Portland police officer Chris Burley was stationed at the sound truck parked atop a Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office building as a protest swelled along East Burnside Street below. It was a Monday night in September 2020, weeks after the departure of federal agents who faced off with the “Wall of Moms” and tear-gassed the mayor in downtown Portland.

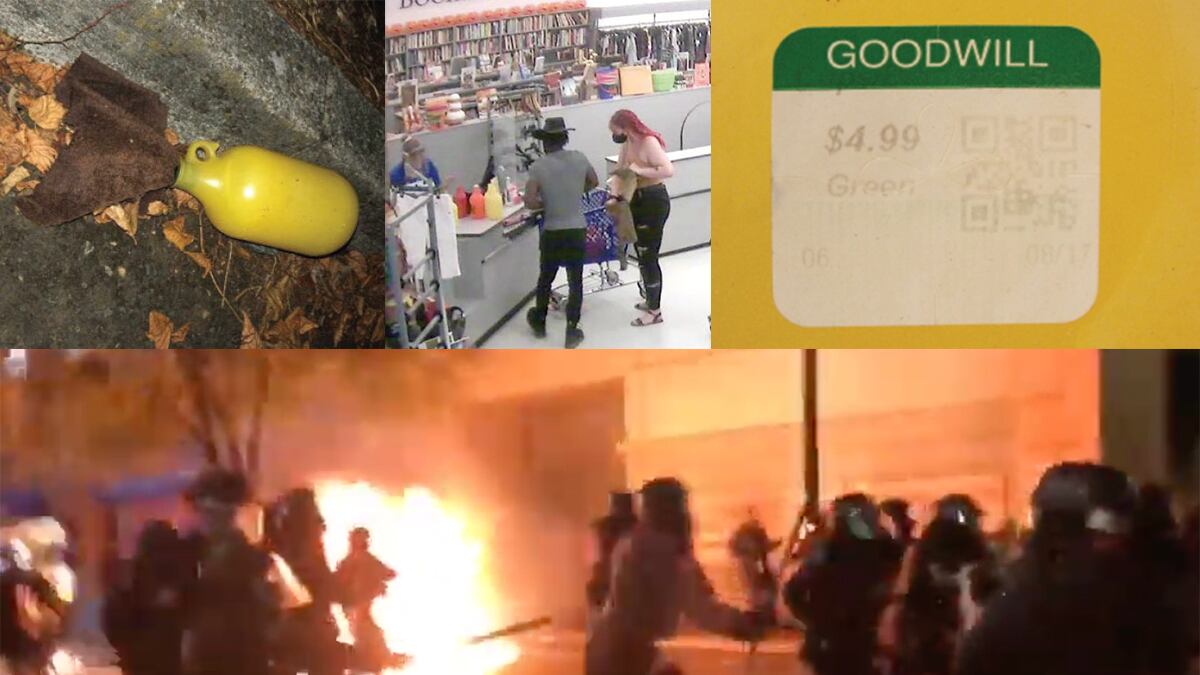

The feds were gone, but the protests were not. Burley looked on as a burning object flew through the air like a shooting star and landed within 15 feet of the truck. He exited the sound truck and inspected the yellow glass bottle, which was still intact. It resembled a beer growler, save for the yellowish-green liquid inside and a burnt rag stuffed in its mouth.

On the bottom of the Molotov cocktail bottle: a price tag from the Goodwill store in McMinnville. About two weeks earlier, after another protest, police had found a baseball bat with a price sticker from the same Goodwill. The store’s security footage from Sept. 4, 2020, showed a young couple purchasing baseball bats and growlers.

From the footage, police recognized the man who wore a black cowboy hat and jeans and was far from his home in Marion, Ind.: 23-year-old Malik Muhammad, a U.S. Army veteran.

“Muhammad’s trip to Portland does not appear to be an isolated event,” federal prosecutors later wrote.

Within weeks of purchasing the baseball bats and growlers in McMinnville, Muhammad was arrested at another Portland protest, dubbed the “Indigenous Peoples Day of Rage.” Plainclothes FBI agents alleged they witnessed Muhammad smash windows at the Oregon Historical Society, Portland State University and a Ben Bridge Jeweler using a baton. Muhammad fled as police tried to arrest him. After a foot chase, police detained Muhammad, who allegedly carried a 9 mm pistol and 30 rounds of ammunition.

In the five-odd weeks that transpired between the Goodwill shopping excursion and his arrest, state and federal prosecutors allege, Muhammad attended four Portland protests. During some of those events, he threw Molotov cocktails toward police—including one that “seriously burned” a protester, and another that caught an officer’s pant leg on fire—and handed out baseball bats to incite property damage, prosecutors say.

Now, a year and a half later, Muhammad faces what appears to be the longest sentence handed down to a Portland protester after the 2020 uprising: 10 years in prison.

He pleaded guilty to two counts of unlawful possession of a destructive device in federal court on March 28, and 14 charges in state court on Tuesday for attempted murder, assault, unlawful manufacture of a destructive device and more. A judge sentenced him to 10 years in prison March 29.

