On Nov. 13, 2019, Willy Hollings dashed off a quick text message to a friend.

“The 7 mag did some work on the way home today,” wrote Hollings, referring to his 7mm Remington Magnum rifle. He attached a cellphone picture of three cougar cubs—dead.

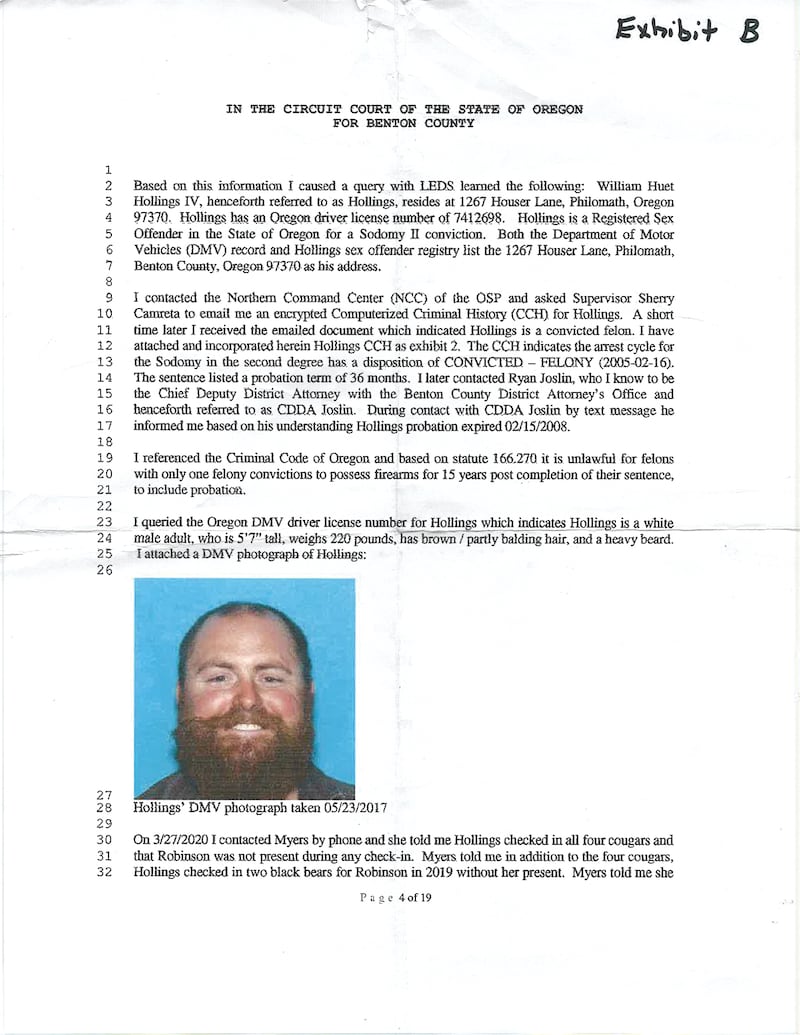

Police investigators believe Hollings, a stocky, full-bearded 36-year-old, shot the cubs in Oregon’s Central Coast Range, driving back from his job with a Philomath logging company.

It wasn’t his first time killing cougars, which Oregonians can legally hunt under specific circumstances. It wasn’t even his first that month.

Oregon is home to some of North America’s most magnificent wildlife, including wolves, black bears, and Roosevelt elk, named after the 26th president. In his 1893 book, The Wilderness Hunter, Theodore Roosevelt described elk as “lordly, antlered beasts” that are “perhaps the most majestic-looking of all the animal creation.”

More than a century later, conservationists and outdoors enthusiasts agree that the large mammals that roam Oregon’s mountains and forests are the state’s treasure—one of our last connections to wilderness.

For Hollings, they were dinner.

But the meals weren’t always tasty. “This cougar is bland as fuck,” he texted a hunting buddy and co-defendant in January 2019. “Should have had it with taters.”

