The night he was sworn in as Portland’s 38th police chief Charles Moose didn’t celebrate. Instead, he went to jail. Alone in his 1991 Ford Taurus, the 39-year-old Harlem native, the youngest chief in Portland’s history, drove to the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem and met with African American prisoners to find out what it means these days to be Black and behind bars.

“They’re worried about what will happen when they’re let loose in the world,” says Moose, the city’s first Black chief, who started meeting with members of a prison-based men’s group, Uhuru Sa Sa, several months ago. “They may be free but they will still be called ex-convicts, ex-this and ex-that. They did the time but the punishment continues.”

Few dispute that after pounding the streets of the city for nearly two decades, Charles Alexander Moose has earned the chance to lead an 1,100-strong police force with an 80 million annual budget.

But the new chief’s decision not to bask in his triumph on the day of his swearing-in but to instead seek out the very population he has spent the bulk of his adult life trying to put away speaks volumes about the man—and the main prominent, yet opposing, aspects of his character.

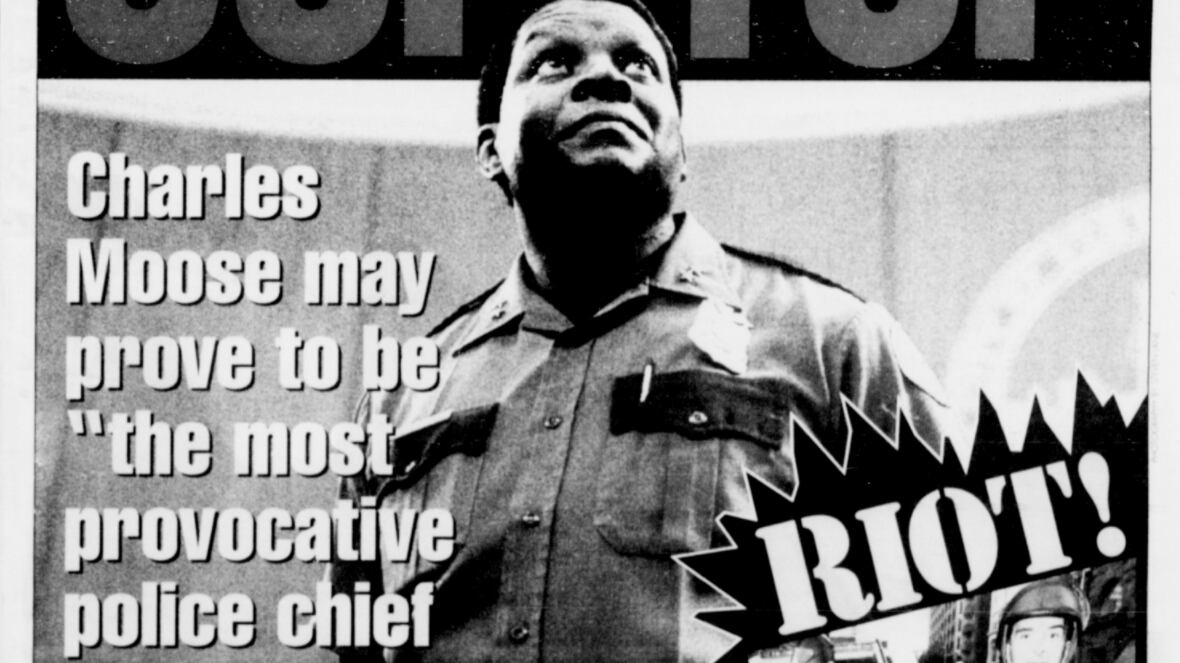

Depending on whom you ask, the former college wrestler who now hangs his bulletproof vest in a corner office on the 15th floor of the Multnomah County Justice Center is diligent or volatile, progressive or militaristic, savvy or naive.

The former North Precinct captain is seen by many as the driving force behind community policing, the cop who not only talked the talk of neighborhood-based public safety but brought the concept to life. At the same time among the rank and file, he’s thought of as “a cop’s cop,” unafraid to let his police force use whatever means necessary within the law to enforce it.

The city’s highest-ranking Black official, Moose is touted as a role model African American yet his marriage to a white woman caused a small uproar in the bureau and may have cost him a job as police chief in Jackson, Miss.

A simple, heartfelt speaker, Moose, by his own account, doesn’t have the eloquent polish of a Tom Potter. Anyone who spends more than a moment conversing with him, however, will detect a political acumen that many politicians strive a lifetime to achieve.

Moose is well aware of the tightrope he must walk in order to make it in a town that polishes off police chiefs as quickly as fine chardonnay. His success or failure will depend on his ability to build unlikely alliances between the police union and the bureau management, Black leaders and white technocrats, civilian review proponents and detectives who scoff at the very notion of citizen investigators. The jury’s still out on his ability to negotiate these worlds, but it is clear that Moose is a cop who defies the stereotype.

