Between 1960 and 1980, the city of Portland and the state bought 1,000 houses in the Albina District—and bulldozed them all.

Black Portlanders owned many of those homes, but officials wanted to make way for Interstate 5, Memorial Coliseum, Legacy Emanuel Hospital and Portland Public Schools’ district headquarters. So, using the power of eminent domain, they flattened dozens of blocks.

The effort dislocated families from their homes, the greatest source of wealth for most of them, and eliminated Black-owned businesses and other gathering places in the neighborhood. (The city and state bought out homeowners and compensated renters, but critics say those payments were insufficient.)

It was a historic injustice for which the city is now trying partly to atone.

Since 2014, it has been spending big money—$91 million to date—to stem the tide of gentrification and displacement that bleached Portland’s historically Black neighborhood white.

The goal? To keep families in Albina from having to move; to build new, subsidized apartments that give preference to families who were displaced; and to help other displaced families buy homes and return to their old neighborhood.

The results of what the city calls the North/Northeast Neighborhood Housing Strategy are mixed. In 2018, Mayor Ted Wheeler called it an “abject failure.” Today, a national housing discrimination expert says Portland’s strategy is a “pernicious” attempt at resegregation.

At the same time, for 94 families who’ve been able to buy homes through the program, it’s life changing. And 400 other families have been able to move back into new, city-subsidized apartments in Albina.

For this reason, supporters argue that the North/Northeast Neighborhood Housing Strategy is a national model.

Bishop Steven Holt, who lived in an Albina home that was later leveled, now chairs the oversight committee that directs city spending on the program. Last month, Holt led a presentation before the Portland City Council on the strategy’s accomplishments after eight years.

“This story,” Holt tells WW, “is miraculous. We don’t tell it well enough or often enough.”

Others say that despite the undeniable benefits of the city allocating more than $100 million to preserve homes and bring families back to Albina (the total budget is $138 million, of which $47 million remains unspent), the policy allows city leaders to assuage white guilt while benefiting a relative few.

To such critics, the strategy is a noble gesture but ultimately a fig leaf.

Darrell Millner, former chairman and professor emeritus of Black studies at Portland State University, says the city is not tackling the larger issues that prevent a wide range of low-income families in Portland—not just those displaced from Albina—from being able to afford homes and build wealth.

“It’s kind of a typical Portland reaction to an injustice,” Millner says. “It’s a feel-good story that doesn’t move the needle very much.”

During the past six months, WW has reviewed stacks of documents and spoken to dozens of people with connections to Albina or the city’s policy, which some call a “right to return.” Nobody ever expected the policy to make up for decades of injustice, but Portland—and Albina—are less affordable now and arguably less equitable than ever.

“We have about 300 people working for us, most of them women, Black or Latina,” says Ron Herndon, executive director of Albina Head Start. “Many of them have been forced to move to Vancouver or east county because they just can’t afford to live here.”

Portland has a lot of history to overcome.

That history included the legal prohibition of Black people from living or owning land in the state in the 1800s. It included segregation, first in Vanport in the 1940s—which ended when it flooded in 1948, causing the death of 15 people and the destruction of the state’s second-largest city. After the flood, most of the city’s Black residents lived in the Albina District, trapped there by racist lending policies and victimized by predatory landlords.

De facto segregation concentrated the city’s Black population in a small geographic area. Churches, Black-owned businesses, restaurants and stores lined North Williams and Vancouver avenues.

“The Black community was an artificial construct,” Millner says, “but it was also a haven in a very hostile environment.”

In 2013, the Portland African American Leadership Forum (now Imagine Black) demanded an accounting from the Portland Development Commission (now Prosper Portland) for the urban renewal efforts that gutted the neighborhood. Those projects first destroyed homes and businesses but later generated tens of millions of dollars in new tax revenue.

“We wanted to know how much of the urban renewal money was spent for the benefit of African Americans,” says Cyreena Boston Ashby, who was then PAALF’s executive director. “How much on African American businesses, and how many people who got money employed Black people?”

At about the same time, PDC sold a piece of property in the heart of Albina to a white California developer who planned to build a Trader Joe’s there. It was a public relations nightmare for the city, and then-Mayor Charlie Hales and Housing Commissioner Dan Saltzman needed something to quiet their critics.