Last year, Willy Hollings—born William Huet Hollings IV—was snared in what may be Oregon’s largest poaching bust since state lawmakers passed a package of laws in 2019 that changed the crime of poaching from a misdemeanor to a felony.

To Portlanders, this might seem an obscure problem.

Hollings and friends weren’t doing what a layperson might more commonly associate with poaching, like selling bear gallbladders on the black market, importing exotic animal parts from overseas, or leaving kills to rot in the woods.

But they weren’t playing by the rules.

For at least a year, prosecutors allege, Hollings and his friends Nicholas Lisenby and Eric Hamilton went on a poaching spree through the forests of at least four Oregon counties, killing more than 30 big game animals, including elk, cougars, mule deer, bears and bobcats.

Investigators say the trio exceeded their tag limits, hunted animals that were too young, killed others when they were out of season and, in some instances, hunted in the dark using spotlights.

The scope of their alleged activities spanned hundreds of miles. So far, prosecutors in Lincoln, Benton, Linn and Polk counties have filed more than 40 counts of poaching-related charges against the crew collectively. So far, the defendants have pleaded guilty to or been convicted on 13 counts. Two more cases, one each for Lisenby and Hamilton, remain open.

Sgt. Jim Andrews of the Oregon State Police Fish & Wildlife Division, who led the state’s investigation, says Hamilton and Lisenby grew up hunting and, to some extent, viewed their poaching as a means to feed their families.

“But then it morphed into something more with Hollings to the point where it almost seemed like he was feeding an addiction,” Andrews says.

The seeds of Hollings’ obsession sprouted in text messages with his buddies. Those digital missives would become the central evidence in the state’s cases against him and the two others.

From at least December 2018 to March 2019, search warrant affidavits show, Hollings and his pals exchanged hunting advice via text messages.

They discussed which guns and scopes worked best for long-range shooting, sought contact information for an “under the radar” taxidermist, and made appointments for elk hunts. They shared so many photos of kills that Hollings’ girlfriend later told police she lost track of which man had bagged what.

On Jan. 19, 2019, Hollings and Lisenby exchanged approximately 100 messages. Near the end of the string, Lisenby asked Hollings if he planned to go hunting in Alsea, Ore.

Hollings replied: “Yep. Probably next week. Then black rock”—a mountainous area near Falls City. Seconds later, Hollings added one final thought:

“Things will die.”

To understand why Hollings’ actions so trouble Oregon law enforcement, you have to go back 109 years.

The snow was nearly 4 feet deep in the Wallowa Valley on March 14, 1912. It was Thursday—a school day—but class was not in session. Businesses had shut down for the day. An estimated 10,000 spectators gathered at train stations across the region, hoping to catch a glimpse of history passing by: the arrival of 15 elk being shipped by train from Jackson Hole, Wyo., to restore Oregon’s elk population.

The elks’ arrival signaled the revival of Oregon’s ecosystem. By 1900, “America’s elk teetered on the brink of extinction” because of lax hunting regulations and the commercial sale of elk parts, namely teeth and tongues, writes author Mark Highberger in The Elk Killers.

(Elk tongues were considered a delicacy. Roosevelt, in his 1885 book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, called them the “most delicious eating, being juicy, tender, and well flavored.”)

News of the decimated population sparked public outrage. It prompted an outright ban on elk hunting in Oregon, which lasted for decades until the population recovered.

The Jackson Hole elks’ arrival in 1912 may seem eons ago. But poaching is an ongoing problem today. It’s also a crime that’s uniquely difficult to detect, often occurring in very rural areas with few witnesses.

“The victims obviously cannot speak up for themselves,” says Sristi Kamal of Defenders of Wildlife. “And then evidence—including the victim—is easy to hide or dispose [of].”

Without the ability to enforce poaching regulations, the state’s wildlife populations risk a repeat of the early 20th century.

“We’ve seen what could happen,” says Curt Melcher, director of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, “and that happened back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when essentially elk were all but extirpated from Oregon. And the same is true and would be true with other species.”

