Rick Emerson was 14 when he happened upon a copy of Go Ask Alice on the return shelf of his Kennewick, Wash., school library.

Such an encounter was common in 1987—the book had sold 3 million copies since its 1971 publication—and also a little lucky: Three years later, the American Library Association would list Go Ask Alice among the most frequently banned books in the country.

The attraction and repulsion were both baked into the book’s premise: It purported to be the uncensored diary of an anonymous California teenage girl who was dosed with LSD, got hooked and died, leaving only her notebooks as a document of her dissolution.

Young Rick devoured it. Twice. “I read it and then went back to the beginning and read it again,” Emerson recalls now. “I was just sort of intrigued by the idea of who is this girl? How can nobody know?”

Did she exist at all? The claims of Go Ask Alice always seemed a little flimsy—the author trips on acid and graduates to shooting heroin before ever sampling a cannabis joint—but that didn’t break the spell the book cast on a generation who stayed up all night with what amounted to an urban legend in print. The efforts of prudes to censor the book only transfigured it into something rare: a sermon on temperance that kids longed to read. “It’s like a Chick tract in novel form,” Emerson says.

Over the years, Go Ask Alice fell into a gray area of respectable ill-repute—becoming what Emerson calls “a grubby, strip-mall cousin to The Bell Jar.”

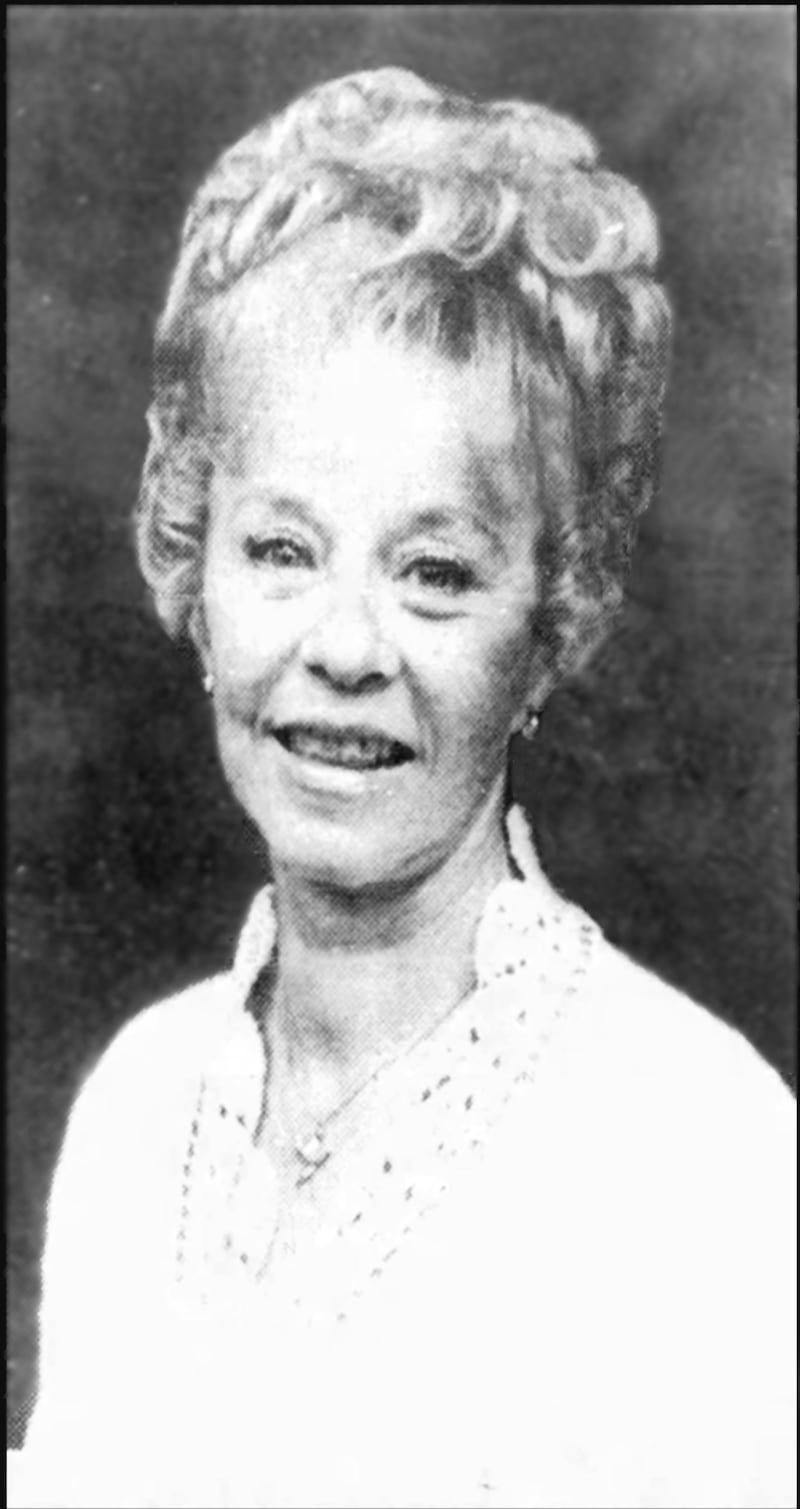

The woman who “discovered” the journals—a Provo, Utah, housewife named Beatrice Sparks—kept producing more diaries. The next one, Jay’s Journal, helped ignite the Satanic Panic, a national hysteria over the occult that lasted for much of the ‘80s. But the more “true stories” Sparks produced of adolescent debauchery, the more likely it seemed she had made Alice up.