“He’s a very passionate person and he doesn’t temper that passion,” says Patrick Donaldson, executive director of the Citizens Crime Commission, a watchdog group composed mainly of businessmen. “It’s going to drive us nuts, that blunt style, but it’s also going to distinguish Charles as the most provocative chief in recent history.”

Born in Harlem in 1953 as the middle child of a high school science teacher and a nurse, Charles Moose doesn’t recall much about New York City. When Moose was a year old, his father completed a master’s degree in biology at Columbia University, and the family left Manhattan for Lexington, NC., fleeing the rising crime that threatened their two sons, David and Charles, and a daughter on the way, Dorothy Louise.

Moose was a jock in high school, rather straitlaced, and spent much of his time in college training and competing on the wrestling team.

A college deferment kept Moose out of the military, until many years later, when he voluntarily joined the Oregon Air National Guard in 1987. Though he attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the early 1970s at the peak of the Vietnam War, Moose’s activism was minimal. “We watched the war on television,” he says.

As far as race relations went, Moose favored integration. “We wanted to go to the white schools, to the white universities, we wanted to be treated fair.”’ He spoke of his thrill when Stokely Carmichael came to the university to speak.

During his senior year, Moose took a class, “Who Will Police the Police,” that would eventually lead him into law enforcement. Before graduation, the history major received a job offer from then-Portland Police Chief Bruce Baker. Moose packed up his new Fiat in May 1975 and drove from North Carolina to Oregon, never imagining that the job would become a career.

Dorothy Moose followed her brother to Portland and today is a nurse at Bess Kaiser Medical Center. The two remain close, in large part because of the rest of the family’s bleak history. His mother died when Charles was 16, and his father died of lung cancer in 1983. Before that, Moose’s older brother disappeared, got hooked on drugs and “wound up in a one-room flophouse in LA,” where he died of tuberculosis, Moose says.

Moose divorced his first wife, Linder, in 1987 and has one son, David, now 13. Though he lives in Northeast Portland with his mother and stepsister, David has neither seen nor spoken to his father in more than a year, largely because of bitter fights between his parents.

Moose tries to deal with the loss in a positive light, struggling with the fact that David did not attend his swearing in ceremony.

“At least mv son didn’t read about me going to jail,” Moose says. “He read about me doing well.”

If there’s one accomplishment that stands out about Moose, it’s his tireless campaign to give definition to the cliche “community policing,” to link citizens and cops in a partnership for public safety.

His successes-assigning cops to attend specific neighborhood association meetings in order to connect with the community, and his campaign against drugs and gangs at the Iris Court complex last spring (the subject of his doctoral thesis)—has led North Precinct sergeant Jeff Barker to speculate that Moose will be snatched out of Portland to lead a larger urban police department within five years.

“North Precinct is community policing,” says Mayor Vera Katz. “And Charles, as captain, pushed that agenda.”

Beruti Artharee, president of the Empire Security Service on Northeast 7th Avenue and Alberta Street, says Moose has helped Northeast businesses and community groups thrive over the years by making it safer for them to exist.

Artharee met Moose four years ago when Empire Security Guards patrolled the state Department of Human Resources building.

“We had a real problem with drug dealing and prostitution on the premises,” Artharee said. Moose was instrumental in drawing together building managers, the assistant district attorney and beat cops from North Precinct to crack down on crime so Artharee could fulfill his contract.

“It’s a great thing that has happened.” says state Rep. Avel Gordly of Moose’s appointment. “Charles can truly make an impact here. This isn’t LA or Cleveland or Atlanta or New York, where the social conditions have been allowed to decay so that it’s utterly hopeless. That’s not true in Portland. Yet.”

“It is Moose’s reputation for patience and his caring style on the beat that makes his penchant for exploding on the job seem out of character. In fact, his temper nearly derailed his bid for chief, forcing a lengthy meeting between Moose and Katz’s executive assistant, Sam Adams, on the subject.

“He’s a time bomb,” says Penny Harrington, the first police chief under Mayor Bud Clark and now special assistant to the director of the Department of Investigations for the California State Bar. “He’s going to lose his temper the first time Vera makes a decision he doesn’t like.”

Harrington isn’t the only observer who’s raised the specter of Moose’s short fuse. In fact, Moose’s personnel record mentions a 1987 incident in which Moose, then a lieutenant, yelled at a woman crime prevention officer, telling her to “fuck off " after she questioned his actions. He received a written reprimand from the bureau. Disciplinary action that falls short of demotion or dismissal can be purged from an officer’s file after five years if there are no repeat offenses. However, Moose chose to leave the damning internal investigations report in his file, “because I think I need to remind myself that that was very stupid.

“I’ve done things in my past,” he adds, “that would say, if you always just base your judgment of me on what I did that day, then I would never become anything.”

That might suggest that Moose’s bad temper has been eliminated, or at least cooled. Harrington’s sister Roberta Webber, who replaced Moose as captain at North Precinct and was recently appointed to serve as his deputy chief, concurs. “He’s grown,” she says.

“He really has dealt with that issue,” Webber adds. “And gone on to do so much good.”

The extraordinary ascension of Charles Moose in a police force that is just over 3 percent Black points to another aspect of his complex character.