Anti-poaching officials will tell you the state’s wildlife belongs to everyone who resides here, meaning poachers are stealing from even the least outdoorsy among us. And poaching affects the Portland metro area, too, particularly birds, including bald eagles and red-tailed hawks.

In 2019, Oregon State Police tallied 324 instances of illegal killing of big game animals. In 2020, as many Oregonians found themselves with idle hands amid a pandemic, that number increased to 417.

Those are the illegal animal killings that OSP can confirm. State researchers and police say the actual figures are likely much higher.

Investigators and lobbyists say compulsion to kill big game animals—with no financial incentive—is an increasingly common motive for poachers.

“In the past five years, we’re starting to see a lot more illegal take that is, to be blunt, more of a thrill-kill model where the animal is just shot and left—almost like people are doing live target shooting,” says Steve Hagan, vice president of the Oregon Hunters Association, a lobbying group. “For them, this criminal activity is their version of a drug.”

The Oregon State Police’s recipe for catching poachers often starts with hauling a taxidermied deer into the woods, then waiting for somebody to shoot at it.

During a tour of the agency’s Astoria office, OSP Fish & Wildlife Sgt. Joe Warwick unlocks an exterior door to reveal a windowless room. Inside: one massive taxidermied elk on the floor to the left of the door, and four taxidermied black tail deer hanging on the wall two by two, like a macabre display of Santa’s reindeer.

These mounted “decoys,” as OSP calls them, are illegally slain animals the agency recovered during poaching investigations. They’re taxidermied for the specific purpose of catching poachers. (Oregon law does not distinguish between shooting at a live animal versus a decoy.)

Warwick says the decoys are stuffed with foam, and the bigger ones—like the elk—weigh about 80 pounds. When it rains? Add another 30.

“It’s kind of a pain. You gotta carry this thing out into a clear-cut during the day,” Warwick says. “In fact, we had a trooper get a compound fracture last year carrying the elk decoy through a clear-cut. I guess that’s one of the dangers of the job.”

Poaching was classified as a class A misdemeanor in Oregon, which is punishable by up to 364 days in jail and a $6,250 fine. But in 2019, authorities busted a father-son duo from Longview, Wash., who led a poaching ring that killed dozens of big game animals and led to nearly 200 counts of poaching-related charges in Oregon and Washington courts.

“This was an organized killing spree,” testified Paul Donheffner, legislative committee chair for the Oregon Hunters Association, during the 2019 session. “They weren’t hunting. They were out to destroy our wildlife.”

That case was part of the reason the Legislature in 2019 passed a pair of anti-poaching bills.

House Bills 3035 and 3087, co-sponsored by Reps. Ken Helm (D-Washington County) and Brad Witt (D-Clatskanie), changed poaching from a misdemeanor to a felony if the poacher is found to have a “culpable mental state” or if the acts were committed “intentionally, knowingly or recklessly.” That means a maximum five-year prison sentence and a $125,000 fine.

In addition, HB 3087 allocated $4.4 million to fund an anti-poaching awareness campaign run by ODFW, the purchase of about 65 trail cameras, and the hiring of four OSP Fish & Wildlife troopers and a roving assistant attorney general to assist county prosecutors statewide in poaching cases, says ODFW’s Stop Poaching Campaign coordinator, Yvonne Shaw.

“Some very, very evil people—there’s no way other than that to explain it—they enjoy killing,” said Witt, a longtime hunter, in a recent interview with WW. “There is nothing more reprehensible, gut-wrenching, than people who kill for the pleasure of killing.”

One year after the legislation passed, state troopers interviewed a Philomath woman who described just the case they were looking for.

In March 2020, somebody submitted an anonymous complaint to OSP’s “Turn in Poachers,” or TIP, line. The tipster said Willy Hollings and his girlfriend Shannon Robinson had just broken up and that “he had never known Shannon to hunt.”

That matched a hunch that state troopers were already following.

The previous November, Hollings brought the skull of an adult female cougar into an ODFW check-in station, as state law requires. About a week after that, he brought in three more cougar skulls—all juveniles—that were killed in the same location as the adult cougar from the week before.

