This story originally ran in the July 12, 2000, issue of Willamette Week.

Every so often the world forges a character who is larger than life yet cannot negotiate reality.

Jon Beckel was one of those. To the power of 10.

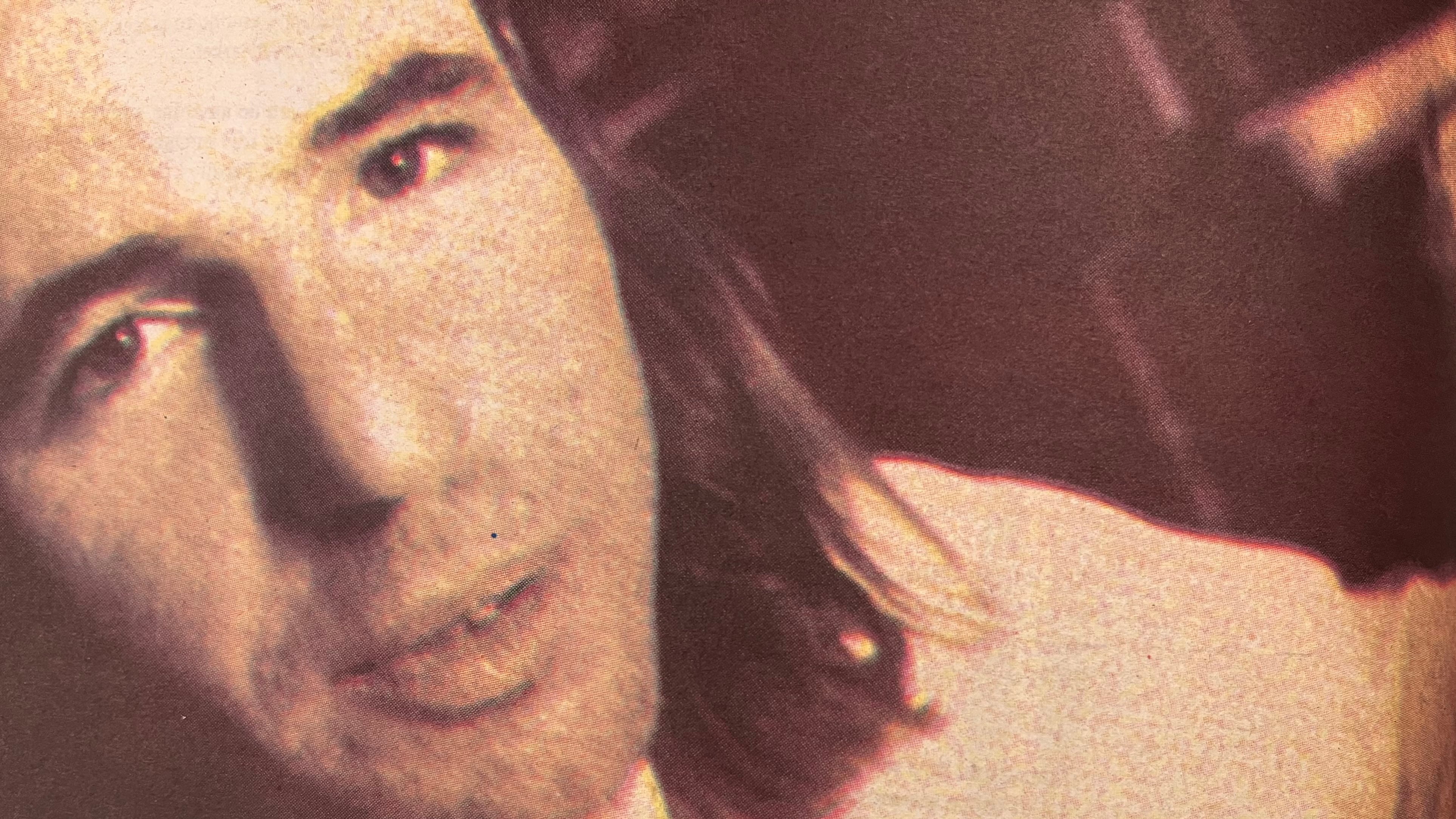

Sad-eyed and long-haired, the 39-year-old co-owner of Le Bistro Montage spent much of the last decade as the clown prince of Portland’s hipsters. It’s a role that required a blue-collar outlook, the uncanny ability to hit the right cultural high notes, an antic disposition and a bucketful of obnoxiousness.

