Portland is having a midlife crisis.

For much of the past decade, this city enjoyed an image with a skyward trajectory: attractive, clever, basking in the spotlight as national media spoke of our promising future.

Then, suddenly, we melted down on the national stage. And after a year of flaming dumpsters, sidewalk shantytowns and unsolved murders, Portland became a punch line.

Be honest: How often in 2021 have you responded to an aunt from back home, a college buddy, or a business acquaintance who asks about Portland with “It’s not really that bad”? As a new civic slogan, it leaves something to be desired.

Amid this disorientation, you know what might help? A book of maps.

Two Portland State University professors, Hunter Shobe and David Banis, have written a sequel to their regional bestseller Portlandness: A Cultural Atlas, which compiled defining characteristics of the Rose City using cartography. Their new book also uses maps, comparing PDX to Seattle and San Francisco, the crunchy, evergreen North-Left Coast of America.

Or, to use the title the authors chose, Upper Left Cities (Sasquatch Books, 224 pages, $30).

It’s a somewhat eccentric compilation of everything from which city has the most alleys (Seattle), the most ramen shops (San Francisco) and the most Russian speakers (Portland). Some maps—like the one at left, showing shops selling analog goods in 1987—are especially playful. The measurements range from the whimsical (there’s a chapter on lost amusement parks) to the technical (where the cheapest gasoline in each city is found) to the current: Two pages consider where in each city the most people contracted COVID-19.

The comparisons are often enlightening. It’s one thing to hear that homelessness is a scourge of the whole West Coast and quite another to see maps of where Seattle and San Francisco’s largest camps have grown. Indeed, one of the themes of the book is that Portland is really part of a single Pacific Northwest city that votes, eats and plays in much the same way.

“All the Northern Calfornians moving up to the Northwest—I think they feel comfortable here,” Banis says. “The voting patterns might be identical. [Portland] feels like a small version of San Francisco in a lot of ways.”

In the following pages, we’ve mostly chosen maps that show how Portland differs from its neighbors. The PSU geographers found big differences in housing costs, weed shops, and what kind of air freight arrives at the cities’ airports.

The portrait that emerges suggests that Portland is, more than anything, young.

Not just by median age—although we are the most youthful city of the three, in part because millennials in Seattle and San Francisco are even more averse to breeding. Portland is different from its siblings because it’s a city where (some) newcomers can still afford to live, an economy that isn’t as strapped to large corporate engines, and a population that is less inclined to follow the rules.

In other words, we’re a city in crisis partly because we can still argue about who we should be.

For decades, Portlanders have resented being compared to Seattle and San Francisco. But while the measurement isn’t always flattering, it is a little freeing. Of all the Upper Left Cities, Portland is the least successful, the least steady. That means we’re the place with the most possibility to change.

