For more than a year, Oregonians have been waiting for the end of the pandemic. For 226,999 of them, the end began here.

The Oregon Convention Center—a cavernous, 160,000-square-foot hall plopped in the no man’s land between Moda Center and the industrial eastside—hosts the state’s largest vaccine clinic.

Every hour it’s open 1,100 Oregonians walk through a maze of queues. Awaiting them: A needle filled with Pfizer or Moderna.

More than 1 of every 8 COVID-19 vaccine doses in Oregon have been administered here, in a space that’s three-and-a-half football fields’ worth of rope lines, chairs and volunteers.

What’s it like? It’s a logistical masterpiece—a medical Disneyland. Yet it also feels as spare and anxious as the line for customs at an international airport.

“It was way more efficient than customs,” says Elliot Rask, 25, a commercial real estate broker, who clocked his walk at 960 steps during his April 22 visit. “Way more spacious, way more employees, you keep moving. It was kind of like the best airport in the world maybe. But no food and no one was tan.”

The ceiling shines with brightly lit squares of fluorescent light, like a cross between a sci-fi starship and a Walmart. The hum of human voices vibrates off the concrete floor.

And for those arriving after a year of avoiding crowds, the first step indoors can be arresting.

“I had a little pang—I wouldn’t say terror—but it was a little bit like, whoa. I know this is supposed to be like exciting and safe, but I’m a little freaked out,” says Mark Brenner, 51, a University of Oregon professor who lives in Southeast Portland and received his second shot April 21.

But what also stands out is the speed of the process. The lines move quickly, by design. The operation is a conveyor belt of arms being marched to the shots.

“It’s like a fucking Swiss watch,” says one patient who went through this week, “churning that many bodies through.”

The timepiece analogy doesn’t capture the mood of the place: It’s celebratory. On a recent Sunday morning, staff and volunteers applauded as they opened the registration desk at 11:45 am.

“It’s awesome to be a part of history,” says Laurelei Bailey, a pediatric nurse who administers shots. “I’ve never worked in a place for so long that everybody wants to be there every day. Not just the people who are working there, but people who are coming.”

Part of the pleasure? After a year in which nearly every American institution buckled under pressure, this works. It’s refreshing to see efficiency and competence in an undertaking of this scale.

Portland’s four hospital systems linked arms to mount an unprecedented operation—All4Oregon, they call themselves—to get the city and its suburbs vaccinated.

But since the new year, the only people who’ve been inside are those with an appointment and the volunteers and staff to help administer the shots. Reporters and cameras are generally barred.

WW spent the past two weeks hearing the experiences of the people who visited, learning the mechanics that made it possible, and meeting a few of the people who keep it running.

Now, we can offer you a virtual trip inside.

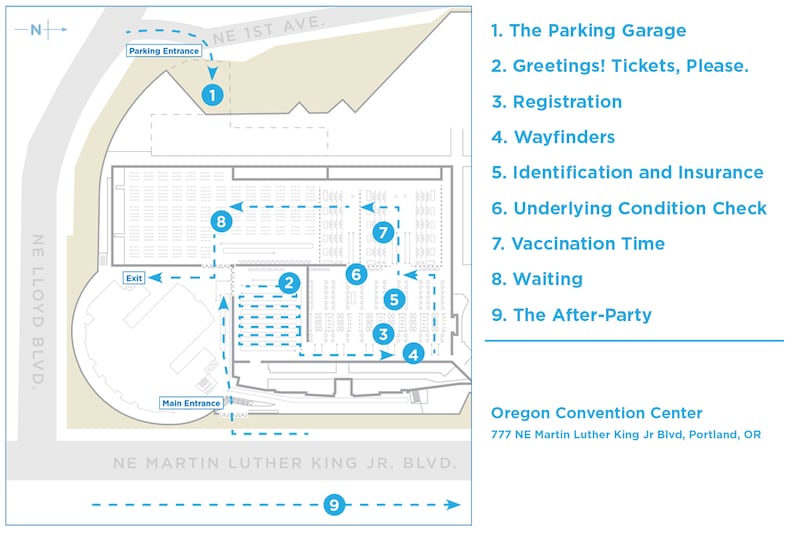

1. The Parking Garage

There are 850 parking spaces under the Oregon Convention Center. Other than the number of available doses (see “How the Vaccine Gets to Your Arm” page 15), this is the primary limitation on how many people at a time can be vaccinated here.