In March 2014, Hales announced his North/Northeast Housing Strategy.

Hales offered home repair loans and grants to families living in Albina; the construction of new, affordable housing in the neighborhood; and forgivable loans to help returning families buy homes. The city would also try to buy land for future development.

The program gave priority to low-income families who could prove historical ties to Albina. The highest priority went to families whose homes the city had seized by invoking eminent domain.

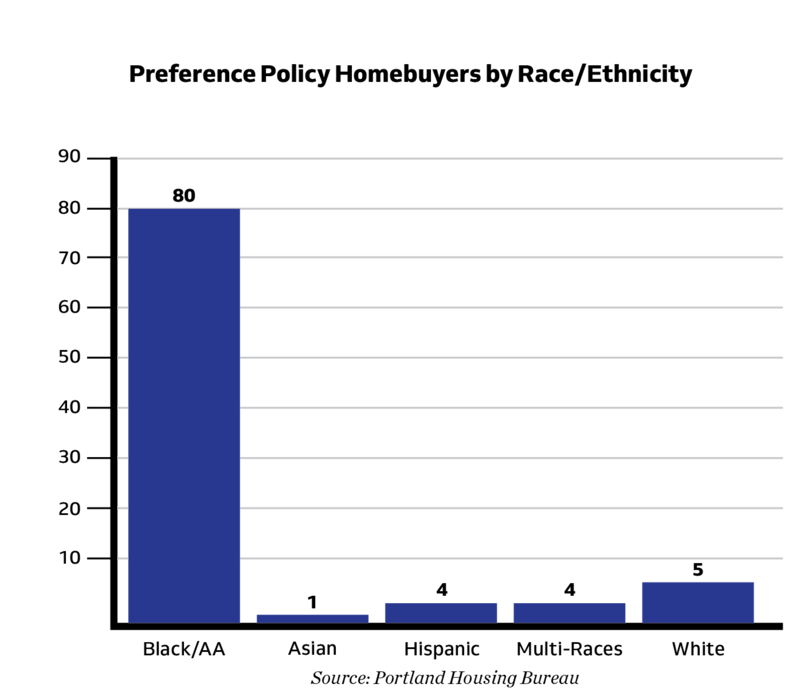

The preference policy had to be artful because federal fair housing laws prohibit preference or discrimination based on race. (Race is not an explicit factor in Portland’s policy, although records show the vast majority of those who have returned are Black.)

Initially, the required documentation proved difficult. “I always felt like what keeps a lot of low-income people and people of color down is the process itself,” says Tony Hopson, executive director of the social services nonprofit Self Enhancement Inc. and part of the PAALF group that prompted the city’s policy.

There were hiccups: WW reported in 2019 that one new building filled very slowly because of a conflict among the developer, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, and the Portland Housing Bureau over whether PCRI could use its own list of applicants or the city’s list.

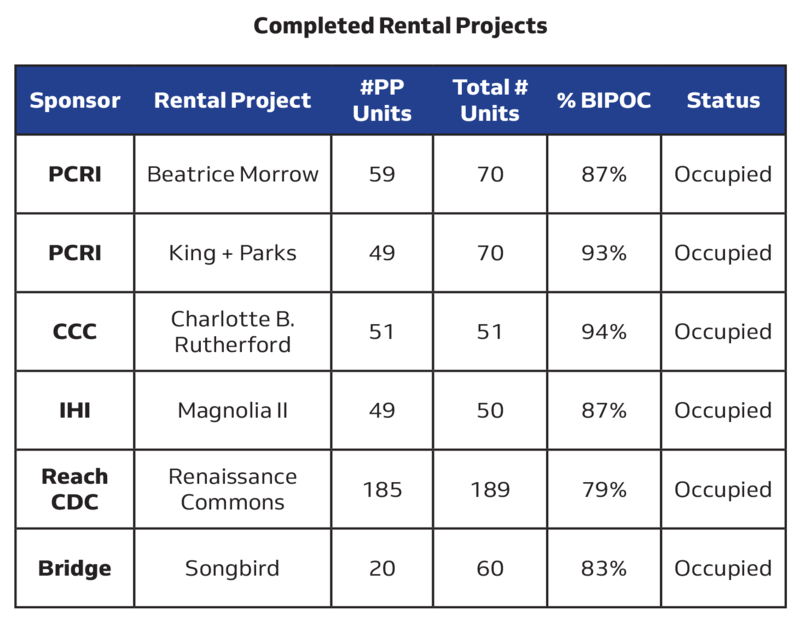

But there’s been progress. Over the past four years, six new apartment buildings that include 501 units were built. Approximately 400 of those units are set aside for tenants using the preference policy.