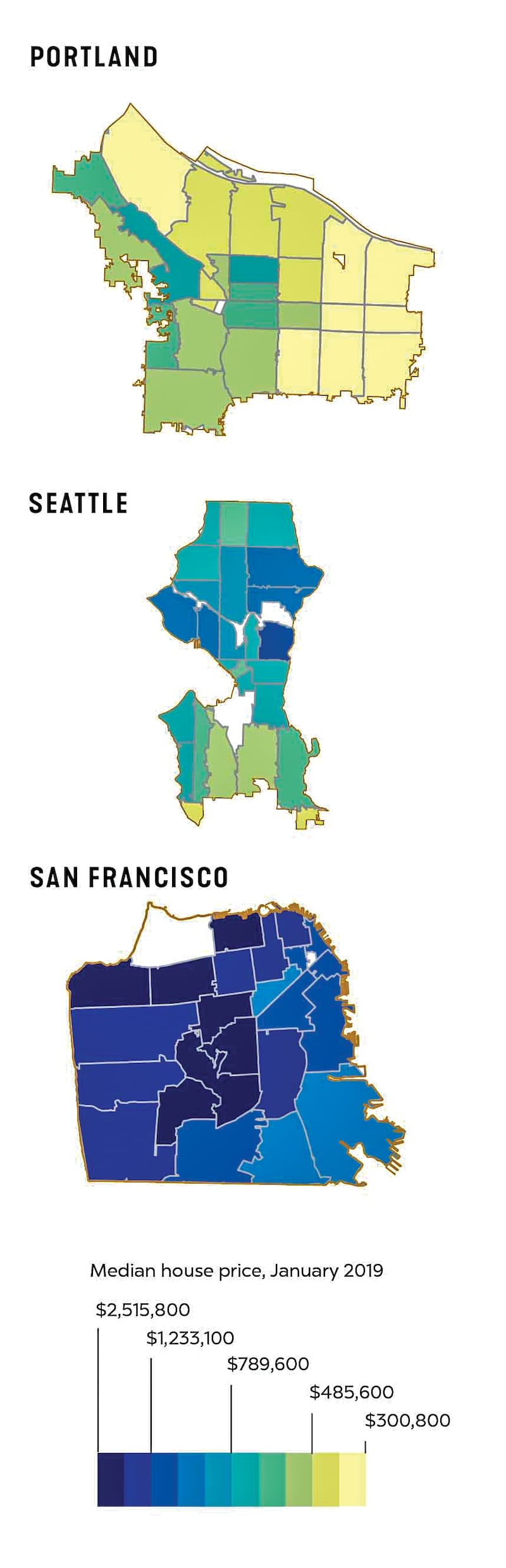

Houses are much cheaper in Portland than in Seattle or San Francisco.

Portland’s housing crunch looks both better and worse after glimpsing skyrocketing real estate prices in its sibling cities. Better, because a standard home selling for a quarter-million dollars in any inner Southeast Portland neighborhood is a bargain compared to the median-priced home in several San Francisco neighborhoods selling for upward of $2 million. Worse, because people living in San Francisco can also recognize a bargain when they see it.

“It doesn’t take looking at this for long,” Shobe and Banis write, “to understand why so many people from San Francisco have decided, after years of making San Francisco money but paying San Francisco prices, to relocate to Portland or Seattle.”