That’s a key reason why site operators are trying to shave off every minute upstairs: The goal is to get everyone back to their parking spot in 40 minutes. That rate of turnover leaves space for almost everyone to arrive by car.

At bad moments, the basement garage can become a traffic jam. Honking horns echo across the support pillars as people—sometimes elderly and in wheelchairs—weave between idling cars toward the elevators. Parking attendants often work double duty as crossing guards—halting traffic and trying to stop people from crawling on all fours to attempt shortcuts under barriers.

The anticipation messes with visitors’ minds. “I had one person tell me, ‘I was so excited to come today I didn’t remember where I parked.’ They literally don’t pay attention,” one attendant says with a laugh.

2. Greetings! Tickets, Please.

As people arrive by elevator or stairs in the Convention Center’s carpeted lobby, the first thing they see is a man dancing to a portable radio.

“It was just this dude. He was just kind of dancing around,” recalls Vince Jamie, 34. “They were playing ‘In the Air Tonight’ by Phil Collins.”

Behind the dancing usher: a rope line to enter Convention Hall D, where the vaccinators are. Workers at the door ask to see a QR code or a confirmation email—a bit like getting your ticket checked to enter a Blazers game.

The vaccination site is by appointment only. Just 3% of people don’t show for their appointment.

The bigger problem? “The major holdups that will slow down their entire machine is patients that arrive on the wrong day or don’t have an appointment,” says Chris Markesino, operations chief of the OCC site. “When patients arrive either on the wrong day or without appointment, we have to be able to pull them out of line quickly—so we don’t stop the entire line.”

In addition to running the OCC site, Markesino is regional emergency management director for Kaiser Permanente. He choreographs the vaccination ballet, pacing some 20,000 steps during his 12-hour days, crisscrossing the operation in black Merrell dress shoes. He wears a white vest marked “CHIEF.”

Markesino returned from a yearlong National Guard deployment peacekeeping in Kosovo just before Christmas 2020.

He grew up in Portland and returned home to be a part of history.

He quotes World War II Gen. Omar Bradley in the Sunday morning meeting with the team leaders who have managed 1,659 volunteers. “‘Amateurs talk strategy. Professionals talk logistics,’” Markesino tells them. “This is a big operation. It takes a lot of us to make this happen.”

3. Registration

Once an usher confirms you have arrived on the correct day, you are directed into a vast, twisting queue in Exhibit Hall D.

Up to 250 people can fit in this first space. Arrows on the floor offer direction; 2,000 dots applied to concrete floors throughout the OCC remind people to socially distance.

Markesino has 400 stanchions on hand, each with 7½ feet of retractable belt, for up to 3,000 feet of barrier, like what you’d expect for a roller coaster.

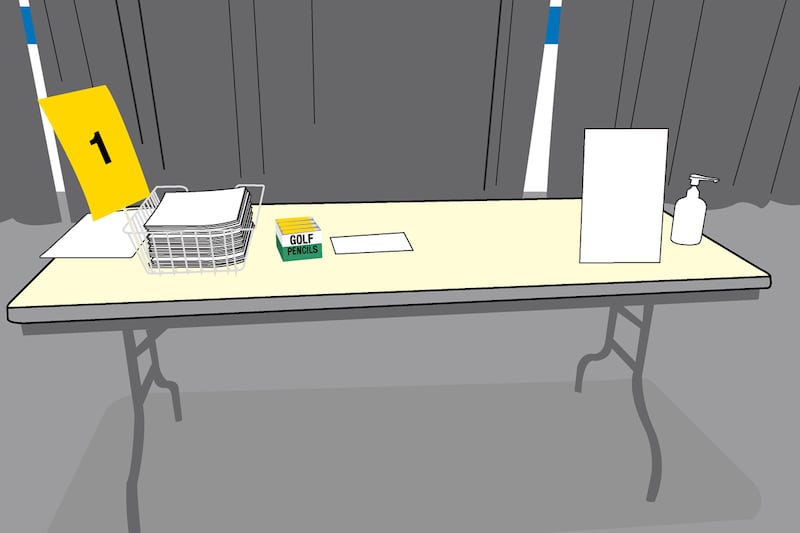

At the end of the line, a yellow-vested gatekeeper directs people to one of 24 check-in desks for 30-second interactions.