During the sentencing hearing, senior deputy district attorney Nathan Vasquez said it was fortunate that the Molotov cocktail that landed near PPB’s sound truck did not explode. “I can only say that good luck and fortune intervened and that for some reason it didn’t break and didn’t explode into fire,” Vasquez said. “It was that piece of evidence that really, in large part, was the undoing for Mr. Muhammad, as much evidence was obtained from that.”

It would be tempting to make Muhammad into a parable of the rise and fall of the Portland protests, or the extremes of anarchist protesters. Indeed, he appears to represent the prototype of the “outside agitator” that police lamented in 2020.

“I think it’s feeding into the overall narrative that they know people are trying to swallow, which is that outside agitators were really the problem in the summer of 2020 protests and that there’s no need to change anything here,” says Juan Chavez, a Portland civil rights lawyer. “It was this bogeyman that they had to create because they knew that people were in mass support for the movement for Black lives.”

But a review of hundreds of pages of court documents suggests Muhammad’s case was an outlier, largely because he has little connection to the region.

In fact, prosecutors say he traveled to Portland for the sole purpose of wreaking havoc at protests.

“The defendant traveled to the Portland metro area for the specific purpose of engaging in the multiple criminal episodes and behavior that this case is based on,” Vasquez wrote in a May 2021 filing. “As he has shown time and time again, he will go to extreme lengths to exert his extreme ideology, up to and including building fire bombs and attempting to murder police officers.”

Born and raised in Chicago, Muhammad enlisted in the U.S. Army in 2015, when he was approximately 18 years old. He sustained injuries in the Army, leaving him partially disabled, according to court filings. Three years after enlisting, in 2018, he was honorably discharged.

If the story prosecutors tell is correct, any reverence Muhammad felt for the U.S. government was diminished or perhaps abandoned within a few years of leaving the Army.

When police searched Muhammad’s travel trailer in October 2020, they found several firearms, including an AR-15 rifle owned by a man in Indianapolis.

“[The witness] explained that while living in Indiana, he met Muhammad in the months prior to his travel to Portland,” federal prosecutors wrote in a November 2021 filing. “He explained that Muhammad was attempting to recruit people to engage in violent activities, including an armed forceful takeover of a radio or television station.”

The man described Muhammad as “a communist revolutionary who was attempting to gather people with firearms to engage in acts of violence,” according to the filing.

Two weeks before arriving in Portland, in August 2020, Muhammad allegedly traveled to Louisville, Ky., with five associates. The purpose of the weekend trip, prosecutors allege, was to “conduct firearms and tactical support.”

“Muhammad’s intent since he left Indiana has been clear,” federal prosecutors wrote. “He wanted to commit violent acts against law enforcement and advocate others do so as well.”

It’s also worth noting that one of the Portland protests in which prosecutors say Muhammad threw a Molotov cocktail occurred Sept. 23, 2020—the same day a grand jury declined to bring charges against two Louisville police officers in the shooting death of Breonna Taylor.

Prosecutors claim that Muhammad’s actions “reveal a person driven to violence.”

“He put the entire community—a community he is not even a part of—at risk while specifically targeting law enforcement,” federal prosecutors wrote late last year.

Not everyone in Portland viewed him as an outsider. In late May, weeks after police extradited Muhammad from Indianapolis to Portland, he was out of jail again—for about 48 hours.

A Multnomah County circuit judge had set Muhammad’s bail at $2,125,000. Then, on May 26, a community organization called the Portland Freedom Fund posted the requisite 10% bail amount—$212,500—and Muhammad was out.

His freedom was short-lived. Two days later, on May 28, the feds arrested him on their own warrant.

Court records do not provide any explanation directly from Muhammad as to his motivation. That makes it difficult to assess what role his mental health struggles may have played in his behavior.

A psychological evaluation, excerpted in court filings, described Muhammad as having post-traumatic stress disorder as well as bipolar disorder. His defense attorney wrote that Muhammad had stopped taking his medication during the period that he was in Portland, which exacerbated a manic state.

“He explained that when he enters this state, he feels ‘untouchable’: ‘I don’t think anyone can take me. I can’t die,’” prosecutors wrote, pulling from the evaluation. It said when he was manic, he heard “the voices of two or three men inside his head” giving him instructions.

“Once the mania fades,” prosecutors wrote, “he is anxious about the things he has done when he was manic.”

Now 25, Muhammad is slated to spend the next decade of his life in prison. His plea deal included 10 years in state and federal prison, but those sentences will run concurrently.

“He’s grateful that he’s able to resolve this case,” says Gerald M. Needham, Muhammad’s defense attorney.

For Multnomah County prosecutors—saddled with a reputation of being soft on protesters—the case is a victory: the longest sentence handed down stemming from the 2020 racial justice protests. Proud Boy Alan Swinney also received a 10-year sentence in December.

“There are few things in this world more terrifying than being burnt alive,” Vasquez said March 29. “These things tear at the fabric of our community.”

Chavez says the political implications of a dual state and federal conviction of a protester are not lost on him: “I think for the DA’s office, to me, I tend to think that this is solely because they are trying to buy back the confidences of the Portland Police Bureau.”