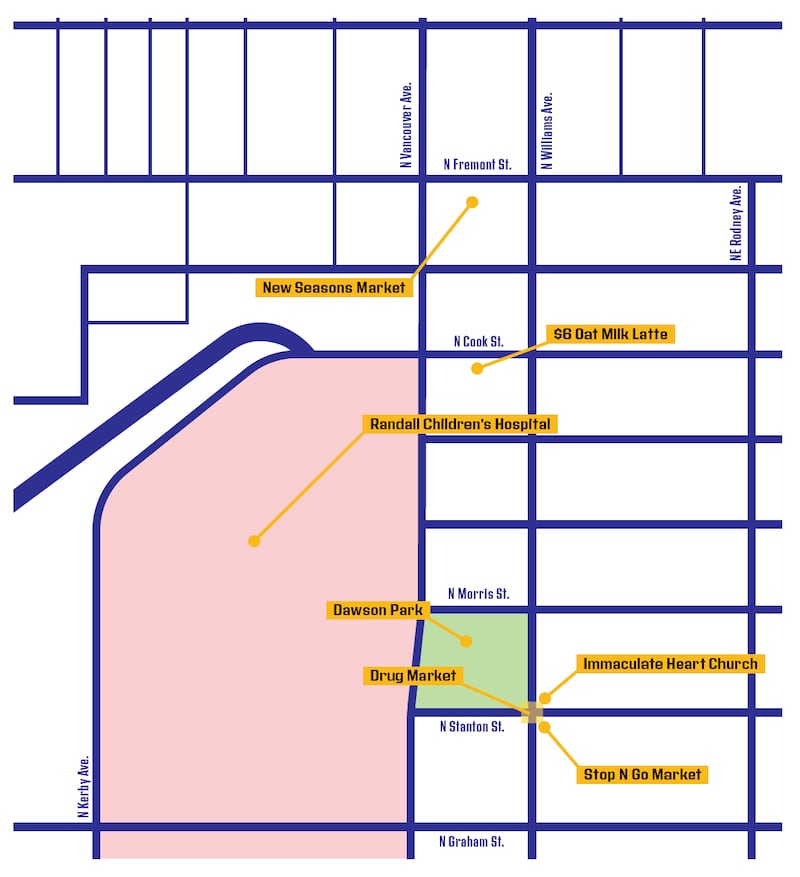

Dawson Park, located in the heart of the Eliot neighborhood in North Portland, is 2 acres of oak trees and green grass. Five blocks away stands a New Seasons and a Pilates studio. Three blocks away, you can buy a $6 oat milk latte. Nearby, an apartment building is charging $2,400 a month for one-bedroom units.

Yet what’s happening on the southeast corner of the park feels a world away.

On North Stanton Street, an open-air drug market sells cocaine to suburban buyers during the day while people smoke crack in the vestibule of a neighboring apartment complex long into the night. Women ask for money from strangers on the corner and, according to a police report, sell sex acts for 20s at the bus stop.

If you’re looking for a social ill that plagues Portland in 2022, you’ll find it here.

For the better part of two years, Dawson Park has made unwanted headlines—never more so than in recent weeks, when Legacy Emanuel Hospital threatened to move its nearby children’s clinic after one of its employees was assaulted. Bullet holes have penetrated the church rectory next door.

These are not isolated incidents of gunfire. The park lies within a zone that city officials have identified in internal documents as the seventh-most likely place to get shot in Portland. Three people have been killed here in two years.

Jason Flakes, who last year moved into a home on Stanton Street with his wife, Brittanie, says his 6-year old daughter, Nya, asks about the people nodding off on the corner. Flakes fears she will pick up discarded hypodermic needles from the sidewalk.

“We have to tell her, don’t be picking up nothing,” Flakes says.

What makes the scene more painful is that it is occurring at a park cherished by Black Portlanders, some of whom travel 9 miles by TriMet bus each day simply to play dominoes in a place that feels like home.

Neighbors, both Black and white, say their calls for help to the city have for years gone unanswered.

The Portland Police Bureau says no targeted drug stings have been made here in at least 14 months. The city hasn’t installed traffic diverters in an attempt to disrupt the drug drive-thru and gun violence. And the park has not been selected as a priority in the city’s campaign to slow gunfire.

In the coming election cycle, candidates across Oregon will describe Portland as a place of danger and lawlessness. In reality, the problems that plague Portland are intense, but they are not distributed evenly across the city. They fester in certain places and affect some Portlanders far more than others.

Over the past two weeks, WW spent time in one of those places.

What we found—both in talking to people who visit the park every day and in reviewing city documents—was the story of a place where city leaders appear incapable of making hard choices. Portland officials reject the unjust systems that resulted in warranted rage and protest two years ago. But they haven’t found something to replace them with.

James Posey, a longtime Black leader in Portland, lives on North Stanton Street. He has for 40 years.

He says Dawson Park “ultimately represents how the city has neglected the Black community.” First, by kicking out Black families. And second, by abandoning the park as it’s beset by crime.

“If you get cops off the record, they’ll say, ‘We’re not going to go over there and police that area because we’re going to be told we’re harassing the Black community,’” Posey says. “And that’s a damn shame.”

To understand what’s gone wrong at Dawson Park, you must understand four factors. Some are old, some are new. But they have converged in this place, and what the city does about them will define how Portland works—and for whom.

Gentrification

Brittanie Flakes, 36, spent much of her childhood in the Eliot neighborhood with her grandmother, who lived there in the 1990s. She remembers drug and alcohol activity in Dawson Park, but her grandma let her play there—it still felt safe.

