Ashton Simpson says the record number of people killed this year while crossing a Portland street isn’t just about the speed and scale of car traffic. It’s a symptom of this city’s housing crisis.

Simpson, executive director of the nonprofit Oregon Walks and a candidate for Metro Council, says he’s observed more people living in tent camps along the sides of busy arterial roads like Northeast 122nd Avenue.

“They’re just trying to get to the corner store right across from their camp, and there’s no clear crossing,” Simpson tells WW. “What happens when someone’s having a mental breakdown at 3 in the morning and they get struck on [Interstate] 84? Because they’re right there.”

His observation provides a new angle on what is now a dispiritingly familiar story: an increasing number of people killed in traffic.

On Nov. 24—the night before Thanksgiving—a person died walking across Northeast Marine Drive and another died at the wheel along Northeast Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Police logged those as the 60th and 61st traffic deaths of the year—surpassing the 59 fatalities in 1996, the record since Portland started keeping detailed figures.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation’s tally is lower—56 deaths—because the National Highway Safety Board doesn’t count deaths in parking lots or suicides. But Portland is certainly on pace to eclipse the quarter-century-old record.

Many saw the bleak milestone coming. Last year’s traffic death toll—54—was the second highest of the 21st century, and 2019 was close behind. In March, Simpson and his Oregon Walks co-founder Scott Kocher blamed the steady increase on drivers going too fast on roads that are too wide, inadequately lit and lacking crosswalks—and Portland officials not acting aggressively enough to slow them down (“You’re Driving Too Damn Fast,” WW, March 17, 2021).

For city leaders, the record marks another chapter in the failures of an ambitious 2016 policy, called Vision Zero, which included a goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2025. By year’s end, the city will have sunk $185 million into the campaign.

Instead, deaths have increased, regardless of conditions.

In 2020, when a pandemic emptied the roads and drivers often flew down highways at more than 100 miles an hour? Traffic deaths went up. In 2021, when enough people returned to their routines that rush hour resumed? Traffic deaths again went up.

Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, who oversees the Portland Bureau of Transportation, calls the numbers a “devastating development.” Hardesty says she’s grappling with the problem by taking local control of 82nd Avenue to slow its drivers, making rapid safety improvements to the most dangerous roads, and seeking a change in state law to add more speed cameras.

“Vision Zero is a goal and a work in progress,” she says. “Had we not made the investments we did in recent years, I believe the traffic fatalities would be far worse on PBOT-controlled roads. That doesn’t take away from the unacceptable number of tragedies that have occurred on our streets this year. My priority will continue to be securing investments on high-crash corridors where most traffic fatalities are occurring.”

Meanwhile, at a Nov. 30 press conference, Portland Police Bureau Sgt. Ty Engstrom blamed the death toll on a gutting of the bureau’s traffic division. “Right now we’re at 62 fatalities, and that’s nowhere near zero,” he said, including a Nov. 21 hit-and-run following a knife fight in a parking lot. “I’m tired of seeing dead bodies.”

What makes the trend more frustrating to policymakers is that the deaths are happening exactly where the city’s Cassandras expected.

A review by WW of the 61 deaths tallied by the Portland Police Bureau shows that the deaths in 2021 fit into patterns previously identified about who dies and where. Here’s what we found.

A few high-traffic roads are the scenes of more than half the deaths.

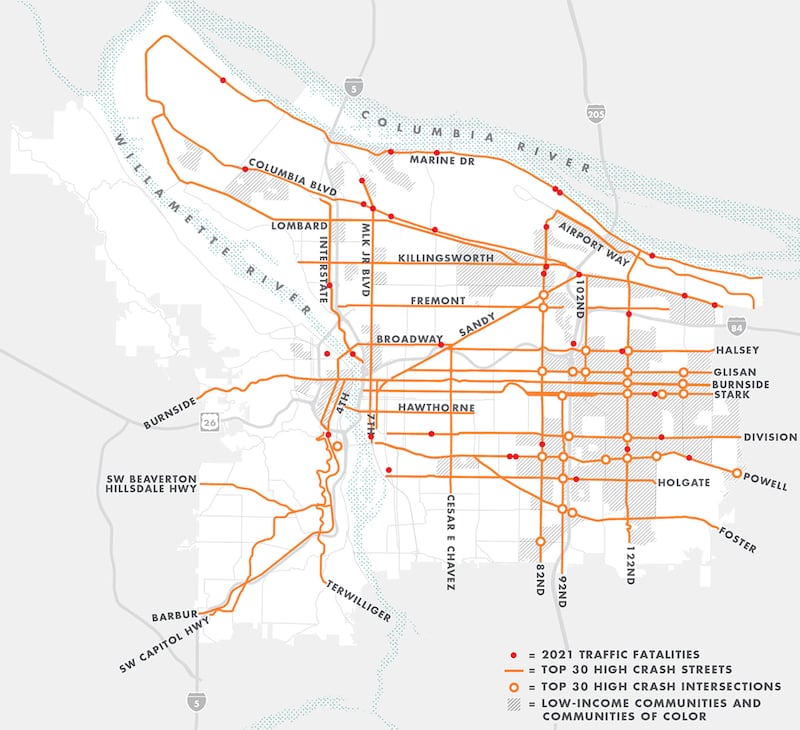

A Portland Bureau of Transportation study released earlier this year shows that 56% of traffic deaths in 2020 took place on just 8% of the city’s roads. City engineers have dubbed those streets “high-crash corridors,” and they’ve poured much of the Vision Zero money into new lighting and crosswalks on these arterials.

But in 2021, WW found, the ratio remained unchanged: 59% of deaths occurred on that same 8% of blacktop. That means at least 36 of the 61 deaths occurred on urban highways, including Marine Drive, Powell Boulevard and 82nd Avenue.

Dylan Rivera, a spokesman for PBOT, says 27 of the deaths this year occurred on interstates and highways controlled by the Oregon Department of Transportation.

Kocher says those high-crash corridors, shown in orange on the map below, are designed in ways that guarantee motorists will drive too fast.

“What you see time and time again is long straightaways with multiple lanes,” he says. “If you’ve got a 3,000-foot straightaway with a 12- or 13-foot travel lane, it’s very hard to ensure that everybody driving a car or truck on that roadway is going to be driving at a safe speed and that people will be able to cross.”

Pedestrians make up a large share of deaths.

Twenty-six deaths—or 42%—were people walking when they were killed. The Portland Police Bureau’s traffic division says it’s the highest number of pedestrian deaths since 1972. (Portland saw its first death on a scooter in April—and since then had two more.)

Simpson sees a correlation between people living outdoors and dying while walking. “We can’t have folks just living in the streets like this,” he says. “We claim to be this city of progressive values, but we’re OK with people, with kids too, with families living outside, being impacted by the flumes and weather? For me, it’s unacceptable.”

Many of the deaths occurred in outer East Portland.

For years, Portland traffic deaths have skewed heavily eastward. WW revealed in March that half of the 48 pedestrians killed between 2017 and 2019 died east of 82nd Avenue. (During that same period, not a single person died while walking in Northwest Portland.)

This year, 23 of Portland’s traffic deaths—more than a third—occurred in outer East Portland. “Crashes are disproportionately in East Portland,” says Kocher, “and they are disproportionately in the big streets.”

That means the neighborhoods where people most often die in traffic are also the communities where people were most often being murdered as Portland broke its all-time homicide record this year, with 79.