In Oregon, it is illegal to kill cougars with spots, or a female that is with them. The spots, which fade within about 18 months, indicate the animal is possibly still nursing.

So when Hollings brought in three juvenile cougar skulls but did not bring their pelts along with them about a week after bringing in the adult female’s skull and claimed two of the four were killed by his girlfriend, that set off alarm bells for department wildlife biologist Anne Mary Myers. Maybe these were cubs.

Investigators reached out to Robinson, who had left Hollings after 11 years and was willing to talk. During an interview on April 4, 2020, at the Philomath Police Department, Sgt. Andrews and two other officers questioned her about Hollings.

Robinson remembered him boiling a skull.

It belonged to a forked-horn buck. The do-it-yourself taxidermy technique melts flesh off of bone.

The memory of the submerged skull was one of several key details Robinson told investigators she had witnessed during the two years she and Hollings lived together under a red tin roof in their Philomath home, according to search warrant affidavits reviewed by WW.

Robinson described guns on a wooden rack. More in Hollings’ black work truck. At least 10 firearms total.

Freezers with meat of the mammals he’d killed and butchered. A deer in the bed of the black pickup. Two cougars. A spike elk. A black bear that Hollings wanted to get mounted because he killed it on the last day of the season and because “he was somewhat attacked by it after he initially saw it.”

She recalled an elk skull mounted on the wall in Hollings’ shop. Maybe it was the same one he had boiled, but it was hard to be certain. Especially with all the cellphone pictures of Hollings and his buddies posing with slain animals. Who had killed what became a blur.

Some of what Robinson described to police, like an allegation that Hollings killed animals using her tags, was clearly poaching. Other instances may have qualified as legal hunting—except Hollings was convicted of a felony sex crime in 2005 and therefore prohibited from possessing a firearm.

Shortly after interviewing Robinson, state police determined they had enough evidence to search Hollings’ home, vehicles and electronic devices, and to analyze data from his iPhone—even text messages Hollings had deleted.

“Girlfriends, ex-wives—they come into play many times,” ODFW’s Melcher says. “In situations like this, the state police in many years have developed cases because an ex-wife or ex-girlfriend will tip them off.”

On April 8, state troopers served the warrant at Hollings’ home. They seized an iPhone and iPad, a Ruger .338 Magnum rifle, a spotlight, a gun silencer, 400 rounds of ammo, and the skull and antlers of a five-point bull elk.

The spotlight was particularly important.

Investigators allege Hollings used it to kill animals in the dark, either before or after work on the logging crew. Hunting is prohibited within 30 minutes of sunrise and sunset, in part because many big game animals are nocturnal. But spotlights are considered especially unsporting.

“It’s really taking advantage of their senses more than anything,” OSP’s Andrews says. “Hunting is supposed to be somewhat fair. Lots of deer and elk, you shine ‘em with a spotlight in the middle of the night and they just stand there and stare at you, and that’s not normal behavior for them.”

With a judge’s approval, OSP Detective Clint Galusha used Cellebrite, the Israeli surveillance company, to extract deleted text messages from Hollings’ iCloud account.

And in the cloud were hundreds of text messages between Hollings, Hamilton and Lisenby in which they discussed their activities.

That February, for example, Lisenby texted Hollings his recipe for an elk he had killed.

“Stuffed rear hind quarter for dinner…Yummy yummy,” Lisenby wrote. “Just took it out of the oven…Took some main muscle sections cleaned them up slit them down the center. Filled them with cream cheese and jalapenos.”

“Oh my,” Hollings responded, seemingly impressed.

Many of the text messages would later serve as the building blocks for prosecutors’ cases against them.