Two weeks ago, reality caught up with Jon Beckel.

In the early hours of July 1, after watching his girlfriend’s band at Berbati’s, Beckel gashed his forehead somewhere in downtown Portland. Arrested later on outstanding misdemeanor warrants, Beckel was taken to the Justice Center, where he was forcibly restrained. At some point, he suffered a fatal brain injury.

No one knows precisely what happened. Did he fall and bump his forehead? If so, was it before he was in custody, or after? Was he injured by a corrections deputy?

Either way, Beckel’s brain stem was destroyed. On July 6, he was removed from mechanical ventilation and died at Oregon Health & Sciences University Hospital. His death was attributed to “head injuries with a left subdural hematoma,” according to Larry Lewman, a deputy state medical examiner.

Multnomah County Sheriff Dan Noelle is looking for answers to the riddle of Beckel’s death. Last Wednesday, his office turned its investigation over to the East County Major Crimes Task Force—an acknowledgement of just how complex the last day of Beckel’s life was, as well as an admission that the sheriff needs a political fig leaf. The task force only comes out to investigate murders, rapes and kidnappings. Its detectives will most likely take at least two weeks to piece together the mystery of Beckel’s death.

Alive, Jon Beckel would have been a full-employment project.

Now, it is for his friends and acquaintances to wonder what happened to Beckel on July 1— and debate who he was at core.

Although Beckel’s death is deeply unsettling, few people who knew him are surprised that his life led to such a moment. The 5- foot-11, 180-pound man lived large, played large, irritated even his closest friends and was infamous around Portland for picking fights that he regularly lost. He could be a saint or an asshole.

“Like rain in Oregon, you just had to wait five minutes,” says Terry Nelson, a friend of 19 years. “That’s the enigma of Jon Beckel.”

He was an accident, not just waiting to happen but often seemingly wanting to happen.

“Jon led with his chin everywhere he went,” says Nelson. “He was an amazing performance artist in how he lived his life. But you get those intense highs and lows with people who run emotionally on four barrels with a rich setting.”

On many Portlanders’ scorecards, Jon Beckel was brilliant, but his smarts were not college-bought.

After graduating from Madison High School in Northeast Portland, he left his native turf for Santa Barbara, Calif., where he worked in a Jack-in-the-Box and art galleries, eating Mexican bread and salsa when cash was low. It was here that he and Nelson met. They were later banned from the oceanfront pier for public drunkenness and wearing trench coats in 100 degree weather.

Trapped with no money in that most conservative of California cities, Beckel, with Nelson in tow, drifted north along Interstate 5 to Portland, a city that suddenly went from being a place where he’d been an awkward, mouthy teenager to one that was his playground.

It was 1985.

Nelson says his friend was fueled by visions of living out the minimum-wage fate parceled out to most men who passed on college in the 1980s.

“One of the things Jon feared was that life had dealt him a hand of cards that required him to work at Fred Meyer’s, leaving him under the fluorescent lights, saying, Thank you, have a nice day,’” says Nelson. “He’d do anything to avoid that.”

He and Nelson opened Time for Fun, a vintage watch shop on Southeast Belmont Street. Vintage watches were a hot item in those days, the harbinger of the 1990s retro clothing craze. After later moving the shop to Southwest Ankeny Street, Beckel persuaded Nelson to turn half of the space into a 24-hour espresso bar, the first in downtown Portland. Renamed Cafe Omega, it was a hit with hipsters, low-lifes and police officers alike. But owning a single watch-shop-cum-coffeehouse wasn’t the fast track to riches.

Still, by 1990 Beckel had scraped together enough money for a two-story, gabled house at the corner of Southeast Yamhill Street and 33rd Avenue in Sunnyside. The roof had a yawning hole. Neighbors’ first memory of Beckel

is of their new neighbor, drunk and perched on the steeply pitched roof, arcing empty beer bottles onto Yamhill Street to see what kind of pattern the glass made.

But after three years of 12-hour shifts, Beckel and Nelson had little to show for their efforts besides exhaustion. This was not living.

Sensing he was on the verge of being wedged into the quotidian, Beckel turned Cafe Omega over to Nelson in 1991. For a time, he cooked at Acapulco Gold’s.

