Off-year elections are unglamorous affairs. No candidates for governor or senator will appear on your ballot when it arrives in the mailbox this week. Voter turnout is always low.

Yet this year, the key questions on those ballots are fiercely relevant to the concerns of Portlanders.

Three seats on the Portland Public Schools Board are up for grabs, at a moment when parents and teachers are fiercely debating how to send kids back into classrooms. And the Oregon Historical Society—a museum whose windows have been repeatedly shattered in anti-police riots—is asking voters to renew its property tax levy.

These contests don’t feature the kind of politics you see on cable news. But it’s here in the trenches where you’ll meet some of your fellow citizens most dedicated to public service. (In fact, a former city commissioner, Dan Saltzman, is running unopposed for a volunteer position on the board of Portland Community College.)

As always, WW invited the candidates in major contested races to meet with our newsroom and make the case why they should receive our endorsement—and your vote. (Look for our endorsement in a contested PCC race later this week on wweek.com.) When possible, we interviewed candidates together, in the same Zoom room. We asked them serious questions about the future of our institutions, along with a more lighthearted query (inspired by pandemic cabin fever) about their favorite class field trip.

We were reminded how many people are still seeking to make Portland a better, fairer place—even when no one is looking.

Portland Public Schools Board, Zone 4

Herman Greene

When Rita Moore, a parent activist, chose not to seek a second term on the School Board, her departure set off an unusually sharp-elbowed bit of jockeying for her seat. A taste of that friction: Four people filed to run for the office, then suspended their campaigns. Three more are on the ballot and actively campaigning; a fourth has mounted a write-in bid.

Thankfully, that tumult has produced an able front-runner: Herman Greene, the senior pastor of the North Portland church Abundant Life PDX. A Black leader who runs a summer mentorship program in the low-income housing tracts of New Columbia, Greene, 47, saw his own children through Roosevelt High School and is closely acquainted with the hopelessness plaguing the city’s poorest neighborhoods. (His wife and co-pastor, Nike Greene, runs the city’s Office of Violence Prevention which is trying to stem Portland’s rise in shootings.)

Wickedly funny, Greene ably handled a question on his independence from the teachers’ union, a key endorser. (He has most of the major endorsements in this contest, including Moore’s.) His detailed understanding of the district’s shortfalls in serving students of color will be instrumental as the School Board tries to fix a deeply inequitable system.

Greene faces an impressive write-in candidate, Jaime Cale, a Rosa Parks Elementary employee (she’d have to quit her job if elected) and an organizer of the racial justice group Mxm Bloc. Cale, 43, recently organized a rally against reopening schools during COVID-19. She at times offered inconsistent answers on whether schools should be open right now. She provided a thoughtful analysis of how the district is still failing children of color, but she did not compel WW to recommend a write-in candidate when a solid one is on the ballot in Greene.

Also running is Margo Logan, a fervent Trump supporter who has publicly espoused theories that match those of QAnon, and developed a conspiracy theory before our eyes—claiming the glitches in her internet connection were our attempt to shut her out of a Zoom meeting.

Another candidate, Brooklyn Sherman, is a Portland State University business student running on a platform that includes improving school playgrounds. That’s a cause we hope he’ll continue to champion. Greene gets our nod.

Greene’s favorite field trip: His most memorable was a middle school trip to a cave, where he wandered off with a friend, resulting in near disaster. It was his last time inside a cave.

Portland Public Schools Board, Zone 5

Gary Hollands

Hollands, 44, brings an unusual qualification to his bid for School Board: He owns a dump truck and teaches other people how to drive them.

That might sound odd. But Hollands’ work is important: He founded Interstate Trucking Academy, and trains students of color in long-haul trucking and garbage-truck driving. Those are family-wage jobs that have not always welcomed people of color.

He wants to increase trade education in schools so students feel encouraged to pursue “non-traditional” high-paying jobs like carpentry and construction if they don’t want to pursue a four-year college degree. He says the chasm between trade offerings at schools east and west of the Willamette River is too wide.

Hollands has a close view of the district’s practices: He’s a track coach at Benson High School. (He’s also married to an employee of the district, a potential conflict that makes us a little uncomfortable.) We like his emphasis on closing the learning gap between white students and students of color—and he can point to the places where the disparities start, including third grade reading.

Hollands has secured all of the key endorsements in this contest. His opponent, Daniel Rodgers, has none.

Rodgers, 33, is a family physician who joined the race late. His plans for improving hybrid learning are vague as are his criticisms of the district. He’s a nice guy, but we were frustrated by his loose grasp of the details of how PPS functions.

Hollands is well versed in those details, thanks to low-profile work that includes previously serving on the board of the Multnomah Education Service District. (It provides pencils and oversees special education.) We recommend you vote for Hollands.

Hollands’ favorite field trip: A trip to the Columbia Slough. It was the first time he’d seen frogs in the wild.

Portland Public Schools Board, Zone 6

Julia Brim-Edwards

We aren’t always sure why Brim-Edwards, 59, a longtime Nike executive, wants the often thankless job of Portland Public Schools Board member. But there’s no denying the steadying hand she’s applied to the district.

Think back to where PPS was when Brim-Edwards was first elected four years ago. Then-Superintendent Carole Smith had abruptly resigned after the discovery of lead in the water coming out of faucets and drinking fountains at several school buildings (and WW’s revelation that the district had hidden lead contamination at dozens more). A search for a new superintendent foundered when the board discovered its new hire had exaggerated his qualifications. The board itself was a nest of backbiting and mutual contempt.

