Steve Pedery and U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) see Mount Hood a little differently.

Pedery, the conservation director of Oregon Wild, had mixed feelings about a December map his team prepared, which detailed the proposed expansion of conservation protections in the 1.1 million-acre Mount Hood National Forest.

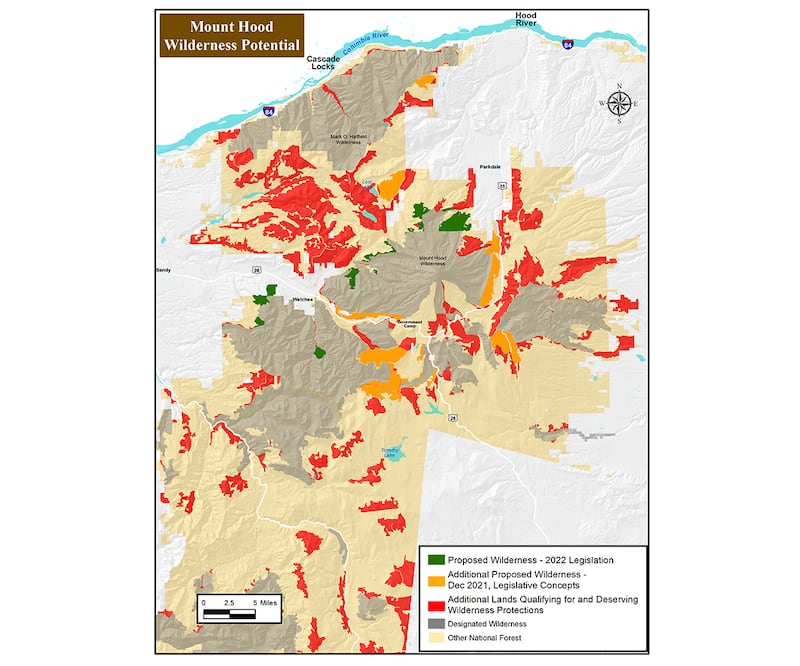

The map showed the addition of about 30,000 acres designated “wilderness.” That means the land is off-limits to logging, and it prohibits the use of any mechanized equipment, from road graders to chainsaws to recreational vehicles—including mountain bikes. Pedery and his colleagues had hoped for more.

On May 11, the Blumenauer-penned Mt. Hood and Columbia River Gorge Recreation Enhancement and Conservation Act gets its first hearing. But instead of adding 30,000 acres of new wilderness protection, it would add just 7,500 acres.

That 75% reduction was enough for Oregon Wild, which has 3,500 dues-paying members and a 25,000-name email list, to withdraw support and activate its constituents to contact Blumenauer.

“This bill is a fiasco,” Pedery says. “It feels like the kid who showed up for class not having read the book report his parents wrote for him and submitting an entirely different report he wrote on the back of an envelope.”

Wilderness designation is the highest level of protection federal land can have. A 2009 bill protects 127,000 acres in the Mount Hood National Forest with that label. But Oregon contains about half the wilderness that Idaho and Washington have set aside on a percentage basis, and just a third of what California has preserved.

Oregon Wild had hoped a new Mount Hood bill would help change that. The group worked for much of the past decade on a bill it hoped would protect a chunk of the remaining 178,000 acres in the forest it believes qualifies as wilderness.

That didn’t happen. In fact, the proposed wilderness area shrank and excluded two of Oregon Wild’s highest priorities: Tamanawas Falls and Boulder Lake.

That reduction highlights a fundamental conflict over Mount Hood. The urban and suburban hikers Oregon Wild represents make up a substantial segment of voters in Blumenauer’s district.

But Blumenauer’s newly redrawn district shifted to the east, picking up Hood River County and the east side of Mount Hood. Constituents there have different interests from his neighbors in Northeast Portland. (His spokeswoman, Hillary Barbour, says the boundary change didn’t alter Blumenauer’s priorities.)

Pedery says the draft bill fails to recognize the extraordinary increase in recreational use of Mount Hood and makes it easier rather than harder for the U.S. Forest Service to sell more timber.

Blumenauer says that’s a misreading of the bill. He says Pedery’s criticism also fails to consider the broad range of interests that have a stake in Mount Hood.

“My record on wilderness areas is pretty strong,” Blumenauer says, “but the bill has to be supportable and something that can be passed.”

Blumenauer says that far from being a capitulation, his bill designates 350,000 more acres as national recreational area and represents a first-in-the-nation effort to allow tribal co-management. The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs’ reservation lies east of Mount Hood.

Tribal council chairman Jonathan Smith said the bill “ensures that tribal interests and traditional ecological knowledge are integrated into forest management for the benefit of all Oregonians.”

Blumenauer adds that groups whose visions of Mount Hood diverge from Oregon Wild’s, including mountain bikers and agricultural interests, also helped shape the bill. (Nate Kuder, president of the Oregon Mountain Biking Coalition, calls the bill a “transformational model of public land conservation.”)

Blumenauer disputes any assertion he wants to make it easier for the Forest Service to sell timberº.

“The timber industry is not my most enthusiastic support group,” Blumenauer says. “We’ve been dealing with this [wilderness] issue around Mount Hood for years. The easy stuff is gone. What we’ve got left with Mount Hood is where there aren’t many obvious candidates for additional wilderness.”

Blumenauer says in recent months that input from Warm Springs and others on the east side of Mount Hood helped shape the final bill—and reduced the acreage that could become wilderness.

One of the people pleased with the result is longtime Hood River County Commissioner Les Perkins, who in his day job manages Farmers Irrigation District.

Perkins says the five Hood River irrigation districts have water rights on Mount Hood that preceded the creation of the Forest Service. Floods, fires and other events in the watersheds that supply those districts frequently require mechanical fixes—but they are forbidden in wilderness areas.

“For the past couple of months, Earl Blumenauer and his staff have been very engaged,” Perkins says. “We showed them our [geographic information system] maps of where our infrastructure is located, and they moved their boundaries.”

All constituents recognize the need for more and better-maintained hiking and riding trails, Perkins says, and he thinks Blumenauer’s bill, which proposes funding for such expansions as well as wildfire assessments, can deliver that.

Pedery is unconvinced. He says the additional national recreation area designation is “greenwashing.” Not only does the bill put the Pacific Crest Trail and other iconic terrain at risk, but it fails to prioritize recreation over timber sales. It proposes expanding justifications for cutting to include improving watersheds, enhancing scenic character, and increasing carbon sequestration. Pedery says it’s impossible to do any of those things by cutting down trees.

“We normally have a good relationship with Blumenauer, but this doesn’t feel like a Blumenauer bill,” Pedery says. “The people we represent in his constituency want more wilderness.”