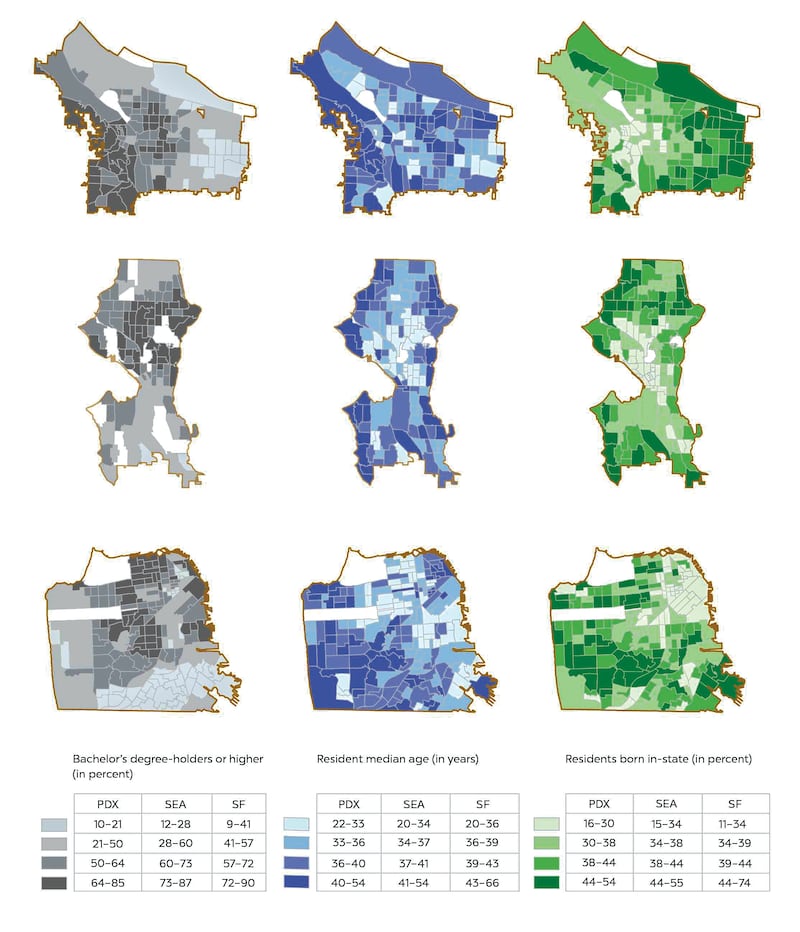

Another tension underlies fear of the marauding California homebuyer: Both Seattleites and Bay Area denizens are, on average, better educated than Portlanders. Sixty percent of Seattle residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, while in Portland that figure is 49%. “In these places where you have the most affluence,” Shobe tells WW, “you also have the highest rate of education.”

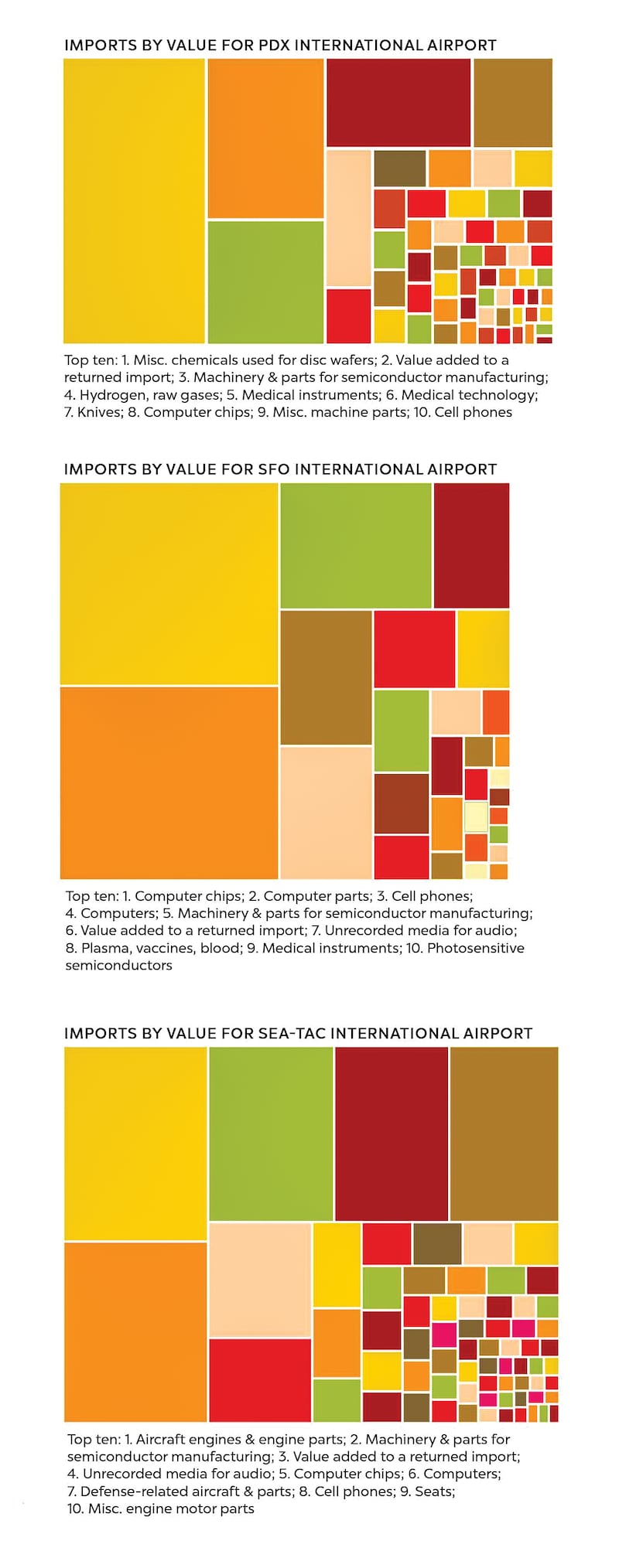

Portland sees far less goods landing at the airport.