At that desk, staff ask patients for a COVID-19 check (“Have you had any symptoms? A recent diagnosis?”) and hands them a registration form and a golf pencil.

People fill out the form at their own pace, at round tables that look like they’d hold cocktail glasses at a low-budget wedding reception. That’s another way to speed the operation: Whoever fills out paperwork fastest can move ahead.

But consider that golf pencil. It’s an ordinary item, but it reveals the level of detail considered in the large operation.

“We bought up all the golf pencils in the tri-county area,” says Markesino. And they are reusing them.

“We’re running low on buying golf pencils, [partly] because they’re not making very many during the pandemic,” says Markesino. “So our volunteers actually wash pencils, to be able to put them back into circulation.”

How do you wash a golf pencil? An army of volunteers wipes them down with hospital-grade sanitary wipes.

4. Wayfinders

A platoon of helpers wanders through the throng of people waiting in line and filling out cards. “Wayfinders,” Markesino calls them.

They remind visitors to get out their ID and insurance cards before the registration station, and to take off extra layers before arriving at the vaccination chair. Their instructions give patients a sense of orientation so they aren’t surprised or unprepared for the next stage. It’s speed with a human touch.

Virginia Kincaid is one of the volunteers. Wearing a yellow vest, face shield and surgical mask, she is stationed near the exit.

Gregarious at 78 years old, Kincaid moved to Tigard nine years ago from Texas for her grandchildren. She came to volunteer at the Convention Center to “give back” after receiving her vaccine here a few weeks ago.

Her only hesitation? Driving into Portland.

“I mustered my courage,” she says. “I’m really nervous about driving in Portland, because pedestrians will step out right in front of you. I’ll drive around Houston with my eyes closed. I did a dry run to find this place. Easy-peasy.”

Before the pandemic, Kincaid volunteered at Randall Children’s Hospital to cuddle babies in the neonatal ICU and serve lunch to seniors younger than she. Kincaid spent her year at home relearning to play the piano after a 35-year hiatus, but she was eager to return to volunteering.

Kincaid stops people to make sure they’ve completed their paperwork fully before they step through the next doorway.

One woman she stops on a recent morning wears a black mask with a message about the pandemic: “This was preventable.” Kincaid compliments her on her mask and agrees: “It was.”

5. Identification and Insurance

For most patients, the last step before a shot is another table that confirms their insurance has been entered into the computer. As in a doctor’s office, staff checks ID to match the patient with the appointment.

That function is often performed by the National Guard, which is among the many agencies called into service at the site.

That presents a hurdle for some.

For all its efficiency, the OCC faces several criticisms. The place is massive—and while it has wheelchairs at the ready, it’s a lot of walking for seniors and people with disabilities. Also, it’s pretty much English only, say Latinx leaders.

And for undocumented immigrants, having their ID and insurance handled by soldiers in uniform isn’t exactly welcoming.

“It’s one of the barriers that has effectively moved us to not consider this a viable site for further investment of time and energy,” says Tony DeFalco, executive director of Latino Network.

(OCC organizers say they’ve tried to make the site more welcoming; that effort includes a Spanish-language registration desk. Meanwhile, Legacy Health runs a Latinx-focused immunization drive in Woodburn; Oregon Health & Science University runs a drive-thru clinic at Portland International Airport that started by exclusively serving mobility-impaired patients.)

If you don’t have ID, there are other security questions to prove the appointment is yours. If you don’t have proof of insurance, the guard member shrugs and moves you along for a shot anyway. Vaccinations are free.

6. Underlying Condition Check

The anticipation now reaches its height. Once you’re clear of registration, it’s time to line up for a shot.

“That was probably what I noted was just the longest wait,” says Kathy Wai, a North Clackamas School Board member. “I want to say around five minutes. It was a huge line. It just kept growing. But I was always taking steps.”

