Joe Gilliam, one of the most influential voices in Oregon politics, has been silenced.

For more than two decades, Gilliam, 59, served as president of the Northwest Grocery Association, which counts Fred Meyer, Safeway and Costco among its members. He represented their interests in Salem, battled competitors and earned a reputation as a punishing opponent and loyal friend.

But for the past nine months, WW recently learned, Gilliam has been lying in a vegetative state at an undisclosed care facility in Clark County, Wash. Vigorous and athletic as recently as May 2020, he can now neither move nor speak.

It wasn’t COVID-19 that laid him low.

Nor was it heart disease or a car crash.

It was poison.

Two criminal investigations are pending into Gilliam’s attempted murder, one in Lake Oswego and another in Arizona. Police in both jurisdictions declined to comment.

Both agencies believe, however, that someone close to Gilliam tried to kill him last year with a toxic metal called thallium. And they did so not once, but twice.

His guardian and the judge overseeing his custody are concerned enough that someone will try again that they will not reveal his exact location.

Gilliam’s plight has not previously been reported. A review of documents and interviews with Gilliam’s family, friends and associates yield a tale of a prominent Oregon family beset by tragedy, secrets, broken trust, financial manipulation—and on, two occasions, attempts to kill its most prominent member.

The story would be extraordinary under any circumstances, but the attack on Gilliam comes at a pivotal time—when his organization is trying to pry open Oregon’s tightly controlled market for alcoholic beverages. It’s a crusade Gilliam hoped would be the crowning achievement of his career, and that public employee unions, governments dependent on liquor revenue, and beer and wine distributors all vehemently oppose.

Joe Gilliam became a leader at an early age—but friends say he could also be difficult.

“His personality was always to take things farther than the rest of us,” says his Lake Oswego neighbor Rich Kokesh, who met Gilliam in middle school.

“Joe is a really loyal friend,” says the retired Salem lobbyist Brian Boe, “but he also has a way of really pissing people off.”

A faithful congregant at River West Church in Lake Oswego, Gilliam also loved to spend his evenings in Lake Oswego watering holes like the Dullahan Irish Pub, where his winning smile and considerable charm were on full display.

Gilliam grew up in Happy Valley, the son of Earl “Joe” Gilliam, a Church of God preacher and president of Warner Pacific College. The senior Gilliam was also a friend and spiritual adviser to the late Sen. Mark Hatfield (R-Ore.).

When Joe Gilliam wanted to work in Hawaii during his high school years, friends say, longtime Hatfield chief of staff Gerry Frank arranged a job there. (Frank says he doesn’t recall that.)

A basketball player and standout high jumper at Clackamas High School, Gilliam went on to George Fox, a Christian college in Yamhill County.

Not long after graduating, he landed in Salem, lobbying for the National Federation of Independent Business. A big presence—he was 6-foot-2, 215 pounds—Gilliam was also a quick study, says former state Sen. Jason Atkinson (R-Central Point), able to read people and figure out how to get them what they wanted.