In 2018, $1.98 billion in trade passed through Portland International Airport. That sounds like a lot, until you measure it against the value of goods imported and exported through San Francisco ($66.4 billion) and Seattle-Tacoma international airports.

How to explain this lag? (After all, we have the best airport in the country—it even has a Mo’s Chowder!) Take a closer look at the kinds of goods being imported. In San Francisco, the top import is computer chips, destined for iPhones. In Seattle, it’s airplane engines and engine parts—linked to Boeing.

University of Oregon economics professor Tim Duy isn’t surprised by the finding. “Your imports are going to reflect whatever your local economy is doing,” Duy says. “They are bigger economies.”

If it’s any comfort, Portland’s actual port does twice the business of San Francisco’s, thanks to its status as the Pacific Coast’s top exporter of automobiles.

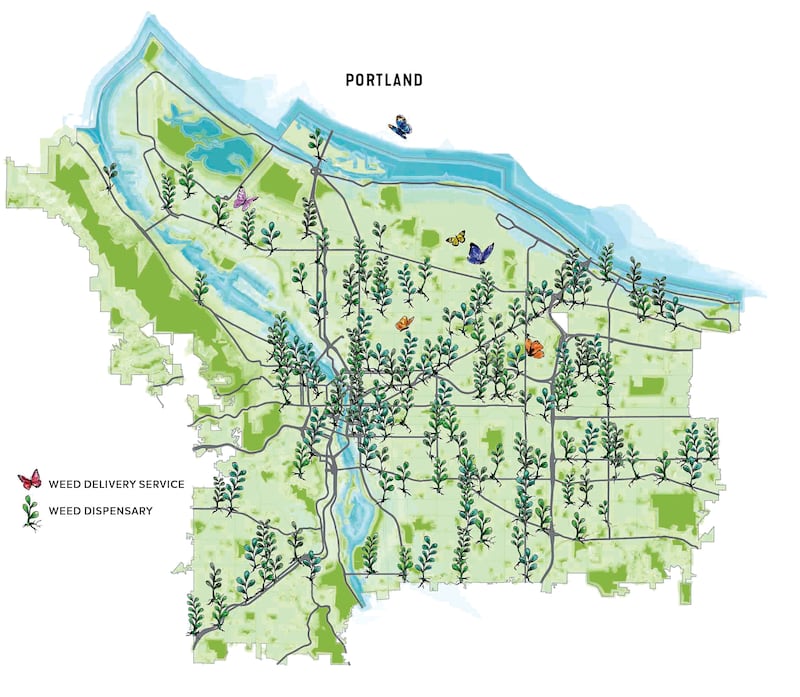

We have far more weed shops.

Starting to feel that bad old little brother complex? Relax. We have far more cannabis dispensaries than San Francisco or Seattle, and they’re distributed far more broadly across the city. “When we saw the maps, we almost couldn’t believe it ourselves,” Shobe says. “It seemed like there was double, or something like that.”

Shobe credits the blooming of weed outlets to Oregon’s libertarian streak—he sees it as a similar phenomenon to the liberal siting of strip clubs across Portland neighborhoods.

Beau Whitney, a Portland cannabis economist, says Oregon was indeed more loose in handing out pot shop licenses than Washington and California, which strictly regulated the recreational cannabis market. “In Oregon, there were no caps in retail licenses,” Whitney says, “as long as they weren’t near schools or day cares and the like.”

