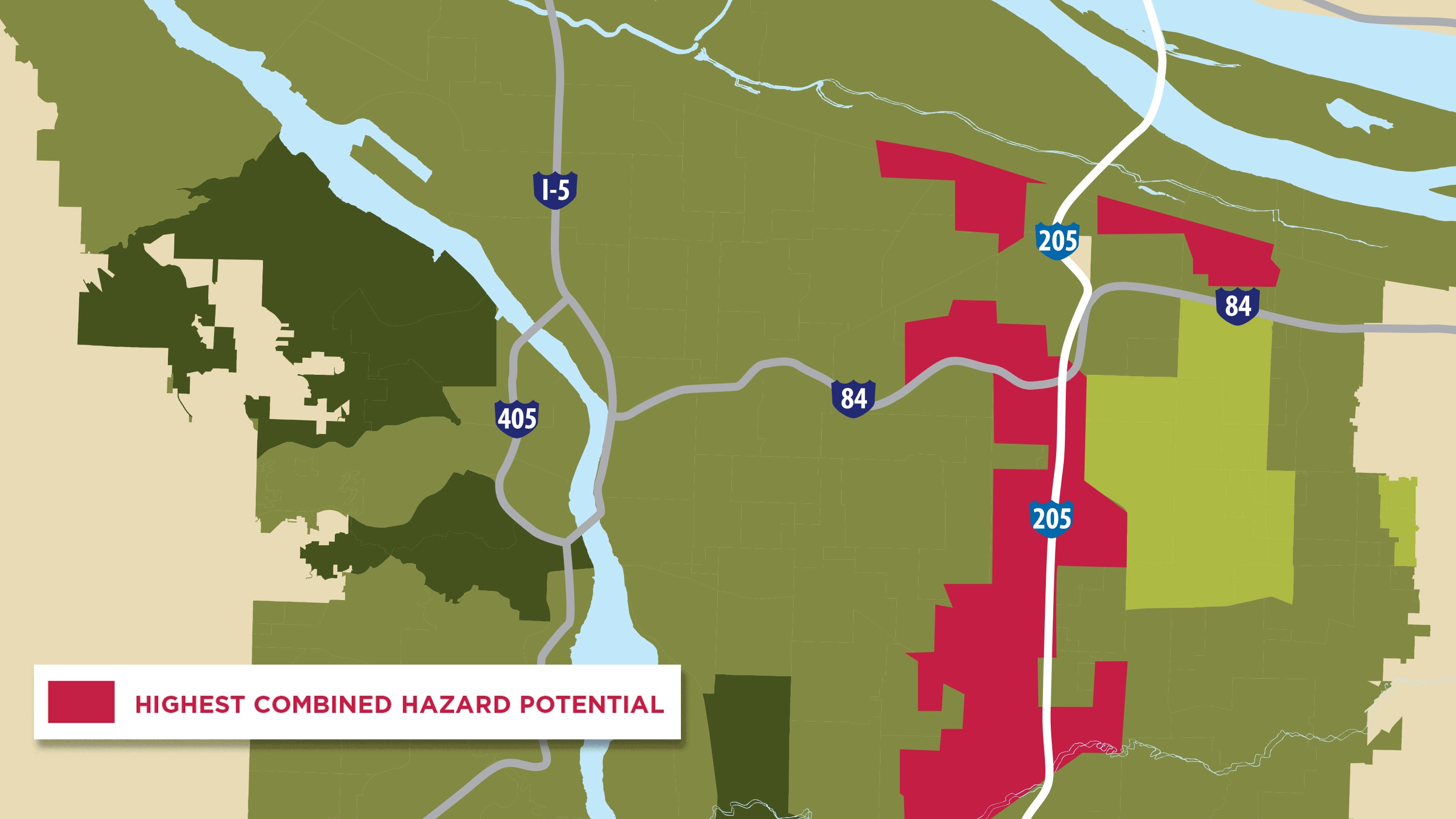

Sargent isn't alone. As weather in Portland becomes more extreme, residents who live on the eastside along the I-205 corridor are the most likely to be impacted by increasing environmental hazards.

That's among the findings of a Portland State University study released last week. It tracks gentrification and climate change to map out which parts of the city will be hit hardest by flooding and extreme heat.

"Historically, redistricting policies and class-based segregation have led to largely uneven risks for environmental disasters," the study reads. "Areas most affected by climate-induced risks frequently contain marginalized populations, such as non-white, low-income, and persons with economic hardships."

It notes that as temperatures warm, winter snowfall changes to rain. Wetter winters and drier summers will affect areas like East Portland most—where there is less vegetation, more traffic, and fewer trees and investments in green infrastructure. As rising costs push people to the edge of Portland, residents here are increasingly low-income, minorities or immigrants.

Heejun Chang, chairman of PSU's geography department and the study's co-author, says the I-205 corridor is particularly vulnerable in winter because it sits at a lower elevation and its drainage systems can't accommodate heavy rainfall. The area is also an urban heat island—meaning it absorbs heat during the day and releases it in the evening after the sun sets. (Think of the parking lots of Mall 205, which turn to ponds in the rainy months but bake like an asphalt Sahara each summer.)

Related: It Really Is Hotter in East Portland, By About 20 Degrees

Chang says the city is using the study to help inform infrastructure planning, but that it could do more to address the socio-demographic factors that put eastside residents at greater risk.

"The city can do better in education and outreach to those populations who are not aware of flood risks and might not speak English," Chang says. "[It] needs to prepare for changes in climate and understand the changing geography of the area."