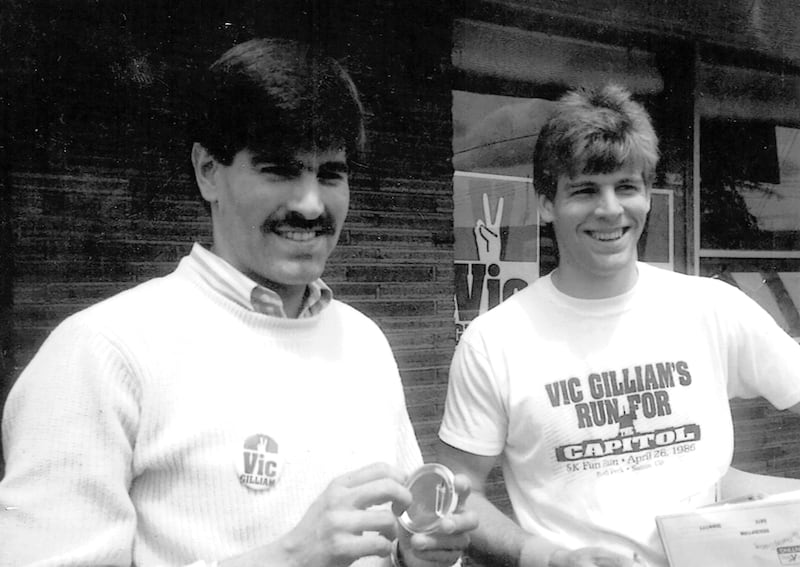

Gilliam’s older brother Vic served five years as a Hatfield aide and later joined Joe in Salem, but not as a lobbyist. Vic Gilliam served five terms in the Oregon House representing Silverton.

In 1999, Joe Gilliam took over leadership of the Northwest Grocery Association, which represents most of the region’s largest grocers. He grew his organization across state lines, into Washington and Idaho, and has efficiently pursued his members’ interests: low taxes, modest wages and minimal regulation.

In 2011, Gilliam leveraged an effort to expand Oregon’s Bottle Bill to get what his members wanted: moving the redemption of deposits on beverage containers outside of stores. It saved stores space, improved sanitation and “was a huge win for the grocery industry,” says Dan Floyd, a former Safeway lobbyist and protégé of Gilliam’s.

Gilliam also helped shape Oregon’s minimum wage law, ensuring that stores in rural areas could pay employees less than stores in the Portland metro area. But his biggest victory came with the defeat of Measure 97, an effort in 2016 by Oregon’s public employee unions to raise billions of dollars in new corporate sales taxes.

Gilliam’s clients were the largest contributors on the “no” side of the most expensive ballot measure campaign in Oregon history. The measure failed, giving the public employee unions their most painful defeat in decades.

“He was very involved in beating Measure 97,” says former Sen. Mark Hass (D-Beaverton). Gilliam subsequently won an exemption for grocers from the massive corporate tax that Hass crafted and which passed in 2019.

Gilliam’s bare-knuckled style won him great admirers and some enemies.

“Sure, Joe’s made some people mad,” says Shawn Miller, a Salem lobbyist who worked with Gilliam for 25 years.

Gilliam’s second ex-wife, Lisa Gilliam, who met him when they were both young lobbyists, says he knew his style and the political positions he took made some people angry.

“But I don’t think this was about politics,” she says. “Joe’s poisoning was a very personal crime.”

Cave Creek, Ariz., is an Old West town of about 6,000 in the Sonoran Desert 45 minutes northeast of Phoenix. Locals ride their horses to bars in what’s been called a “drinking town with a cowboy problem.”

In 2019, Gilliam, a Lake Oswego resident, paid $625,000 for a single-story tan brick house in Cave Creek with a swimming pool and casita on the property. He hoped it would be his retirement home. He earned $400,000 in annual compensation at the grocery association, with regular bonuses on top of that.

In early June 2020, Amanda Dalton, Gilliam’s second-in-command at the grocery association, says Gilliam called her just after returning from Cave Creek.

“He said his legs were numb, he was in tremendous pain—and he was really scared,” Dalton recalls.

Gilliam went first to St. Vincent’s Hospital and then to Legacy Meridian Park as doctors struggled to determine what ailed him. His symptoms worsened, recalls his girlfriend, Christina Marini, 47, and he remained hospitalized for 10 days. Doctors finally diagnosed him with Guillain-Barré syndrome, which causes the body’s immune system to attack the nervous system. He began plasma therapy and medication.

On June 17, Dalton notified the members of the Northwest Grocery Association of Gilliam’s diagnosis.

That same week, Gilliam’s brother Vic died at 66 after a long battle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. Joe Gilliam made his first public appearance since being struck down by the mysterious illness, attending his brother’s funeral. In a wheelchair.

Over the summer of 2020, Gilliam convalesced.

Kokesh, his neighbor, says he and Gilliam used to work out twice a week in Gilliam’s home gym. Now, Gilliam was weak as a kitten.

“He lost 40 or 50 pounds within a matter of a couple of months,” Kokesh says.

By the end of October, Gilliam felt well enough to travel with Marini, to Arizona. Dan Floyd joined them there for Election Day.