One of them is King + Parks, a brick-clad, 70-unit townhouse and apartment complex. It’s a project developed by the Black-run nonprofit PCRI and built by a Black-owned construction firm, Colas Construction, to provide affordable apartments and condominiums mostly for Black families with historical ties to Albina.

Like other public housing programs, demand far outstrips supply: There have been 3,782 applications for about 400 rental slots. And critics say that although providing affordable apartments for displaced families is better than doing nothing, it doesn’t help them build wealth, which economists say is the strongest protection against displacement.

That’s why the city’s effort to help exiled families buy homes in Albina is arguably more important than the rental strategy. It’s also demonstrably less successful.

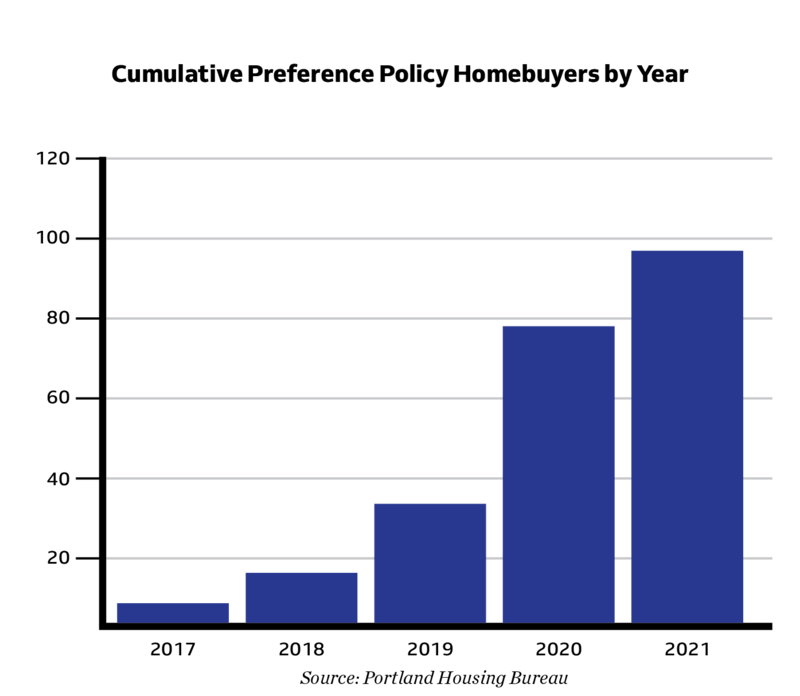

In April 2018, when the N/NE oversight committee presented its third annual report to the City Council, Mayor Wheeler could not disguise his disappointment that the policy had yielded just five new homeowners.

He called it an “abject failure.”

Housing Bureau director Shannon Callahan had just stepped into her role when Wheeler provided his assessment.

“I would not have chosen to use those two words,” Callahan says, “but he wasn’t wrong that we needed to make changes.”

The city has since streamlined the down-payment loan process, connecting homebuyers who may be able to qualify for a mortgage with the nonprofit Portland Housing Center, which helps them improve their credit rating and financial profile. Still, it often takes two years for buyers to prepare. (The city provides a $100,000 down-payment loan, which is 50% forgivable after 15 years and fully forgiven after 30 years.)

The number of new homeowners created through the strategy is now up to 94, although that number includes at least 18 homes outside Albina. And the total is just a fraction of the 1,622 applicants to the homeownership program.

“We’re seeing some forward momentum,” Wheeler now says, “but we have a lot more work to do and we need to stay at it.”

For some, the city’s strategy is too little, too late.

