For decades, 122nd Avenue has gone nowhere fast.

A drive down this north-south thoroughfare displays the effects of City Hall’s neglect of East Portland. The vista is dotted with used car dealerships, lottery delis and chain restaurants. It’s one of the roads where Portlanders most frequently die in traffic and runs through the neighborhoods where they are most likely to be shot.

And it’s where the city’s economic development arm, Prosper Portland, is being offered a chance at renewed relevance and perhaps to revive its faltering finances.

Documents and interviews show East Portland community groups have sought and held preliminary conversations with Prosper Portland about launching a new tax increment financing district there, also known as an urban renewal area.

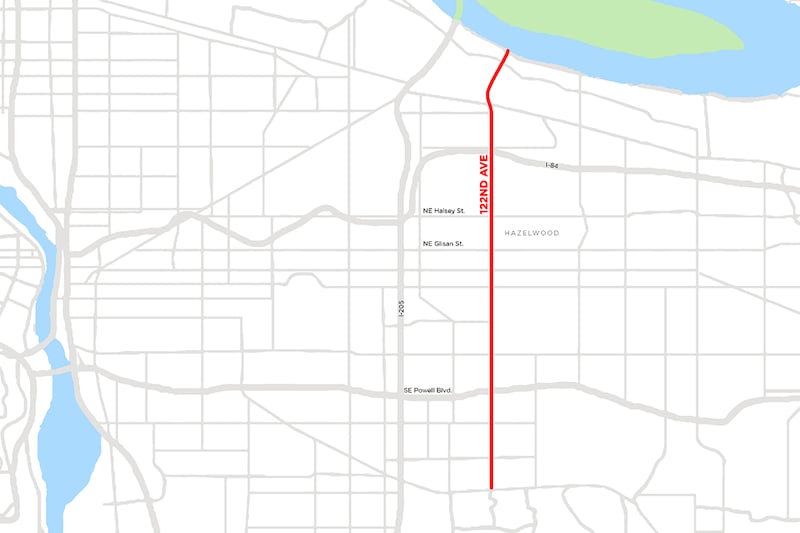

A map obtained by WW shows the area under consideration includes the East Portland neighborhoods of Hazelwood, Russell, Parkrose Heights, Maywood Park and Argay, with 122nd Avenue running down the center.

Urban renewal is the same tool Prosper Portland (formerly known as the Portland Development Commission) used to create the Pearl District and South Waterfront, and to make way for a new light rail line through North Portland.

But it’s also a method many critics say has done more harm than good. Urban renewal is now inextricably linked to the gentrification that exiled Portland’s poorest residents—many of them Black—to the city’s edges.

Places like 122nd Avenue.

“The legacy of [urban renewal areas] is displacement, gentrification, and creating neighborhoods that serve the next generation of folks coming in at the expense of folks already living there,” says Callie Riley, anti-displacement coalition manager for the racial justice nonprofit Unite Oregon. “In North and Northeast Portland, it’s been disruption and destruction of predominantly Black neighborhoods.”

That means Prosper’s discussions about renewing 122nd Avenue are delicate: The agency has met with affordable housing agencies, neighborhood associations, and social justice organizations—that is, the groups that largely represent the communities that have historically been displaced, gentrified and priced out of TIF districts starting back in the 1970s.

Prosper Portland says the conversations are being led by the community, and Prosper has “provided technical information as requested.”

“Should community interest and City Council support align, we would envision exploring a potential East PDX TIF district prioritizing anti-displacement and equitable development,” the agency tells WW.

East Portland is in dire need of dollars from the city, which has underinvested there for decades.

Stakeholders see a TIF district as one way to get much-needed funding, but insist that urban renewal be done differently than before. And some East Portland residents remain deeply skeptical.

Nick Sauvie, executive director of the housing nonprofit Rose CDC, describes the feedback from stakeholders in a meeting last month as “all over the place.”