“Joe was looking a lot better,” recalls Floyd, who is chief operating officer of the Hood to Coast Relay, a race Gilliam completed four times. “We played golf and I think he was able to walk as much as 2 miles.”

Gilliam’s return to health wouldn’t last.

In mid-November, Gilliam again fell desperately ill. Marini says his condition was worse than before. The pain in his legs and feet prevented him from walking, his gastrointestinal system stopped working, and he vomited frequently.

He resumed plasma therapy. But on Nov. 28, Marini rushed him to the Mayo Clinic hospital in Scottsdale. Gilliam lapsed into a coma and went on life support, she says, and hasn’t spoken since.

On Nov. 30, Dalton notified the Northwest Grocery board that Gilliam was in intensive care.

One week later, Mayo doctors told Marini that Gilliam had a different diagnosis: He was not suffering from Guillain-Barré syndrome—but from thallium poisoning.

The news stunned her. “I remember saying to the doctor, what the hell is thallium?” Marini recalls. “I Googled it and called [Gilliam’s son] Joey right away.”

Thallium sulfate is colorless, odorless and easily dissolved in water. Because it’s extremely rare and difficult to detect, it’s often called “the poisoner’s poison.” The late Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein reportedly used it to eliminate enemies.

Ingesting thallium causes gastrointestinal distress: often vomiting and constipation. Within a day or two, nerve pain in the feet and hands becomes “exquisitely painful,” according to the textbook Clinical Management of Poisoning and Drug Overdose. A victim’s hair begins falling out after about 10 days and is usually gone after a month.

American farmers used thallium to kill rats beginning in the 1920s. In the ‘70s, the U.S. banned it altogether, though the substance is still available on the internet from China and India.

Dr. Robert Hendrickson of the Oregon Poison Center at Oregon Health & Science University says thallium poisoning is vanishingly rare: There were just 49 cases in the whole country in 2019, according to federal figures. Hendrickson says he wouldn’t expect ER doctors to test for it.

“Thallium would be so far down on any list it’s not something anyone would consider,” he says. “Usually the diagnosis is made when all the pieces fit: peripheral neuropathy and people start losing their hair.”

After diagnosing thallium poisoning, Mayo doctors put Gilliam on dialysis to cleanse his blood and prescribed a drug called Prussian blue to help rid his body of the toxic metal.

Joe’s son Joey Gilliam, 32, flew to Arizona and reported the poisoning to police.

“I drove over to Cave Creek and said I just want an officer to take my story down,” he recalls. “A patrol officer was dispatched; at first, he said, ‘This guy’s crazy.’ But he filed his report and that’s when things started to happen.”

After the Mayo Clinic diagnosed thallium poisoning (WW has reviewed records confirming the diagnosis), detectives in Maricopa County identified an initial suspect.

A search warrant served by the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office at Gilliam’s Arizona home in January said deputies were looking for “any container that may contain trace evidence such as a solid, liquid, powder, which may contain a poison, particularly thallium” and “any items of personal property belonging to the suspect, Ronald Smith.”

Marini says police believe she, Smith and another Cave Creek resident and longtime friend of Gilliam’s, the political consultant Tim Mooney, were probably present both times Gilliam was poisoned. (Mooney declined to comment.)

Police aren’t saying why they identified Smith as a suspect, but there are at least a couple of potentially relevant facts:

The first is, he has a previous felony conviction for a bizarre crime.

A decade ago, according to Colorado news accounts, Smith was working as a lobbyist in Denver. Police charged him with placing packages of raw chicken in the air vents of his estranged wife’s home, destroying her piano with a caustic liquid, and taping a mock death notice to her front door.

His ex-wife said he’d sent her threatening texts, including one that said, “I will ruin my life to ruin yours.”

Smith, now 68, pleaded guilty to a felony and a misdemeanor and was sentenced to 90 days in jail and three years’ probation.

Not long after, Gilliam came to Smith’s rescue and brought him to Oregon to work on ballot measure campaigns for the Northwest Grocery Association and later invited him to invest in Gilliam’s Arizona home.

