The Nabisco strike that began when union bakers walked out of the Oreo and Ritz factory on Northeast Columbia Boulevard on Aug. 10 continues to fester—but Nabisco’s parent company, Mondelez International, has taken aggressive steps to combat the strikers’ tactics and keep its operations going.

On Aug. 31, the company sent a cease-and-desist letter to the union—warning strikers the company would pursue legal action if they didn’t stop interfering with plant operations.

And then, on Sept. 2, Portland police kicked strikers off property beside the railroad tracks where strikers positioned themselves to block trains carrying supplies to the bakery by holding up picket signs, which union railroad workers honored.

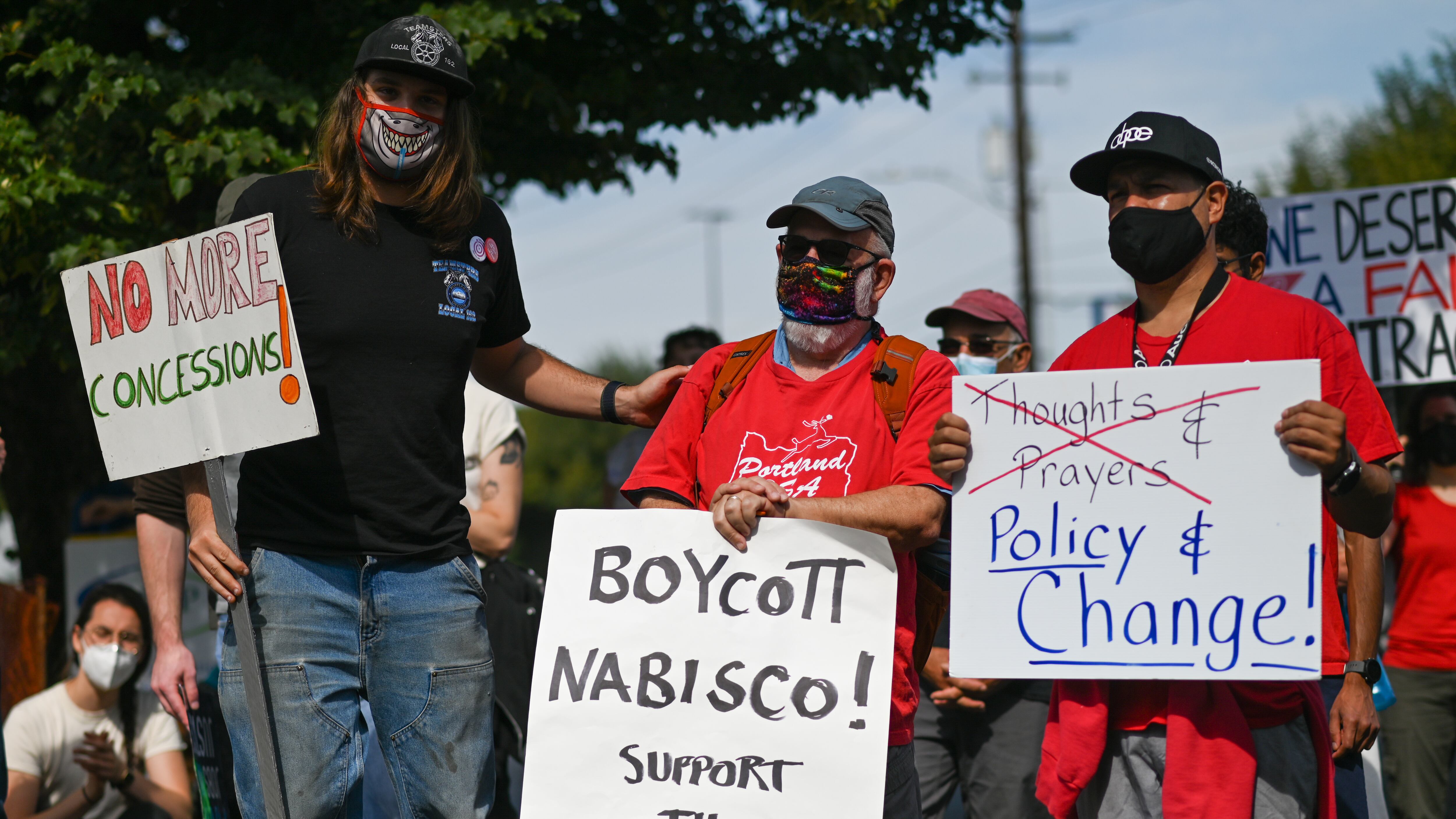

Nearly 200 members from the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union Local 364 went on strike to protest Mondelez’s proposed new contract. The union says the contract would strip away overtime pay and provide less robust health coverage. Every day since, strikers have waved homemade signs, wielded bullhorns, and cheered at cars whizzing along the major road where the bakery stands.

The strike comes at a time when Americans, stuck at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, are loading up on snacks like Oreos and Ritz crackers—both Nabisco products. It also comes at a time when skilled laborers, such as bakers, are in high demand.

The Portland strikers touched off strikes at other Mondelez bakeries and distribution centers across the country, as WW has reported. And since late August, a rotating group of strikers has occupied space near the Union Pacific railroad tracks to stop incoming trains carrying cooking oil, sugar and flour. Unionized railroad workers have honored the bakers’ picket line.

But Mondelez, which is currently operating the plant with nonunion replacement workers, recently took steps to preserve its supply lines.

On Thursday afternoon, Portland police officers told strikers they had to vacate their post alongside the railroad tracks within two hours.

Mondelez is also threatening legal action against the union. The company’s attorneys sent a cease and desist letter to the baker’s union Aug. 31 warning strikers to halt hostile actions or they’d sue.

Mondelez’s attorneys laid out what they believed were unlawful actions.

The letter alleged that strikers had damaged Mondelez property, including using a knife to puncture the tire of a security car and pouring beer into a security vehicle. The company also alleges the union unlawfully blocked entrances and exits to the facility, including an external parking lot that Mondelez leased for strikebreakers several miles from the bakery.

WW reported last week that a group of leftist protesters took decisive actions—three of which were detailed by Mondelez in its letter—to impede strikebreakers brought in through Huffmaster, a strike staffing company.

The attorneys also called local union business agent Cameron Taylor on Thursday afternoon, stating their intent to seek a temporary restraining order against the union.

The union immediately shot back on Friday. It hired attorney Margaret Olney, who wrote a letter to Mondelez in response to the cease-and-desist letter and proposed “rules of engagement” for the strike.

Olney argued that the company’s allegations of misconduct applied to actions taken by outside supporters of the strike, not union members themselves. Such actions would have had to be approved by the union, she said, for it to be held responsible.

“To obtain any injunctive relief against the union or its officers/members, there must be ‘clear proof’ that the illegal acts were authorized and ratified by the union,” Olney wrote. “We do not believe the employer will be able to come close to meeting that burden, particularly given the fact that the involvement of nonunion activists over which the union has no control.”

In response to Mondelez’s allegation that strikers yelled racial slurs at a strikebreaker who crossed the picket line, Olney said the union was not aware of such an action taking place but had told its members such comments would not be tolerated.

As for strikebreakers occupying Mondelez’s land beside the railroad tracks, Olney said the union immediately rectified the matter once police officers showed up: “This should be a non-issue and is certainly not the basis for a [temporary restraining order]. As you know, the statute requires evidence of a continuing violation, as well as a failure of law enforcement to take action.”

Three hours after WW published a story about Mondelez seeking a temporary restraining order against the union Monday afternoon, Olney says, she received a text from Mondelez’s attorney saying the company was no longer pursuing the order—for now.