And then came Beckel’s master stroke. Together with Daris Ray, a chef from Louisiana, he opened Le Bistro Montage on Halloween 1992. Located on Southeast Belmont Street, it was a restaurant unlike anything Portland had ever seen.

Sure, there was white linen on the tables, and Beckel and his staff wore boiled jackets crested with a monogrammed M, but these were flourishes of restaurant snootiness operating as wry social commentary.

Holding 44 people, Montage played into that studied blue-collar style that had roared through a bored generation of young adults like a Galaxie 500. Wine was served in tumblers, the lone beer was Rainier and Ray’s pasta and meat dishes revolved around a single roux. Montage’s culinary drawing card was “mac and cheese” for $1.50.

It wasn’t the food that compelled people to line up in the rain and drive the neighbors crazy with their late-night chatter while waiting for a table. Rather, it was Montage’s peculiar ambience that made the off-beat bistro so addictive—and that was almost solely Beckel’s handiwork.

“It fills a space you didn’t even know you had, and life without it is unimaginable,” WW wrote in naming Montage Restaurant of the Year for 1993.

The restaurant spoke to Portland’s burgeoning indie culture—and its heroin-chic afterbirth. It was a subculture of post-punk rockers, filmmakers, theater artists and their allies that defined what was cool in every major American city from 1990 to 1996, when all that was indie—goatees, piercings, lingerie as casual wear—had been so thoroughly co-opted by the mainstream that tattoo shops sprang up in suburban shopping malls.

It was a late-night salon for slackers, run by an impresario of the highest order, one who was typically as drunk as a Las Vegas showman.

Beckel’s schtick was refining low humor into living art. He was an obsessed fan of Phil Silvers and Bob Hope, both masters of comedic timing. Although he’d often sit down and jabber with customers in the most genuine manner, his most consistent approach at Montage—and in the Portland bars he frequented—was to walk right up to people and talk bowel movements and masturbation as if he were talking politics and stocks.

“He wasn’t from the here-and-now,” says Nelson, now the owner of Tug Boat Brewing Company. “He always tried to take a loony situation and make it loonier. That was his schtick.”

The schtick and the restaurant were such a smashing success that in the summer of 1994, Beckel and Ray moved Montage to its current site underneath the Morrison Bridge. The new place held more than 100 people and was regularly jammed with uncool city dwellers and suburbanites who’d come to gape at the hipsters. Beckel, of course, was still the featured act.

“There’s a lot of worshiping of people who refuse to conform,” says Anne Hughes, owner of the Anne Hughes Kitchen Table Cafe and the coffee shop inside Powell’s City of Books. “A lot of young people are that way these days. They want fun when they are eating, working and sleeping—and he provided that.”

The trouble with his act was he couldn’t turn it off. At times, it would devolve into a drunken Beckel mouthing off to the wrong guy at a downtown bar or club and winding up with his face bloodied. So poor was Beckel’s choice of opponents that he once had a cigarette stubbed out on his face.

But these were Montage’s and Beckel’s salad days. He met a sculptor named Rachel, and the two were married that October. And he was making so much money from the restaurant that he’d turned his junker house into a comfortable home.

His universe seemed to be in order.

Initially, Rachel Beckel gave the wildman entertainer’s life some much-needed structure. Still, Montage employees and Beckel’s friends considered the match odd. She was the quiet, introspective artist, while he was oftentimes more like a performing animal. Rachel’s work was hardened in a kiln; Jon’s work was ephemera stacked on top of ephemera.

But even as Montage prospered in the mid-1990s, the restaurant, and Beckel himself, took an ominous turn.

Montage’s core base of indie-hipsters had deserted the restaurant. They found the place a charade, what with all those urban tourists and a decline in service—running out of bread or not having enough leaf lettuce on hand.

Beckel’s drinking increased. In late mornings, Beckel would walk in to the bar at Produce Row, bolt two pints of Henry’s Private Reserve and head back to Montage with his first slug of medicine under his belt. And that was before he cracked the seal on a whiskey bottle. Daris Ray and the restaurant’s employees ran the place while Beckel roamed downtown’s bars and clubs.