Emerson, now 49 and living in Portland, has emerged with the definitive account of just how much of his paperback obsession Sparks fabricated, and how many family tragedies she exploited to reach the bestseller list.

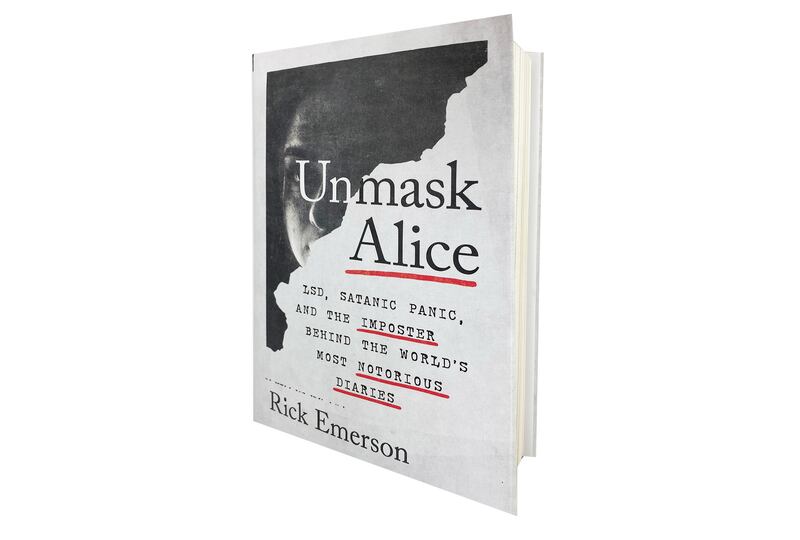

His new book, Unmask Alice (BenBella Books, 384 pages, $26.95), details the number of people in American publishing, journalism and the education establishment who were complicit in the deception—and how the rest were conned.

The result is a propulsive read, a boardwalk thrill ride through the scams and moral panics of the late 20th century that abruptly hits the brakes to consider who’s buried under the fun park. Unmask Alice is an unusually resonant book in the era of QAnon and Pizzagate, when significant portions of Americans are ready to believe their political opponents (and neighbors) are child molesters. And it’s become something of a literary phenomenon this summer, the subject of lengthy consideration in the pages of this week’s New Yorker.

It’s also a second chapter for a man who for 15 years was a familiar voice on Portland radio.

Airing from 1998 to 2012 and drifting from station to station across the AM and FM dials, The Rick Emerson Show was a totem for a generation of Portland pop-culture geeks. With a clipped cadence that recalled the sportscaster Colin Cowherd, Emerson delivered sardonic soliloquies on topics ranging from suicide bombers to the songs of Meat Loaf.

In 2006, WW compared him to Howard Stern (“in the same category, if not class”) and noted that when his show went off the air for a year, devoted listeners mailed Entercom hundreds of coffee cups affixed with notes reading, “I need my morning fix.”

All of which is to say that Emerson knows something about cult followings—both as subject and object.

In 2015, he assumed someone had already written a history of Sparks and her fabrications. An internet search turned up no comprehensive study. Emerson decided to write it. “It is a rabbit hole the length and breadth and width of which I could not have possibly imagined,” he says.

That’s the kind of plunge a lot of obsessive people make—especially if they are, say, adrift after a divorce and the end of a 14-year radio talk show. But Emerson’s fixation revealed a capacity for seriousness he only hinted at on the radio: It took him seven years of research to complete Unmask Alice, and much of that work was spent confronting publishing houses like Simon & Schuster with the damage they did. The book feels like a work of retribution on behalf of anyone who was ever the subject of a nasty rumor.

Not that the myth of Alice doesn’t still hold some power.

“When I was a kid, I was fascinated with the Loch Ness monster,” Emerson says. “And then I reached some age where I was like, OK, there probably isn’t a Loch Ness monster. And then later I’m like, here’s the thing: I’d love for there to be a Loch Ness monster, just because it’s way more interesting.

“And I think that was true with Alice. You kind of want it to be a real diary. That’s just more interesting. Because otherwise it’s just a badly written book.”

The excerpt of Unmask Alice on the following page displays why so many people were willing to ignore their skepticism when Go Ask Alice first appeared.

This passage concentrates on the television star Art Linkletter (yes, the avuncular host of Kids Say the Darndest Things). In 1969, his 20-year-old daughter Diane fell to her death from a Los Angeles apartment tower. Perhaps she jumped. A grief-stricken Linkletter became convinced she was driven to her death by an LSD flashback.

The following year, Beatrice Sparks mailed him a book pitch.