The drawback: More shops means lower sales figures at each dispensary, and that’s squeezing a lot of entrepreneurs out of business despite hearty demand for bud.

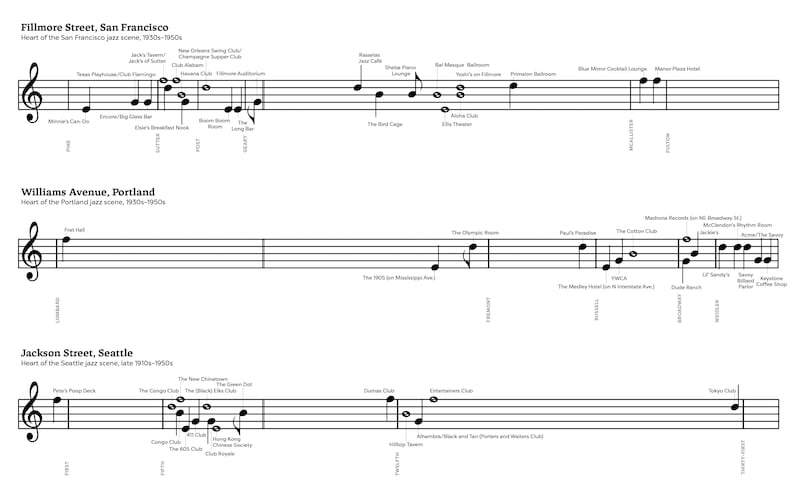

We share a sad history of shuttered jazz clubs.

One small but tangible way to measure the racism perpetuated by this city? Look at the lost jazz clubs that once flourished on North Williams Avenue. The closure of such clubs is a kind of shorthand for the destruction of the neighborhood that contained them: Albina, the center of Black Portland, was torn apart when transportation officials carved Interstate 5 down its center.

It is a shameful chapter in Portland’s history. Yet Seattle and San Francisco have similar stories—and streets that are shorthand for a vanished jazz era. (It’s Jackson Street in Seattle, Filmore Street in San Francisco.)

“In each city, you have this area that becomes really vibrant in one of the cores of African American life,” Shobe says. “And then we see this national block-busting situation, the renewal where you call something blighted that’s actually very alive.”

The tribute Upper Left Cities pays to these clubs is one of the most creative maps in the book. Banis maps the three streets where jazz reigned by drawing them as sheet music, with each vanished club’s location marked by a musical note. Banis says it’s possible to play the composition. “It sounded alright,” he says.

Portland’s George Floyd protests were longer and more intense.

The effects of 100 consecutive nights of street confrontations between police and protesters on Portland’s civic psyche were immense—and, at times, overstated for political effect (see “Bad Reputation”). But it’s clarifying to realize how much more stamina and energy the uprising had here, compared to cities where voters also went for Biden at a 10-to-1 clip.

Long after San Francisco demonstrations petered out and Seattle’s were largely cordoned within the Capitol Hill area, Portland marchers besieged police precincts and braved tear gas across the city. Progressive political consultant Gregory McKelvey says Portland protests gained momentum from trauma. “Portlanders who have not experienced the flash bangs, tear gas, pepper spray, and beating really do not understand the toll it takes on someone,” McKelvey told WW earlier this year. “Imagine watching someone beat your best friend, or gas your children, or arrest your grandmother. That would make anyone angry.”

Related: The chaotic image of Portland peddled on FOX News has prevailed—more than you might think.

Some of what happened can be traced to then-President Donald Trump seeking a show of force in Portland to bolster his reelection campaign. But Shobe noticed another factor: People with the motivation to confront cops can still afford to live in Portland, but were largely priced out of the Bay Area. “Somebody who has activist ideals,” he says, “I think that people who fit that description might have an easier time paying their bills in Portland.”

GO: Hunter Shobe and David Banis will discuss Upper Left Cities in a virtual event presented by Powell’s Books at 5 pm Thursday, Sept. 30. Free. Tickets are available here.