“Some people said they’d really like that, and there were some that were like, ‘Over my dead body,’” Sauvie says. “Prosper is going to put on a full-court press to get new areas to replace the expiring districts.” (Prosper says it’s merely responding to community interest.)

It might seem quaint now, given Portland’s recent struggles, but there was a time, not two decades ago, when the location and size of urban renewal areas were among the most hotly debated topics at City Hall.

Tax increment financing is a migraine-inducing topic, but the basic concept is this: Prosper draws a line around a neighborhood it considers blighted. It borrows against future property tax revenues in the district. For the next several decades, excess property taxes over the base revenue set when the district was formed stay in the neighborhood. Instead of going to the general fund, the tax dollars must be invested within the district.

Prosper gets a cut of the money raised by the TIF districts, but they have a limited lifetime. That means the agency must find places it can start anew, or face running out of funds. (Prosper tells WW new TIF districts alone cannot solve the money problem “in the near term.”)

A receptive audience in East Portland could be a godsend for Prosper, which has struggled to create any other major revenue sources.

All of Prosper’s 10 remaining districts are close to sunsetting. The last time Prosper launched a new urban renewal area was in 2001.

The City Budget Office called the sunsetting of districts and debt proceeds—expected to reach zero in 2025—the “TIF Cliff” in a recent budget document.

Prosper Portland, once the swashbuckling envy of other city bureaus, currently has 87 employees, a 60% decrease from 2009.

In short, Prosper is in danger of disappearing.

In 2017, the agency laid out a new funding blueprint to stay afloat, with an emphasis on generating income from real estate. But some of its biggest development projects since then—including the 14-acre post office site, which is part of the larger Broadway Corridor, and Zidell Yards along the South Waterfront—have all fallen through.

The interest expressed by East Portland stakeholders in a new TIF district should be welcome news.

“There is very early interest for exploring an East PDX TIF district, and primarily these are community-led conversations that we’ve only just started engaging in,” says Shea Flaherty Betin, Prosper’s director of economic development.

The boundaries of such a district are not yet clear. Hazelwood is smack dab in the middle, but the circle also contains parts of several other neighborhoods in Northeast and Southeast (see map below).

Gateway Regional Center and Lents Town Center, Prosper’s two previous East Portland urban renewal areas, have received mixed reviews.

A 2020 city audit of the Lents district chastised Prosper for not tracking its progress more closely, and found that property values there rose drastically while BIPOC homeownership dropped.

Potential stakeholders in East Portland want to have a strong say in which projects would receive funds in the district, a point that could cause tension down the line.

Andy Miller, director of the affordable housing nonprofit Human Solutions, says Prosper has a chance to demonstrate it’s a changed agency.

“We’d like to see them prove that,” Miller says, “by delivering on the next set of TIF districts to ensure that the power of decision making is held by the people who have historically least benefited from their decisions.”

Similarly, Duncan Hwang of the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon says his nonprofit is “open to having that conversation” with Prosper if community groups have a strong say in what gets funded.

They’re partly looking to an initiative between Prosper and community groups in the Cully neighborhood as a new model to emulate: Groups there have led a plan for a larger TIF district in Cully for four years now, emphasizing the community’s input. (Any TIF district must ultimately be approved first by Prosper’s board and then the City Council.)

Others, like Riley of Unite Oregon, think urban renewal districts should be a thing of the past: “I think it’s a bad mechanism that can’t be made better.”

For Sabrina Wilson, executive director of the Rosewood Initiative, a community resource center, the preliminary question before more robust discussion starts is simple: Can Prosper and East Portland come to an agreement about who should benefit from the district?

“First we need to talk about what issues we’re looking to improve in East Portland as a whole,” Wilson says. “If TIF doesn’t address the concerns we have, we shouldn’t put our energy there.”

This article was published with support from the Jackson Foundation, whose mission is: “To promote the welfare of the public of the City of Portland or the State of Oregon, or both.”