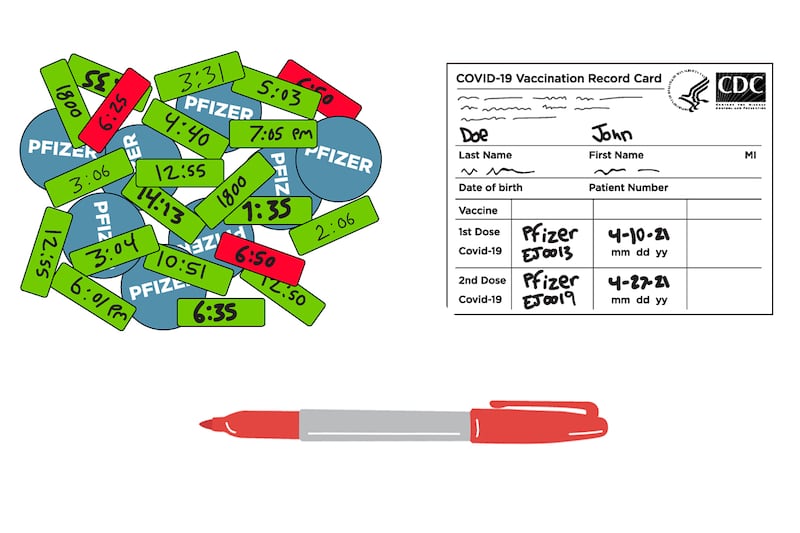

For some, there’s no wait depending on the time. For others, the wait is longer. That’s because, when filling out their forms, they mentioned an underlying condition or an allergy. National Guard members circle potential problems with a red felt-tip pen. Red marks on your paper? You get diverted to a row of tables where a medical professional evaluates your risk of side effects. If approved, you rejoin the queue for vaccines.

7. Vaccination Time

Needles go into arms at 100 vaccination stations. The vaccinators include retired doctors, EMTs and nursing students. Each desk is supplied with dose vials, hypodermic needles and adhesive bandages.

National Guard member Sanoe Aina has been vaccinating hundreds of people a day since January.

“Everybody I’ve seen has been overly grateful,” she says. “People can thank me about 10 times in the two minutes they’re in the chair. “I always joke: I’ve never seen people so excited to get a shot.”

A small fraction of people arrive at the station and—at the last possible moment—have second thoughts about the shot. In those instances, a vaccinator can wave a pink laminated 8-by-11 card. A nurse comes for a visit to answer any questions.

Related: How the vaccine gets to your arm.

The vaccine stations are set up for efficiency. As at the registration desk, there’s a yellow paddle with the station number to alert a volunteer to send the next patient. A blue card signals for more vaccine supplies.

Amid the tables, there’s a curtained-off area, nicknamed the “Zen den,” for people who forgot to wear a short-sleeved shirt, are suffering anxiety, or otherwise need privacy.

For the last two hours of the day, the Convention Center operation slows slightly. Vaccines are mixed and put into syringes on demand so as to avoid waste.

“They’re [going through] with a literal clicker, seeing how many people are actually in the center so they don’t make the mistake of having excess vaccines and wasting vaccines,” says Aina.

Laurelei Bailey, the pediatric nurse, was struck by the artwork on the shoulders she vaccinated. “I’ve seen so many tattoos,” she says. She stuck a needle into Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince and Pablo Picasso’s The Old Guitarist.

The patients cry with relief—and sometimes the nurses spend time trying not to.

“I fight back the tears,” says Angela Dorman, a registered nurse. “I just had a patient earlier [today] who lost her mom to COVID. She cried when she got her injection. You have moments like that with people, and you have moments where people are like, ‘I just want to get my injection so I can hug my grandchild for the first time in a year.’”

Dorman, who wears big lab goggles with pink rims, works nine hour shifts vaccinating people. On a recent afternoon, she sat outside the Convention Center eating a steak Thai salad provided by her bosses. She had a story for every bite.

“I had a person whose wife was in labor, and I asked, ‘You’re here. Why?’ and he said, ‘Before I hold my baby for the first time, I want to know that I’m vaccinated, even if by a few hours.’”

8. Waiting

As they leave a station, patients get a white Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccination card. The last thing the vaccinator does? Affix a piece of colored tape to the lapel of the newly vaccinated person.

The tape—in most cases a Seahawks neon green—is marked with the time that person can leave the Oregon Convention Center. It’s usually 15 minutes after their dose.

People with allergies or underlying conditions get pink tape. It lists a wait time of 30 minutes after their dose.