It was in Arizona that three witnesses say Smith and Gilliam clashed bitterly at a restaurant four months before the first alleged poisoning.

Documents WW obtained show Smith had loaned Gilliam $71,000 toward the purchase of Gilliam’s Cave Creek home, in what some observers felt was a deal unfair to Smith. Smith would get to live in the casita on Gilliam’s property for 10 years and would manage the property in Gilliam’s absence.

“The contract was hideous,” says Fred Speck, a longtime friend who was Gilliam’s first boss after college. “I’ve read it. Ron felt it wasn’t fair, but he also felt so beholden to Joe for rescuing him that I think Ron was willing to loan Joe the only money he had left.”

On Jan. 27, 2020, Gilliam, Floyd, Smith, Marini, Mooney and another Portland friend, former AM Northwest host Ken Ackerman, went to a Cave Creek restaurant called Giordano’s Trattoria Romana.

Three of the guests who attended the dinner say Smith and Gilliam argued. The disagreement escalated.

“Ron and Joe were screaming at each other across the table,” Floyd says.

“It got so heated, we all had to leave,” Ackerman adds.

Marini and Floyd say the men argued over travel plans Smith was supposed to have made and Gilliam’s unhappiness with Smith’s management of the property.

On Feb. 17, 2020, Smith emailed Gilliam, asking for his money back in a lump sum. Gilliam first took issue with Smith’s behavior.

“I love you and that won’t change,” Gilliam emailed Smith on Feb. 18. “But since we’re not going to address the restaurant incident face-to-face as men do, we aren’t ok and we won’t be. It’s chicken shit.”

Gilliam then rejected Smith’s request for his money back.

Smith did not respond to requests for comment.

It wouldn’t be long before Lake Oswego police identified another potential suspect: Gilliam’s only son. Although police won’t say why, there are a few reasons they might suspect Joey Gilliam.

First, the younger Gilliam, court records show, has twice been convicted of felony assault, serving time in prison.

And if his father died, he also stood to inherit some of his father’s estate—estimated by Gilliam’s friends at a couple of million dollars. (Joey Gilliam confirms he is a beneficiary of one of his father’s life insurance policies.)

Finally, Joey’s actions as his father lay in a vegetative state raised serious questions.

In June, records show, the care facility pushed to get Joey removed as his father’s legal representative because it claimed he was failing to look out for Gilliam’s interests.

Part of the court’s investigation into his fitness to serve as guardian revealed that between January and June of this year, Joey withdrew a total of about $350,000 from his father’s bank account.

The withdrawals drew the attention of law enforcement.

“The Lake Oswego Police Department has an open and active investigation/case in which Earl ‘Joey’ Gilliam III is suspected of criminal mistreatment I,” Lake Oswego Detective Sgt. James Peterson wrote in a July 19, 2021, statement placed in the court file. “This relates to…management of his father’s funds.”

Peterson went further.

“The Lake Oswego Police Department is also assisting the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office [investigation] into the two attempts at murdering Earl ‘Joe’ Gilliam II by poisoning,” Peterson wrote. “I have confirmed that Earl ‘Joey’ Gilliam is a suspect/person of interest, according to [Maricopa Sheriff’s] Det. TJ Ward.”

Joey Gilliam declined to speak to WW about his father’s bank account but flatly denied any involvement in his father’s poisoning. “Until they solve it, everybody should be a suspect,” he says. “But I had nothing to do with it.”

On Oct. 6, a Clark County judge named a new guardian for Gilliam—his older sister Felicia. Friends left that hearing depressed. “They said Joe is never going to recover,” Floyd says.

Marini, his girlfriend, retains hope. After visiting him Oct. 28, she says she thought he looked better. “I know he’s going to pull out of this,” she says.

As the investigation plods along, mutual suspicions have darkened moods in the overlapping circles of friends and family.

In the absence of an arrest, backbiting and recriminations have chilled communications between Marini and two groups of Gilliam’s friends: his childhood buddies and a circle of political and professional allies.

Some of them feel she has prevented them from being present in his life. COVID has made visiting him difficult, she explains, and she only wants what’s best for Gilliam. “The only thing in this for me is justice for Joe,” she adds.