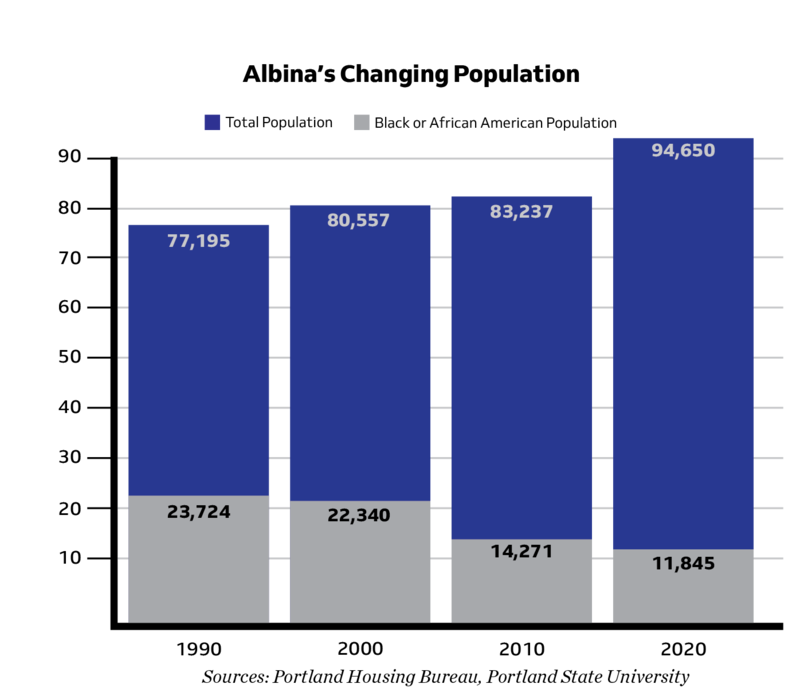

SEI’s Hopson, now 68, grew up in Albina when the Black population was more than two and a half times the percentage it is today (see chart below). His organization’s headquarters is in Unthank Park in the Albina neighborhood, and it’s also suffered from displacement.

“Most folks that work for SEI can’t afford to live in the neighborhood,” Hopson says. “I don’t see that changing. There’s no predominantly Black neighborhood in Portland anymore, and you can’t turn the clock back.”

Like Hopson, Roslyn Hill, a Black architect who bought a commercial property on North Alberta Street in 1993, says it’s impossible to re-create the Black Portland community of her youth.

“It’s too late to do it the way they are trying to do it,” Hill says. “The neighborhood doesn’t have the culture anymore. A lot of the Black churches aren’t there anymore. And a lot of the stores and the businesses, they are not friendly.”

The look of the neighborhood just isn’t the same. “I’m on Alberta Street all the time,” Hill adds. “Usually, I don’t see anybody who looks like me.”

Those who have come back have expressed thanks and some ambivalence. In a study of residents who have returned to Albina using the preference policy, Amie Thurber, a PSU assistant professor of social work, found that returnees reported joy and a strong level of civic engagement. They also described a sense of alienation from their move back to a neighborhood that had grown whiter, more affluent and less welcoming. Some said they experienced “persistent racism.”

Ta’ Neshia Renae, 39, a disabled veteran and mother of two teenagers, bought a home last May with help from the city. After an unstable childhood spent bouncing from temporary home to temporary home, mostly in Albina, she joined the military. When she came back to Portland, she was priced out of her old neighborhood until she qualified for a forgivable city loan.

Renae felt profoundly grateful when she got the keys to her place in Northeast. “I never thought I’d be able to do it,” she says. “I felt a real sense of accomplishment. Now I have something I can leave to my kids.”

Renae also feels somewhat conflicted. If the city only aimed to right wrongs and give her the opportunity to be a homeowner, she says she could have gotten a lot more for her money in Gresham or Parkrose. And, she adds, the Northeast Portland of her youth is gone.

“It doesn’t feel like home anymore,” she says. “I feel like a stranger. It’s pretentious, it’s wealthy, and it’s expensive—you’ve got a make $100,000 a year to live in this neighborhood.”

Some wish the city focused more directly on a root cause of displacement—the lack of wealth in the Black community.