The stickers are a safety protocol developed after instances of allergic reactions. (There are other safeguards: An infirmary lies behind a curtain in case of a slip-and-fall or any kind of medical event.)

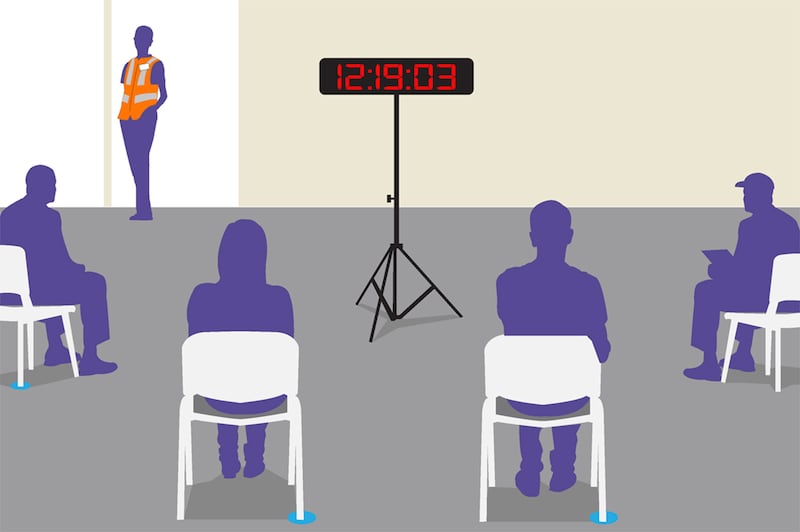

In the waiting areas, 650 chairs are spaced 6 feet apart. Some chairs are grouped in pairs for couples.

People receiving first or second doses are sent to different waiting areas. The first-dose patients sit closer to the desks where they can book a second-dose appointment. Schedulers with computers on wheels (COWs for short) also come to people where they sit—like flight attendants pushing beverage carts down airplane aisles.

There’s a hushed feel in this space. Newly vaccinated people sit with their thoughts, or look at their phones, waiting to return to the world. Volunteers hand out water bottles and watch for poor reactions.

“There wasn’t socializing,” says Dianna Parrish, 36, who was vaccinated April 22. She alarmed the side-effect monitor by sporting a bright pink sunburn. She recalls thinking: “I promise you, if I was dying over here, you would know about it. I would make noise.”

Large digital clocks show the time of day, down to the second, in red numbers. When the clock reaches the time on your sticker, you can go.

Then it’s back downstairs to the parking garage.

“The toughest part of the whole process is finding your car again,” says Clint Chiavarini, 49, a Metro data analyst vaccinated April 22. “The stairway that you come down is not the same as the one you go up.”

9. The After-Party

What do people do after a vaccination? They go to Denny’s.

The chain diner, two blocks down from the Oregon Convention Center, is playing “Hotel California” on a recent Thursday morning.

“This is my first time at Denny’s,” says Mindy Pham, 19, who has been working two jobs while she attends the pre-nursing program at Portland State. It was her first dose. She ordered a Lumberjack Slam—cinnamon pancakes, eggs, hash browns and toast.

“We were just like, ‘What are we craving?’ and we thought breakfast, because it’s so early in the morning right now.”

Denny’s is about a third of the way full. One employee half-whispers to WW, “We’re doing pretty well, as you can see.”

Several Lloyd District businesses have reported a spike in foot traffic since the clinic opened. The Burgerville drive-thru a block up Northeast Grand Avenue is consistently packed with 10 to 15 cars. Workers jog to waiting vehicles, paper bags of burgers in hand, searching for who ordered what.

Others celebrate vaccination the Portland way: They buy weed.

“There’s been a lot of spillover from across the street and coming over here,” says Fields Puckett, who works at Oregon’s Finest Cannabis, a dispensary right across the street.

“A lot of people have been proud and happy, or showed me their stickers,” adds Puckett. “Or people were like, ‘I wouldn’t be up this early normally.’”

In the five days a week the Oregon Convention Center is open, more than 40,000 people make this journey.

For Markesino, who tracks every detail down to the number of adhesive bandages used (as of last week, 401,891), the work is something he can tell future generations about.

“This is historic,” Markesino says. “In 20 years, people will say, ‘What was your role in the pandemic?’ I can honestly say, ‘We vaccinated 360,000 people.’”