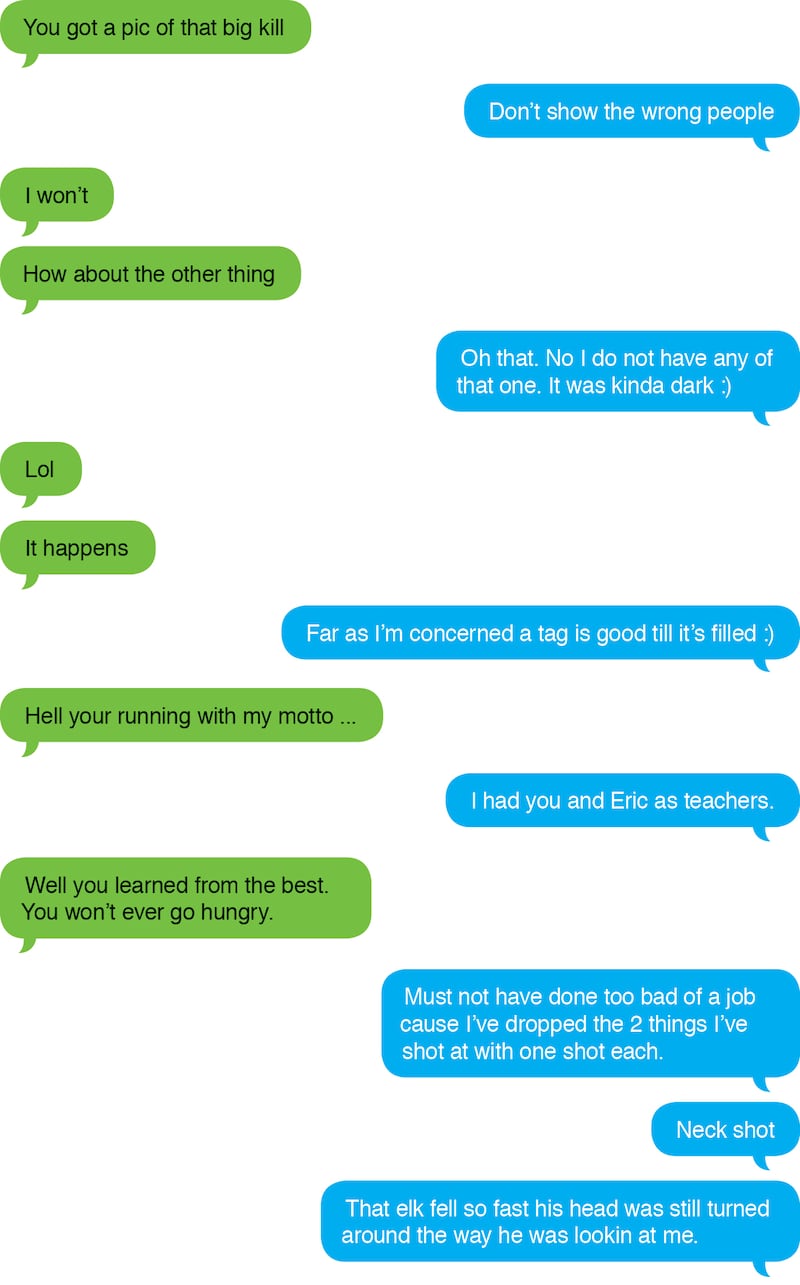

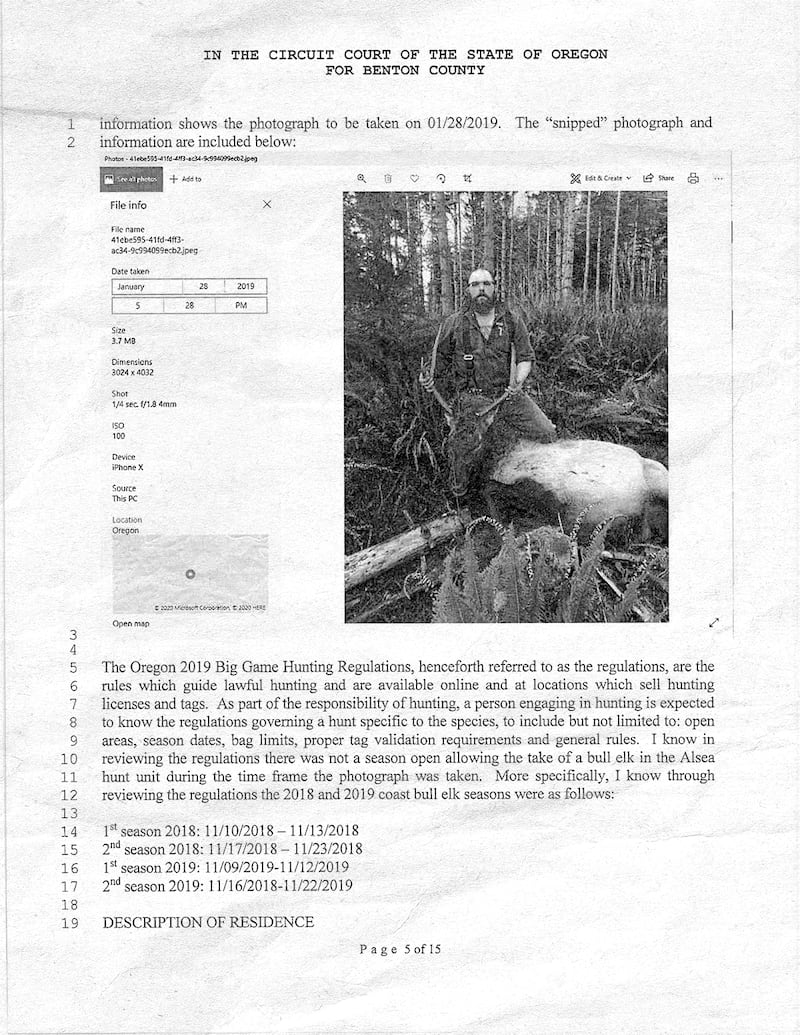

One texted photo was especially damning.

On Jan. 28, 2019, Hollings texted Hamilton and asked him to send a picture, presumably from earlier that day. Hamilton responded with photos of Hollings holding up a four-point elk. It was not elk hunting season, meaning it was illegal to kill the animal at that time.

Hamilton added a message:

“Fuck yea bro. wouldn’t miss it for the world. You’re a stone-cold killer.”