Brim-Edwards hasn’t just righted the ship—she’s plugged its hull and bailed the water out of steerage.

Her most important task was steering the selection of a superintendent. She succeeded, leading what by PPS standards was a swift and collaborative process that settled on Superintendent Guadalupe Guerrero, who has so far proved capable. Brim-Edwards oversaw the opening of two new middle schools, championed the rebuilding or renovation of half a dozen campuses and, perhaps most importantly, opened the books on the health hazards in the district’s aging buildings.

Not everything Brim-Edwards touches turns to gold. The pandemic has cast an unforgiving light on the inequities of the district, where affluent, white children are more likely to return to classroom instruction.

COVID-19 has upended every school district in the nation and makes it harder to grade Brim-Edwards’ performance. But compared with when she arrived, PPS looks far more stable and vigorous.

The name “Nike” doesn’t warm the heart of every Portlander, and Brim-Edwards’ role leading government affairs at Oregon’s sportswear giant rankles some observers.

That frustration was aired several times in our endorsement interview by Brim-Edwards’ challengers: Max Margolis, a reading tutor with a background in crime and drug prevention programs, and Libby Glynn, co-president of the Bridger School Parent Teacher Association with a background as a researcher and supervisor for a catering company. Both offered good ideas—Glynn in particular made sharp observations about how PPS treats students with disabilities—but neither offered a compelling rationale for unseating the incumbent.

Brim-Edwards has earned the opportunity to show what she can do once the district is free of the virus. Keep her on the board.

Brim-Edwards’ favorite field trip: A tie between Franz Bakery and the Bonneville Locks to watch the salmon migration.

Measure 26-221

Oregon Historical Society levy

Yes

History museums belong on the ballot. They are political institutions.

Their curators decide which artifacts we preserve, whose heroes we venerate, and what shameful events we confront. Those choices have rarely been more contentious than over the past decade, when the renaming of buildings and the toppling of statues threw open the question of whose past should be part of our present.

As it happens, these were also the first years when the Oregon Historical Society was receiving tax dollars. A property tax levy first passed by Multnomah County voters in 2011, and renewed in 2016, funds the museum and its archives to the tune of nearly $4 million a year.

Multnomah County now asks voters to renew it for another four years. The levy costs homeowners 5 cents for every $1,000 of assessed property value. If your house is worth $200,000—roughly the median home value in the county—you’ll pay $10 a year, less than the price for one month of Netflix.

Five years ago, when this levy was last on the ballot, we expressed some skepticism about a private nonprofit snagging taxpayer money. But OHS has proven its public worth—not least by providing free admission to all Multnomah County residents.

Those visitors quickly grasp where OHS has landed on the question of how to tell Oregon’s story. It is perhaps the most decisively anti-racist museum in America. Its latest exhibit, Experience Oregon, begins and ends its journey with the fate of Native American tribes. It displays a Ku Klux Klan hood to confront patrons with Oregon’s legacy of bigotry. The society’s quarterly magazine dedicated a recent issue to a scholarly consideration of white supremacy.

As WW noted in a celebration of the museum earlier this year: “It is striking, the degree to which OHS is emphasizing the ugliest parts of Oregon’s heritage and presenting them as repulsive.”

Some people want to look away. OHS executive director Kerry Tymchuk likes to tell a story about a recent visitor who felt uncomfortable about what he saw. “You make me feel guilty for being a white man,” he said.

Tymchuk replied: “You’re not responsible for what happened 150 years ago. But you’re responsible for knowing what happened.”

He’s right: Grappling with the past is a civic duty. Lately, that work is under attack from the political fringes, which seek either to enshrine society’s errors or erase them.

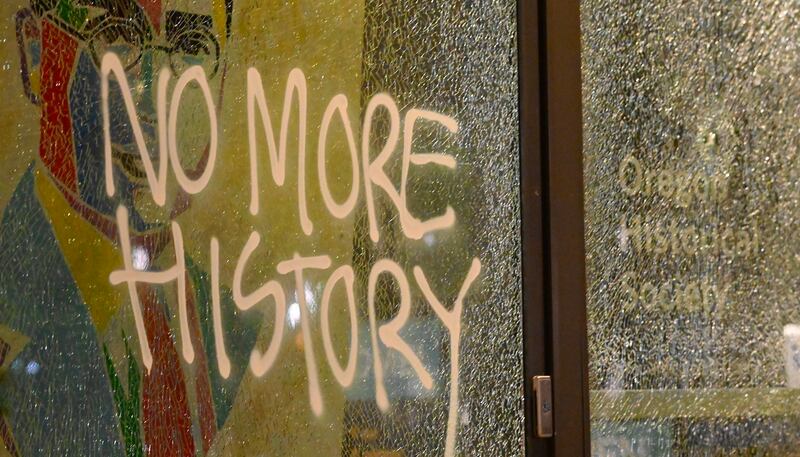

You’ve probably noticed the historical society in recent headlines. This winter, the museum installed shatterproof glass after rioters broke windows, tossed a flare in the lobby and dragged a quilt made by Black women through the rain-soaked streets. This month, black bloc marchers struck again—and the glass cracked in a spider web pattern, but didn’t shatter. One of the vandals spray-painted a nihilist message: “NO MORE HISTORY.”

Our reply: More history. Fund this museum.