Marini and Joey Gilliam also no longer communicate. Gilliam’s youngest daughter, Olivia, 22, watches from her college campus in Texas with a feeling of helplessness.

“We’re really frustrated about the lack of progress,” she says.

Meanwhile, Gilliam, who loved climbing mountains like St. Helens, South Sister and Adams as much as he loved eating a steak washed down with an Oregon pinot noir, lies in a nursing home, his body shrunken and locked in paralysis. Although he can now breathe without a ventilator, he cannot speak and his food still comes through a tube. COVID restrictions separate him from the friends who used to surround him.

Those friends are tortured by what happened to Gilliam.

“All he’s doing is existing,” says Dave Martin, a longtime friend who’s still shaken from visiting Gilliam over the summer. “When I was driving away from the nursing home, I thought: ‘Someone fucking did this to him. It wasn’t an accident, it wasn’t a coronary. Some human did this to him, and I can’t live with that.’”

The Ballot Measures

In October, the Northwest Grocery Association filed three ballot initiatives for 2022, in an attempt to break the state’s monopoly on hard liquor and distributors’ stranglehold on wine and beer.

Oregon retains some of the tightest controls on alcoholic beverages in the country. In 2011, Joe Gilliam’s Northwest Grocery Association (which also represents grocers in Washington and Idaho) rode Costco’s checkbook to a new law privatizing liquor sales in Washington.

Efforts in Oregon—which drew stiff opposition from wine and beer distributors—failed in 2014 and 2016.

“It’s a huge, huge issue for the state of Oregon,” says Danelle Romain, executive director of the Oregon Beer & Wine Distributors Association. “It would hurt many thousands of Oregonians and small businesses, and it will disrupt the third-largest source of revenue for the state, which helps support our schools, our health care and our public safety.”

Even from his sickbed last summer, Gilliam was itching for a third shot at grabbing liquor sales for his members in 2022. He joined his deputy Amanda Dalton and others on regular Zoom calls.

“Joe really wanted to get liquor on grocery store shelves,” Dalton says.

The last interview Joe Gilliam gave before he fell ill.

A Most Violent Year

Last year was devastating for the men of the Gilliam family.

Joe Gilliam’s poisonings came during a six-month period when both of his brothers and his father died.

His brothers’ deaths caused Joe Gilliam great pain, while his father’s marked the end of what family and friends say was a tortured relationship.

In 2016, a Clackamas County judge appointed a guardian for Earl “Joe” Gilliam, the family patriarch, after his faculties failed. Joe Gilliam’s younger brother, Steven, who lived in Joshua Tree, Calif., served as guardian, overseeing his father’s money, which court records show was about $1.4 million.

(Joe told friends his father’s money came from Earl Gilliam’s cultivation of the wealthy widow of a former president of the Boeing Airplane Co. In a 2004 court battle over a $20 million trust, Seattle-area charities accused Earl Gilliam of trying to take advantage of the elderly widow.)

On April 15, 2020, Steven Gilliam died of a drug overdose, on his 49th birthday. When Joe Gilliam went to California to settle his brother’s affairs, he would later tell friends, he discovered Steven had spent virtually all of their father’s money.

“He told me there wasn’t enough left to make the next month’s payment for their father’s care,” Gilliam’s protégé Dan Floyd recalls.

Gilliam was despondent, Floyd recalls. But not about the money Steven had squandered—Gilliam told Floyd that money was “tainted.”

Instead, the normally upbeat Gilliam was grieving Steven’s death and the looming death of their brother Vic, who died from ALS on June 17, 2020. (Their father died Oct. 21, 2020, at 91.)

“The three brothers were incredibly close,” Floyd says. “They shared an incredible bond.”

Then in robust health, Gilliam told his friend he feared suffering the same fate that had befallen his older brother, who went from being perhaps the most gregarious lawmaker in Salem to a prisoner in his own motionless body.

“Joe said many times that ALS was the worst thing he could imagine,” Floyd says. “He didn’t want to end up like Vic.”