When Jeanne Atkins was Oregon secretary of state, she visited all 36 Oregon counties, checked out their elections operations, and met with county clerks.

She was impressed with all of them, with one exception: Clackamas County, where County Clerk Sherry Hall has held office despite almost 20 years of blunders and scandals, including misprinted and misplaced ballots and the felony conviction of an elections staffer.

“A lot of people had questions about Clackamas County,” Atkins says in a recent interview recalling her visits in 2015 and 2016. “I came away from there not quite as assured about things as I did from other counties.”

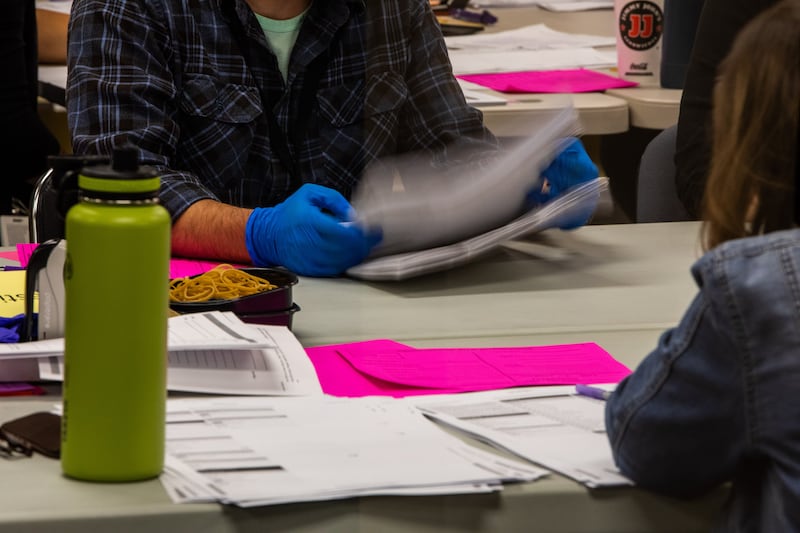

Atkins was right to be concerned. At this very moment, Hall is presiding over perhaps the biggest election snafu in Oregon history. While other counties are almost done with their vote counts, Clackamas has two rooms full of county employees trying to accomplish by hand over the course of days, or maybe weeks, what machines could have done in hours.

The problem started in early May with a blurry bar code on ballots printed for the county by a Bend firm called Moonlight BPO. It grew worse after Hall refused help from county commissioners and the state to hand-duplicate the ballots onto new ones that could be read by machines, costing valuable time and imperiling certification of the election, which the county must complete by June 13.

The outcome of several key races hangs in the balance, including the Democratic primary for Oregon’s 5th Congressional District, where incumbent Kurt Schrader clings to slim hopes for an eighth term against Jamie McLeod-Skinner, a progressive from Terrebone.

That result, among others, hinges on ballots under the oversight of Hall, a Trump supporter whose lackadaisical management has observers questioning whether the fiasco stems from incompetence or malice toward the institution of Oregon’s vote-by-mail elections.

“We never had anything this alarming happen under my tenure,” Atkins says. “It’s so contrary to everything I learned by sitting down with clerks and talking about their process.”

The question now is whether Clackamas County voters, who have stuck by Hall for five terms, through more than a dozen scandals and gaffes, will finally toss her out this November. (Hall is one of the county clerks in Oregon who are elected. The others are appointed.)

Because Hall’s race is nonpartisan, and because only two people are running, there was no primary. Her opponent in November is Catherine McMullen, a program specialist for Multnomah County Elections.

As an elected official, Hall is insulated from mechanisms that might be used to remove her from office. Many other county clerks are employees who can be fired. That said, evidence this week shows Hall may have lied about a matter brought to her attention by the McLeod-Skinner campaign.

Earlier this month, McLeod-Skinner alleged to Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan that Clackamas County Elections violated state law by allowing a representative of Schrader’s campaign into the office an hour before admitting an observer from McLeod-Skinner’s.

A log sheet provided by the elections office in response to a records request by WW shows a Schrader campaign representative signed in at 7:30 am Thursday, May 19. The office officially opened at 8:30 am, and a McLeod-Skinner observer signed in eight minutes later.

At a press conference the next day, Hall said she had no idea how someone could have gotten in before business hours on the 19th. It was possible that an employee badged in and someone followed, she said.

Then, on May 24, the county released video showing Hall walking out of the counting room and into the observation area with an elections worker identified by the county as Tiffany Clark at 7:36 am. Seconds later, Clark is seen on another camera letting a visitor into the building.