Meanwhile, Beckel and Rachel fought. She’d lock him out of the house on occasion. In 1996, Rachel moved out, leaving him behind with two cats and “a lot of demons to sort out,” as a friend puts it.

In 1997, Beckel moved to San Francisco. Plans were to open a Montage, in North Beach, but the deal somehow fell apart.

By now he’d been banned from Montage’s business. He told former neighbors that he was moving to Fog City to devote himself to screenwriting.

Renting a studio in Chinatown, he tried to work through his mid-life crisis. It was not a pretty sight.

Beckel was scrambling to survive, going so far as to work at a diner. He owed the Internal Revenue Service tens of thousands in back taxes and paid Rachel, now his ex-wife, $2,000 a month in support.

But he continued returning to Portland every few months, unable to cut the umbilical cord, and stayed for weeks at a time.

During one of those trips in 1997, he was arrested in Milwaukie on a misdemeanor drunk-driving charge; he never appeared at court hearings for a diversion program. The next summer, he was stopped for drunk driving in Gearhart. After working out a plea bargain in February 1999, he didn’t even show up to serve his four days in jail, much less comply with any of the terms of his probation.

Two warrants were issued for his arrest—flags in the criminal justice system that ultimately figured large in the last days of his life.

At one point in 1998, he was in Portland long enough to be involved with Bella Rattan, a woman who, according to friends of Beckel, had it together even less than he did at the time and who wildly exaggerated their relationship. In November, a restraining order was issued against Beckel after Rattan alleged that he’d twice smashed her into a wall while drinking Wild Turkey. Rattan obtained a second restraining order against Beckel on April 25, 2000, claiming that he had sent her intimidating mail from Nicaragua.

Beckel, however, had recently moved back to Portland to live with Juliette Jones. She was a friend of eight years, and they’d remained in contact during his years of yo-yoing between Portland and San Francisco; for her, Beckel cut his hair above the ears.

He even told old friends and acquaintances he bumped into that he was madly in love, although he wouldn’t tell them with whom. In recent weeks, he had been shopping for a wedding ring.

The evening of June 29, he was drinking with members of the old Montage crew at the Aalto Lounge on Southeast Belmont Street, less than two blocks from his former home.

“It was like we’d seen each other yesterday,” says Anne Hughes, who ran into Beckel in the wine bar that warm evening. “He seemed fine, but he’d definitely been drinking.”

June 30 was a warm evening with a cool breeze out of the west. Beckel was nervous. For three months, he and Jones had kept their relationship shielded from onlookers; now, they were going public. He was going out that night to watch his fiancee play bass in the band Natron at Berbati’s Pan on Southwest 3rd Avenue.

As part of an anti-Portland Blues Festival show, Natron himself was taking a page out of blues voodoo: He would emerge from a glass-lidded coffin after midnight.

Sometime after 1 am, the show ended. Beckel talked to his fiancee for a few minutes as she broke down her bass rig.

Wearing a black jacket and a white shirt, he left Berbati’s between 1:15 and 1:30 am, heading for Jones’ apartment on Southwest Vista Place, heading also into a mystery as big as himself.

To date, no one knows what happened next. But there are a few facts that make it possible to entertain tentative theories as to how Beckel died from a subdural hematoma, i.e. bleeding into the brain, commonly the result of blunt trauma.

At 1:47 am, responding to a 911 call made by an onlooker, Portland police found Beckel bleeding from a cut above his eye at Southwest 18th Avenue and Morrison Street. He was too drunk to stand, according to law-enforcement sources, and was transported by ambulance to Legacy-Good Samaritan Hospital, where he arrived at 2:10 am.

Meanwhile, police had run Beckel’s name through the state’s LEDS database. Two warrants for Beckel’s arrest came up; police asked hospital personnel to contact them when Beckel was ready for discharge.

At 2:59 am, hospital personnel contacted police. Emergency medicine experts contacted by WW said the hospital could not have thought Beckel’s injury presented any threat; otherwise doctors would have insisted upon an X-ray as a minimal precaution, pushing Beckel’s hospital stay well beyond its 49 minutes.

Instead, Beckel was discharged at 3:20 am. He went to a pay phone and called his fiancee.

“He knew something was going to go down because of his warrants,” Jones says. “He sounded worried and said, ‘I’ll call you back.’”

