Racism, financial hardship and abuse are just a few of the traumatic childhood experiences Black Oregonians face at disproportionately higher rates than other races, according to recent findings by state health officials.

When children undergo these forms of trauma before the age of 18, they are known to the health professions as adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs. They increase the likelihood of physical and behavioral health ailments going into adulthood, says Portland pediatrician Dr. Deidre Burton.

ACEs include physical and emotional abuse, witnessing domestic violence or substance abuse, and having an incarcerated parent—among many others.

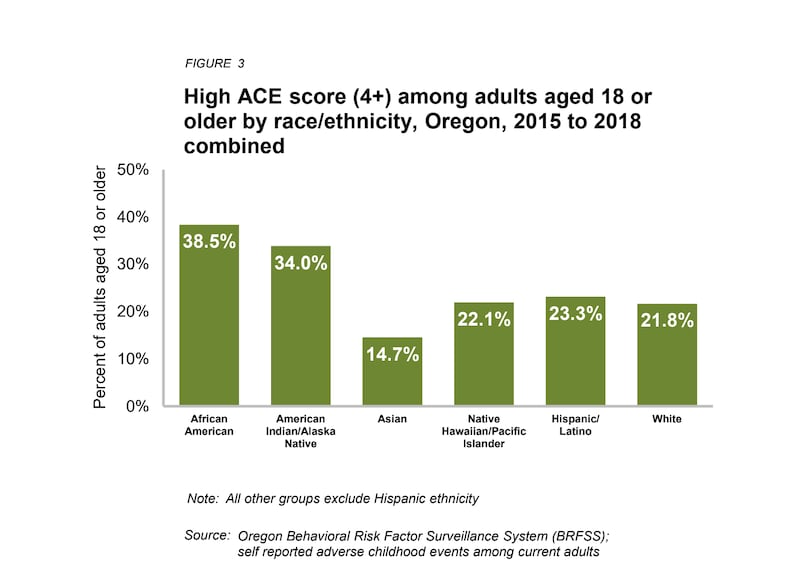

From 2015 to 2018, Black people reported experiencing more forms of trauma as children than any other racial demographic, with 38.5% reporting four or more ACEs, according to the Oregon Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a survey conducted by the Oregon Health Authority. Just 21.8% of white people reported having more than four ACEs.

Like most other racial disparities, it comes as little surprise.

“Of course our scores are going to be higher because of financial hardship and the environment lived in and the experience of racism itself,” Burton says.

The COVID-19 pandemic can be added to the list of traumatic experiences, says Burton, who has been in private practice in Portland since 1994 and is affiliated with hospitals that include Legacy Emanuel.

The disparity is devastating, she says. Along with higher case rates and deaths, the pandemic’s effects include isolation.

“More Black children have experienced the loss of a loved one disproportionately, and they have been left home because their parents are on the front line. Because of the economic disparity, their parents have not had the luxury to stay at home and work virtually,” Burton says. “Black children have been left to fend for themselves.”

A high ACE score often portends other problems, Burton says: diabetes, heart disease, obesity, and substance abuse—”which then creates an environment for my children that perpetuates that cycle.”

Doctors need to start recognizing, she says, that poor health begins before its symptoms appear.

“I think people broadly need to understand what ACEs are and what the impact is,” Burton says. “As health care professionals, we need to screen for ACEs. We need to talk about resilience and teach our kids coping skills. On a societal level, we need to start to address the disparities.”

This reporting has been funded in part by a grant from the Jackson Foundation. See more Black and White in Oregon stories here.