The incident raised the ire of Fagan, who was already exasperated by Hall’s performance.

“It’s absolutely outrageous to stand in front of the public and say one thing and then have a video showing something very different,” Fagan said at a press conference May 24. Fagan said state law prevents her from taking over a county election and that she was working with Hall to get the votes counted and certified.

“The county clerk is the only person who can conduct this election,” Fagan added.

All of which means the heat is on Hall, 70, like never before. But you’d never know it from her appearance at an emergency meeting of county commissioners last week and at a subsequent press conference. At both, the redheaded Hall seemed unfazed behind her distinctive rectangular eyeglasses, as if she were talking about a plugged toilet in the elections building, not a crisis that is shaking public confidence in elections at a time when they need no more shaking.

Steve Kindred, who worked for Hall as Clackamas County elections manager from 2010 to 2017, says that’s Hall’s weakness. Elections are complicated, Kindred says, “but when this stuff happens, Sherry doesn’t attack the problem and fix it. There’s a lack of energy. She didn’t really work a 40-hour week and wasn’t always around to answer questions.”

So far, Hall’s gaffes appear to stem more from her work ethic than her politics. In her campaign literature, Hall says: “I don’t accept or give endorsements because endorsements are political statements. Elections are process oriented, not politically oriented. As Clerk, I will continue to keep politics out of the office and protect your vote.”

But her Facebook page tells a different story. Among her liked pages are “Donald Trump Is My President,” “Judge Jeanine Pirro Has Fans,” and “The Daily Caller.”

Hall graduated from Milwaukie’s Rex Putnam High School and attended Eastern Oregon University. She was a legal secretary in the Clackamas County District Attorney’s Office when she first ran for clerk in 2002, listing her government experience as serving on a DUII panel and the Oregon Trail Pageant board.

The Clackamas County elections blunders began a year after Hall took office. In 2004, her office mailed ballots to some 300 voters in Sandy that excluded three questions about land annexation. Hall discovered the error 10 days before the election but failed to alert the public, according to The Oregonian.

In 2010, Hall included the race for Position 3 on the Clackamas County Board of Commissioners on the May ballot, even though it was not supposed to appear until November. The state Elections Division ordered all county ballots to be reprinted at a cost of $118,000. Voters’ Pamphlets also contained wrong information.

A year later, state elections director Steve Trout had to monitor the county’s process for verifying petition signatures after he concluded Hall’s office had accepted invalid signatures for a measure to require voter approval of county funding for light rail.

“She has a deserved reputation for incompetence,” says Peter Toll, volunteer chairman of the Clackamas County Democratic Party’s campaign committee, who’s lived in the county since 1989. “She’s been there too long and is totally unable to keep up.”

Hall’s biggest blunder may have come in 2012, when a Clackamas County elections worker named Deanna Swenson got caught filling in votes for Republican candidates on ballots in which voters had left choices blank. Swenson, who told The Oregonian her judgment had been clouded by medication for a sinus infection, was sentenced to 90 days in jail.

Beyond elections, county clerks also officiate at civil weddings. Hall did that regularly until 2014, when same-sex marriage became legal. Then she stopped.

Kindred, Hall’s former elections manager, says many of the errors over the years weren’t Hall’s fault, though they happened on her watch. The question of when a race should appear on the ballot, in May or November, is complicated, he says, and depends on whether an officeholder is appointed or elected.

In the Swenson case, Kindred thought the county deserved some credit for catching her early, getting her out of the counting room, and reporting her to law enforcement. “To me, that was a success,” Kindred says.

Some things, though, Kindred can’t forgive. He wrote an op-ed in the Clackamas Review about Hall’s halt to weddings. Then he filed a complaint against Hall with the state in 2014 after she asked him how he’d answer a series of questions about ballot tampering and working relationships with other county departments. He didn’t think much of it until he saw his answers in a story about Hall’s candidacy in The Oregonian. He thought he had inadvertently broken the law by working on a campaign during county business hours at a county office.

Kindred says Hall agreed to report the incident herself, after the election. She was found guilty and fined, Kindred says. From then on, Hall treated him differently.

“Those years were not really comfortable,” Kindred says. “I retired when I could.”

Toll of the Clackamas Democrats says Hall keeps winning reelection despite her poor performance for two reasons: The old guard in Clackamas County likes her, and the race for county clerk appears so far down the ballot that many voters don’t get to it.

“People don’t go to the bottom,” Toll says.