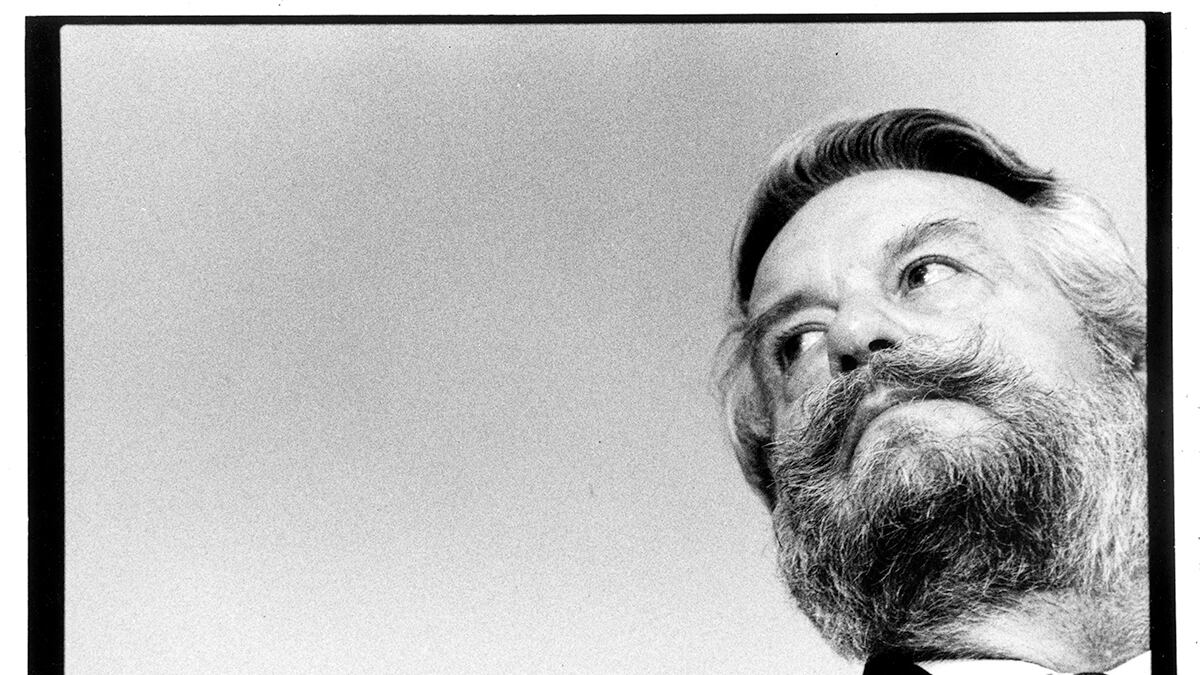

When John Elwood “Bud” Clark Jr. died at 90 last week, Portland lost a leader who embodied what voters often say they want: a political outsider who ran his the city the way he ran his small business, the Goose Hollow Inn.

In his eight years as mayor (1985 to 1993), he’d talk to anybody anytime and treated the city’s challenges like a grease fire in the Goose’s kitchen: He rolled up his sleeves and took action.

Clark won national attention for a 1978 poster in which he opened his trench coat—presumably wearing nothing underneath—to flash a bronze statue. The caption: “Expose yourself to art.” A first-time candidate, he stunned incumbent Mayor Frank Ivancie in the May 1984 primary, ushering in a new, progressive era in the city’s history.

Word of Clark’s death arrived a few hours before our Feb. 2 issue went to press. A week later, here are snapshots of Clark in the words of old friends.

HE FEARED NOBODY.

When Ivancie produced a campaign ad late in the 1984 campaign showing himself talking to Portlanders from a helicopter, Tim Hibbitts, the young pollster advising the upstart Clark, thought his candidate just might win.

Ivancie, a dour favorite of the downtown business set and blue-collar North Portland, didn’t connect with the average Portlander. He also never took Clark seriously, for some good reasons. In the campaign’s first poll, Clark trailed Ivancie 49% to 14%.

But as Ivancie snoozed, Clark put in 16-hour days and tapped the progressive wave sweeping Portland. Some wealthy candidates finance their own campaigns. Clark, a father of four trying to keep his tavern afloat as he canvassed the city, took out a second mortgage on his home to pay for lawn signs and ads. “He was absolutely committed,” Hibbitts says.

Voters noticed. “I think it was a combination of Ivancie’s arrogance and Bud’s effervescence,” Hibbitts says. “The more people knew him, the more they liked him.”

HE SOLVED PROBLEMS.

“The thing about working for Bud was that the man was fearless,” says Chris Tobkin, his first chief of staff.

In 1985, the Amalagamated Transit Union, which represented bus drivers, deadlocked with TriMet after months of contract negotiations. Transit officials came to City Hall to tell Clark a strike was imminent and inevitable. “He said, ‘There’s no way you’re going to let this happen,’” Tobkin recalls. The city was digging out from a crushing recession, and officials feared a work stoppage would hobble downtown.

Clark asked Gov. Vic Atiyeh, who appointed the TriMet board, to intervene. Atiyeh declined. Clark then reached out to Ed Whelan, the retired AFL-CIO boss and most respected man in Oregon labor. Whelan agreed to help, but only under conditions of total secrecy. Clark sequestered ATU and Whelan at the Hilton Hotel for three days. Strike averted.

“I hate it when people think of Bud being best known for the ‘expose yourself to art’ poster,” Tobkin says. “That’s just wrong. Bud cared more about the city than anything else. He didn’t have any power over any of those people, but he jumped in where nobody else would and he got a settlement—that’s the kind of mayor he was.”

HE WAS A REAL OREGONIAN.

Mayoral aide Chuck Duffy recalls that when a question arose about the city’s water supply, Clark and about 20 others journeyed to the source, the Little Sandy River in the Bull Run Watershed. Clark picked up Duffy that morning with his canoe atop his car.

When they arrived at the river, Water Bureau officials had procured a fleet of large rubber rafts and a mound of safety equipment. One official, already in his life jacket, approached the mayor. “When I saw that canoe, I thought you were going to try to take it down the river,” Duffy recalls the man saying.

“What the hell do think I brought it for?” Clark replied.

He pushed off in the boat by himself, without a paddle or a life jacket.

“When we came to rapids, he’d squat down and put the pole parallel to the water to steady himself,” Duffy says. “He was a hell of a guy.”

HE NEVER ASPIRED TO A PROMOTION.

For many politicians, the only antidote for ambition is embalming fluid.

Julie Williamson, the veteran political consultant who ran Clark’s 1988 reelection campaign, recalls he was the rarest of elected officials—he had no interest in higher office. “He didn’t care about politics,” she says. “He cared about Portland.”

Williamson worked to rein in some of the habits that she thought undermined Clark’s gravitas, such as his favorite expressions, “Tits up,” or “Whoop, whoop!” the mating call of a male guinea pig.

“I had to tell him he couldn’t wear his lederhosen when he went to a convention,” she says. “He said, ‘I don’t care if you run naked down Northwest 23rd; why do you care whether I show my legs?’”

Williamson wanted voters to focus on Clark’s intellect, often overshadowed by his flamboyance. “He was much smarter than some people thought,” she says, adding that Clark’s style was to help others achieve their goals and not seek credit for himself.

But his greatest skill was connecting with people. “He was extremely tolerant and extremely inclusive,” Williamson says. “Bud and [his wife] Sigrid would close the Goose on Thanksgiving and open their house so all of the people who halfway lived at the Goose would come over for dinner.”