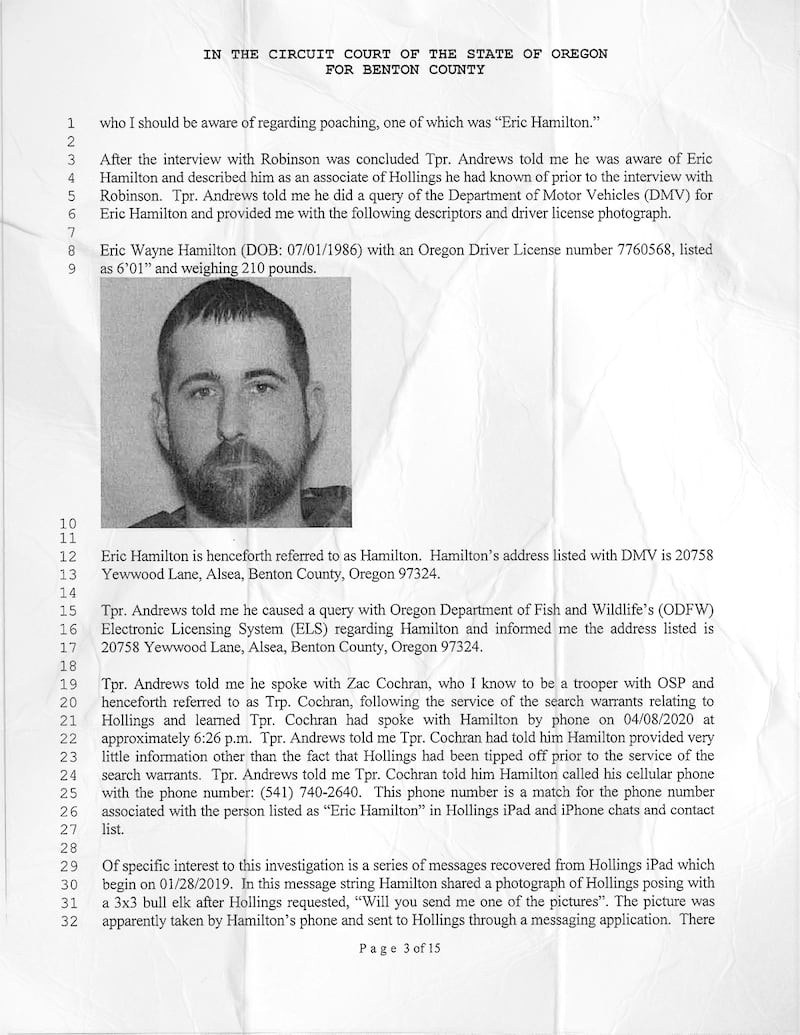

Prosecutors had more evidence beyond text messages. On April 25, 2020, police served warrants on both Lisenby and Hamilton.

At Lisenby’s house, they found 11 packs of elk meat, five packs of deer meat, three containers marked “broth” in his freezer, and a cougar claw. At Hamilton’s, they seized four bear teeth, three elk antlers with skulls, and the antlers from a black tail deer mounted on a plaque.

Hollings pleaded guilty to all three cases against him. On Sept. 20, a Polk County circuit judge adjudicated his final case. The total punishment for the three pleas: one year in state prison, more than $40,000 in fines, and a lifetime suspension of his hunting license. Hollings started his sentence last month.

Hamilton awaits his second trial, slated for next April in Polk County, where he faces eight counts related to poaching. In his first trial, he represented himself. The attempt went poorly, especially when he tried to explain away the “stone-cold killer” text message.

During the two-day bench trial in Lincoln County, Hamilton gave a dubious explanation. He testified that the elk was actually roadkill, hit by a van “driven by four or five Mexican guys.”

He claimed Hollings happened upon the carcass and then called Hamilton to drive an hour out to help him load it in his truck. In fact, Hamilton explained, the two were simply taking advantage of the state’s recent passage of new roadkill laws.

Lincoln County Circuit Judge Sheryl Bachart wasn’t convinced.

“You wouldn’t miss what for the world, a roadkill?” Bachart said at sentencing. “You took a picture of your buddy posing with the elk. Actually, you provided the evidence that convicted him. It’s not the first time vanity, I guess, or ego, has sunk somebody’s ship.”

On June 3, Bachart found Hamilton guilty on both of his Lincoln County charges: one count of poaching and another of failing to appear in court.

“I should have got a lawyer,” he muttered to himself during sentencing.

Police may never know how long the poaching went on, or how many animals the crew killed illegally, beyond what was revealed in the scope of their investigation. Andrews says it’s hard to choose which act of theirs was the most egregious. “It was just the constant need for more,” he says.

As for the cougar cub siblings, Andrews theorizes that Hollings first killed the adult female. “The kittens were still hanging out in the same general area, and I think he spotted them basically in a group together and shot all three of them,” Andrews says. “Some of that is speculation, but that’s my theory.”

So far, Lisenby is the only member of the trio to be convicted of a felony poaching charge (Hollings pleaded guilty to felony firearm charges and misdemeanor poaching charges.)

Andrews recalls a conversation he had with a longtime source of his, a logger. That logger told him Lisenby was “the most prolific poacher that he’d ever known, and that we would never catch him,” Andrews says.

“And the fact that I had already been in this career over 10 years at that point, and I had never even met Nic Lisenby, definitely made me think that they’ve gotten away with it for a lot of years,” Andrews says. “And they were gonna continue getting away with it for a lot of years if something didn’t change.”

Correction: A previous version of the big game statistics chart incorrectly listed the number of bears that were illegally harvested in 2020 as 43. The correct number is 13, bringing the 2020 total to 417.