When Moose joined the bureau in 1975 there were a total of 10 Black cops. Each time he was promoted, the appellation “first Black” was linked to Moose’s name. He started working undercover, buying dope for the bureau’s drugs and vice division. As he rose through the ranks—to sergeant in 1981, lieutenant in 1984, captain in 1991, and to deputy chief last year—he broke the color barrier every time.

Accused by some officers of holding Black cops to a higher standard, Moose says, in the current climate, he has no other choice.

“We all hold ourselves to a higher standard,” he says, looking as he does, straight and deeply into the eyes of the person to whom he is speaking. “We have to.”

Because of his political consciousness about what it means to be a Black man in the United States, it’s all the more painful when he is charged with forsaking “the community.”

In the mid-80s while he was still married to his first wife, Moose started having an affair with Sandra Herman, a white woman whom he had met in graduate school at Portland State University. They married in 1988.

“It was a scandal,” says Herman who now attends law school at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma Wash. “Many African American friends were hurt. It’s a loyalty issue that runs real deep.”

Over the years, the acceptance accorded her and Moose has increased. However, residual anger remains. The day before Moose was sworn in as chief, Herman says, an African American friend of hers got a call saying it should have been Linder standing with the new chief before the cheering crowd at City Hall, not Sandra. “This is America, this is Oregon,” says Rep. Gordly who worked with both Sandra and Charles. “We still have a problem with race—it’s always an issue.”

Indeed. Two years ago, Moose was one of three top candidates vying for the job of police chief in Jackson Miss. He was considered a front runner, according to local press reports. Then, at an evening show and tell, candidates were asked to introduce their families to the mayor’s blue ribbon selection committee.

The weekly Jackson Advocate quoted one committee member, Ponto Downing as saying, “Moose walked in with a blonde-haired blue-eyed, white wife that killed any chances he had of becoming police chief here.”

Sandra Herman-Moose, born in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, and reared in Drain Ore., by Southern Baptist loggers, was not a woman who allows a racial slur to slide. After Charles was eliminated as a candidate in Jackson, she called a lawyer at the Southern Poverty Law Center, a Montgomery. Ala.-based organization that takes on discrimination cases.

“We talked, and the lawyer said to me, ‘I can get you that job.’” Charles Moose recalls. “But frankly, after the whole situation, I didn’t want that job.”

Even more hurtful than the abuse in Jackson were feelings that emerged at home.

The Jackson newspaper quoted Portland officer Victoria Wade, who said that Moose was in good standing with “Portland’s high ranking whites” but that he had little support among Blacks. Wade later apologized to Moose and now maintains that she never made the statement. “I think Charles Moose is a great man, and he will be a great chief,” she says, refusing to comment further.

The biggest contradiction about Charles Moose also involves Sandy Herman, but it has nothing to do with the color of her skin.

From 1983 until 1990, Herman was the staff liaison to the bureau’s Police Internal Investigations Auditing Committee, or PIIAC. Appointed by the City Council, PIIAC members review complaints of police misconduct but have little power to act. By the time she quit her post, after winning a sexual harassment and job stress suit against the city in which she agreed never to work in City Hall again, Herman had become one of PIIAC’s and the cop shop’s most visible critics. She pointed out, correctly, that the committee was impotent and argued that it should be replaced by an independent civilian review board with both the power to review serious cases of officer misconduct and the authority to discipline cops who cross the line.

For many police officers, the prospect of an independent body of amateurs determining cops fates is the equivalent of a firing squad. For this reason Sandv Herman is perceived within the bureau as anti-cop. That she’s married to the man now running the bureau is unsettling for some on the beat.

In fact, one source says Moose got a call from a member of the mayor’s search committee four weeks before Katz announced the chiefs appointment. The committee member had called to discuss Moose’s wife.

“Charles, do you think you can shut her up for a few weeks?” the committee member asked. “She may hurt your chances.”

Despite the caller’s good intentions, he clearly didn’t know who he was dealing with. “When I hear someone say that, it’s the end of the conversation, because I don’t shut anybody up,” Moose savs. “It’s not very democratic, not very American.” And so Herman spoke out. At a City Council meeting, just weeks before Moose was hired as chief, she called for the abolition of PIIAC and demanded an independent citizen review panel. She characterized the current committee as a “low-budget operation” and an “insult” to Portlanders. Moose’s take on the issue is much less radical. He’s not interested in abolishing PIIAC, although he advocates some change, such as establishing a setting outside the Justice Center in which citizens can file complaints. (Citizens now have to enter the cops’ home base to level charges.) Unlike his wife, Moose continues to support the use of detectives, not citizens, as investigators, and the police chief and mayor as disciplinarians.

Herman and Moose part ways on the issue and have debated for years how much power citizens should hold when it comes to monitoring and disciplining police.

“It’s kind of a Bill and Hillary thing,” savs Sam Brooks, a Northeast Portland businessman who has known the couple for years. “Just because they’re spouses, it doesn’t mean one is a duplicate of the other.”