An excerpt from Unmask Alice by Rick Emerson. Copyright ® 2022 by Rick Emerson. Reprinted by permission of BenBella Books, Dallas, Texas. All rights reserved.

1970

For three years, Beatrice Sparks had peppered Art Linkletter with ideas, and nothing had stuck. She was fifty-three, with two grown kids, another in high school, and a string of fizzled projects. Her first book, a self-improvement guide published by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, had sold in Utah County, but just barely.

Then, in rapid succession, everything changed. Diane Linkletter died, and her father became a scorched-earth crusader.

In June, the Manson trial started. All those sweet young girls, warped and destroyed by a monster who fed them acid and stole their minds.

And on October 27, 1970, one year after bringing Art Linkletter to the White House, Richard Nixon got his War on Drugs. Just like that, LSD, mescaline, psilocybin, and even marijuana were Schedule I drugs, right next to heroin.

Beatrice Sparks had found her moment, and she pitched Art Linkletter on a new project: a simple story with a shocking twist.

It was the tale of a bright but troubled California teen. A girl from a good, Christian family. A girl whose parents loved her.

Dosed with LSD by sleazy “friends,” the girl slipped into addiction and chaos. Harder drugs followed, and things got worse. She ran away from home, falling in with outcasts and criminals. Flashbacks came without warning, pushing her closer to madness.

The girl fought to stay clean, but in the end, it was too much. She died without warning, leaving her parents to grieve and wonder.

Then came the real twist. The story was true, the girl left a diary, and Beatrice Sparks had it.

The Bad Crowd, the seduction into drug life, the LSD madness, the death that only seemed like a suicide. It was the perfect pitch at the perfect time. It was, after all, a story Art Linkletter already believed.

In a different state of mind, he might have asked some tough questions. Where was a homeless junkie getting pen and paper, much less storing them? What kind of addict keeps track of a diary, or little jotted notes?

And didn’t the whole thing sound a little too familiar, like a way to leverage Diane’s death?

In the moment, none of it mattered. Of course the timeline was jumbled— junkies were erratic, everyone knew that. And the similarities just proved it was true. You see? It happens. Just like it did to Diane.

And where did Sparks get this diary?

That part changed with every telling, sometimes a little, sometimes a lot, but the basic framework was always the same: Sparks met “Alice” at a youth conference in 1970. The two became friends, and after the girl died, Sparks thought her diaries—properly presented—would be a strong warning about drug abuse.

Sparks had it all planned out. She would cut the diary down to book size, change a few names, and presto—one cautionary tale, ready to sell. She even had a title. Buried Alive: The Diary of an Anonymous Teenager, edited by Beatrice Sparks.

There were a million loose ends. Who was this girl? Where were her parents? Was this even legal? But Linkletter’s reaction was all that mattered, and he was on board. His literary agency, Vandeburg/Linkletter, signed a deal with Sparks, and Clyde Vandeburg, who did most of the agency’s actual work, went looking for a publisher.

Kathryn Fitzgerald stared into the shopping bag. This didn’t look like any book she’d ever seen. There were scraps of random paper and pieces torn from grocery bags, plus a bunch of diary pages, all shoved into a large paper sack.

It was a Friday afternoon in late 1970. Fitzgerald, a twenty-eight-year-old New York native with the beginnings of a nicotine rasp, looked a moment longer, then spoke.

“Let me take it home and read it.”

Fitzgerald hadn’t planned to work in kids’ books—it just sort of happened. She had a finance background, including a stint with the Small Business Administration and four years as a portfolio analyst. Even when she made the jump to publishing, it was strictly grown-up stuff, handling business and finance titles for Prentice-Hall, a company based in northeast New Jersey, across the river from Manhattan.

Still, upward was upward, and when the head of children’s books retired, Fitzgerald sought the position and got it.

Prentice-Hall mostly published nonfiction, and their biggest seller had come thirteen years earlier, with Art Linkletter’s Kids Say the Darndest Things, which (despite the Peanuts-style drawings) was aimed at adults.

Books for children were a different story. They took years (sometimes decades) to gain momentum, then lingered forever, mainly by default. Anne of Green Gables, The Call of the Wild, the Little House novels—they were safe, solid choices, purchased by every new parent or first-year teacher. That was the irony of kids’ books: they were usually chosen by adults.

To make a dent in the young-reader market, a book had to be lucky—and special. So when Clyde Vandeburg pitched what looked like a bag of receipts, Kathryn Fitzgerald was intrigued, but not very hopeful.

A diary. In pieces. Found by some Mormon psychotherapist. Right.

She took it home and started reading. Before long, she was convinced…mostly. Later, the doubts would resurface, and she’d argue against calling it “real,” but the diary felt true, no question. This, she thought, is something special.

Within a few days, things were locked in. Sparks would get a few thousand dollars up front, and if the book was a hit, she’d eventually get royalties. Most books didn’t make it that far, but you never knew. Linkletter’s agency would take 10 percent of Sparks’s end, including the advance. Sparks signed the contact, and Buried Alive was slated for an autumn 1971 release.