Officer A. Nakamura arrested Beckel at the hospital at 3:31 am. Twenty-five minutes later, he drove his white squad car down the long spiral ramp to the Justice Center’s so-called “sally port.” Nakamura handed Beckel over to corrections deputies without incident. According to the officer’s custody report, Beckel’s eyes were bloodshot, his speech was slurred and his breath smelled of alcohol.

It was 3:59 am.

The Justice Center’s booking facility is lit by fluorescent lights, the floor is tan-and-orange linoleum, the cinder block walls are painted cream. Detainees are searched twice by a deputy dressed in green; shoe laces and belts are removed. Fingerprints are taken, followed by mug shots. Next stop is the nurse’s station, where detainees are asked a series of medical questions.

It is a noisy and stressful environment for all concerned, especially early on Saturday and Sunday mornings.

The nurse’s station is 200 feet away from the sally port. Somewhere between those two points, Jon Beckel resisted the process. An unidentified male deputy threw Beckel to the floor with a “hair takedown,” a procedure that is to be employed when a detainee’s actions are “ominous,” according to Sheriff’s Department policy. Because of the takedown, Beckel’s head hit the floor.

He was then placed in a 40-square-foot isolation cell 10 feet away from the nurse’s station. The cell, which has no mattress but offers a bedstead of solid wood, is where rowdy drunks and potentially violent detainees are held until they shape up.

With his dinged-up forehead and dirtied clothes, Jon Beckel must have looked like just another uncooperative drunk who needed to gather himself together.

Although the East County Major Crimes Task Force is looking into each moment that Beckel was in the hands of law enforcement, it is to the minutes and hours in the cell that its detectives should pay the strictest attention. Lying in that cell with his injuries partially masked by his inebriation, Beckel slipped into permanent unconsciousness.

Saints and sinners bleed the same. For as many as 10 hours on July 1, Jon Beckel—both sinner and saint—bled into his brain, and it seems that no one caught it until 2:30 pm when the Justice Center contacted 911.

Up at OHSU, on the evening of July 6, five people were figuring out how to bid farewell to someone who’d left as deep an imprint as Beckel had.

His father, Robert, had just signed the release forms allowing doctors to remove his only son from life support. Along with his second wife, the elder Beckel quickly departed.

That left Arthur Chessman, an old friend, and Rachel and Juliette. After Beckel was removed from mechanical ventilation and his heart stopped at 10:15 pm, they placed crimson and white rose petals around his body.

“I keep getting phone calls and people say how much they loved him,” Terry Nelson said the following day. “Then they say, ‘The world has one less wise-ass now.’

“Beckel had such a goddamned great run. But it’s so like him not to go out quietly—he’s got to leave with a bang and a question mark.”

—Kelly Clarke, Jenny Egan and Alley Hector contributed research to this article.

On July 19, 2000, WW published the following update.

Putting the Pieces Together

Is the mystery of Jon Beckel’s death solved?

According to Larry Lewman, a deputy state medical examiner, it is. Lewman told Beckel’s family Tuesday that the 39-year-old suffered a brain injury on July 1 as a result of falling to the street in downtown Portland.

Lewman’s conclusion counters the theory that Beckel’s injury may have stemmed from excessive use of force by corrections deputies at the Justice Center, where Beckel was taken July 1 on outstanding drunk-driving warrants. Beckel, the co-founder of Le Bistro Montage, died July 6 after being removed from life support (“What Happened to Jon Beckel?” WW, July 12, 2000).

“The most significant impact to his head was his fall,” Lewman told WW Tuesday. Lewman estimated that at the time of his fall, Beckel’s blood alcohol level was .30 percent—almost four times the legal limit of .08 percent.

Lewman said records show that Beckel complained of a headache while in custody the morning of July 1, but did not collapse until that afternoon when he was being moved from an isolation cell into the general jail population. WW’s request for records regarding Beckel’s treatment and monitoring while in jail have been denied by county corrections officials.

Despite Lewman’s findings, The Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office still plans to refer the case to a grand jury next-month, WW has learned. It is common for District Attorney Michael Schrunk to invoke grand juries in fatal situations involving law-enforcement officers.

Beckel’s family has consulted with attorney Chuck Paulson but has not decided whether to bring any legal actions.

The East County Major Crimes Task Force expects to complete its investigation of Beckel’s death within one week. —Philip Dawdy