In 2020, the Brookings Institution found that the median wealth of white households in America was about eight times that of Black households. Much of the gap is attributable to white families being more likely to own and pass along the wealth created by owning a home to their heirs.

One Portland group, the Emanuel Displaced Persons Association 2, wants direct compensation for families whose homes were taken for the construction of the Legacy hospital campus.

The Housing Bureau’s Callahan says it would indeed be possible to identify people whose families’ homes were seized and destroyed. Those transactions were well documented.

“We’ve got a list,” she says.

But the city has rejected the option of directly compensating such families.

Professor Gerard Mildner, director of the PSU Center for Real Estate, says the city’s approach allocates scarce resources inefficiently.

“Your chances of getting the $100,000 down payment are few and far between,” Mildner says. “There could be two families with equal circumstances, and one gets it and one doesn’t. That seems inequitable to me.”

Craig Gurian, executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center in New York, says housing preference policies like those in New York and Portland are a form of resegregation. (His organization is suing New York over its preference policy, which is similar to Portland’s.)

Gurian, who describes his politics as “way off to the left,” says giving preference to Black families to return to their old neighborhood is a misguided attempt to replicate the concentration of Black families caused by redlining and prohibitions on where Black people could live. Preference policies, he says, are based on premises that are either “false or pernicious.”

“The idea that somehow Black neighborhoods formed naturally or organically as opposed to what happened everywhere in the country, where there were many places that Black people could not live, is just wrong,” he says.

Gurian says preference policies divert focus and resources from true equity: “The people who need housing fight over scraps, and the people who have it just sit back and laugh because the basic structures aren’t being dealt with.”

PSU’s Millner agrees with Gurian that the city’s policy fails to address the high housing costs that afflict all low-income Portlanders, not just those exiled from Albina.

Millner moved to Oregon to get his Ph.D. in 1970. Since then, he’s become an expert on the history of Black Oregonians going all the way back to 1788.

He says he’s glad that 94 families, most of them Black, have become homeowners through the city’s strategy and others have found apartments. “That’s great,” he says, “but it’s a drop in the bucket.”

Lawmakers have ended single family zoning and made other changes to promote housing production. Millner wishes city leaders would also pressure the state to also rethink the region’s urban growth boundary, the limitation on development Oregon put in place in 1980.

Although many Oregonians say the UGB is a leading example of the state’s progressive values and even its exceptionalism, Millner sees it differently. To him, the limitation on where people can build homes is a policy akin to redlining, benefiting those who own land inside the boundary while punishing those who do not.

“A lot of the rationale for the UGB was saving the farmland,” Millner says. “The lack of land has never been a real issue in Oregon. I think it’s more that progressives who live in cities want to be able to drive less than 30 minutes and see goats and chickens.”

Portland regularly ranks among the nation’s least affordable cities, meaning that residential real estate prices and rents are high relative to income. And since 2000, Portland home prices have risen faster than in all but five of the nation’s 40 largest metro areas, according to the Case-Shiller index. (In Albina, during the first five years of the preference policy, home prices rose 20% faster than the city average and ended 31% more expensive than the average Portland home.)

Supporters of the UGB say the policy is aimed at delivering dense, walkable city centers while preventing sprawl and preserving farmland.

They disagree with Millner’s premise and say other factors, such as zoning and permitting restrictions, are to blame for the region’s shortage of affordable homes and apartments. Nick Christensen, a spokesman for Metro, the agency that regulates the UGB regionally, notes that home prices in Salt Lake City are comparable to Portland’s, while prices in Austin and Sacramento are only slightly lower.

“None of these cities have urban growth boundaries,” Christensen says.

But Jerry Johnson, a Portland housing economist, says the density of urban development that Metro and others want comes at a high price: For it to pencil out, rents for high-rise apartments must be $4 a square foot. That’s twice the current market rate.

Rather than trying to roll back the clock in Albina, Millner says, policymakers should seek to help a larger number of low-income residents across Portland.

“The city is more interested in superficial solutions and never deals with the complexities of the underlying problem,” he says. “That’s affordability.”

Clarification: this story originally said the city bought 1,000 Albina homes. In fact, the Oregon Department of Transportation bought some of the homes.

This story was reported with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.