“As a kid it was like, OK, stay away from the people who are drinking or doing whatever, and you could absolutely go around and play,” Flakes says. “It feels dangerous now.”

The Flakes are Black. That played a role in where they decided to buy a first home. “It was imperative to me to go back and buy property where my family and other Black families were removed,” Flakes says.

Displacement of Portland’s Black community has been a constant.

In 1948, a flood destroyed the largely African American community of Vanport. Many of those Black families and others settled in Northeast Portland, in the Eliot neighborhood—one of seven neighborhoods that collectively make up the historic Albina area. But many of those families were forced to move with the building of Memorial Coliseum in 1960 and Interstate 5 beginning in 1962 and, a decade later, with the 1972 expansion of Legacy Emanuel Hospital in neighborhoods where the Black community had resettled.

In 1970, 9 in 10 Black Portlanders lived in Albina. Now, barely more than 2 in 10 do.

Even with this exodus, parts of North Portland have maintained their significance to the displaced Black community. And, for years, Dawson Park represented that.

Civil rights marches in the 1960s began at Dawson Park. Martin Luther King Jr. visited the playground and spoke at a church two blocks away in 1961. Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy campaigned there in 1968.

“Even when they changed everything, you still come to the park,” says Paul Knauls, 91. Knauls owned a series of businesses, including the Cotton Club, one of Portland’s most famous nightclubs, until it closed in 1970. Strolling through the park in his trademark captain’s cap, he’s still greeted as royalty. On a recent visit, he pointed out the tables across the park, where old men gather with coolers of beer to play dominoes in the shade.

“They still come here every day,” he says, “because this is where their daddy and their grandfathers came to play.”

Royal Harris, a community strategist, was there on a recent Friday afternoon with his grandson. He grew up near the park, until his grandmother’s house was turned into a parking lot. In recent years, he’s organized a series of rallies to bring attention to the problem of gun violence.

That afternoon, a young couple sunned themselves on the grass. Children played on the swings. Men gathered around the domino tables. Says Harris, “What you see is why this park matters.”

To Harris, headlines about crime in the park only reinforce racial stereotypes. “The park is sexy because pathologizing Black men always sells.”

Gunfire

Across from the park is Immaculate Heart Church. Built in 1890, it has welcomed successive waves of newcomers: Irish, German, Black, Vietnamese. But two years ago, it did the unthinkable. Church leaders built a fence, shutting the building off from the neighborhood—and the drug dealers who ply their trade on the sidewalk outside its doors.

Bullet holes have pierced the church twice in recent years, says the Rev. Fr. Paulinus Mangesho. He lives in the neighboring rectory. But, fearing for his safety, he’s taken to sleeping in a back room, facing away from the park.

There’s been three homicides around the park in the past two years. In December 2020, a 53-year-old Uber driver, Kelley Marie Smith, was killed in her car when a gunfight broke out in the park. Three months later, Titus McNack, 42, was shot multiple times on the sidewalk outside the park on a busy Tuesday in broad daylight. Both of those homicides are unsolved. Prosecutors declined to comment about them, citing ongoing investigations.

A year later, Mark Johnson, 55, was killed in the road near the park by Joseph Kelly Banks, who had schizophrenia. Banks had killed two other people already, and all three murders are believed to have been random—in other words, Banks hadn’t known his victims.

Gun violence has risen nearly everywhere in Portland since 2019, not just in Dawson Park and not just in Black communities.

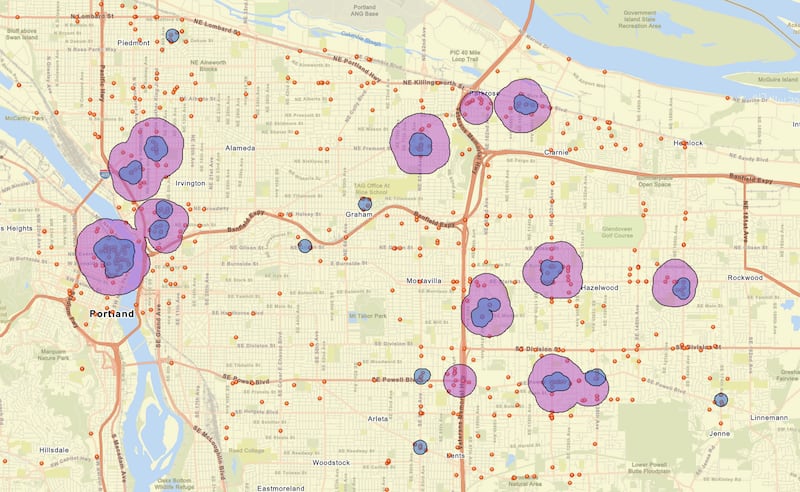

Still, a map provided to WW by the city’s Community Safety Division shows the area around Dawson Park ranks seventh on a list of 18 gun violence “clusters” identified by the city this summer.

Calls to police from the neighborhood appear to be rising, slowly. In 2012, around 14 out of every 1,000 dispatched calls for help came from Eliot. By 2022, that number had risen to 18.

In recent years, suspects have been prosecuted for firing guns into the park’s trees, beating up a prostitute soliciting at the nearby bus stop, and stealing a 2-year-old out of a stroller.

Mangesho blames city leaders for not doing enough to protect the neighborhood. “They hear, they see, and they don’t act,” he says.

Drugs

While it’s arguable whether the area around Dawson Park is that much more violent than the rest of the city, few neighborhood streets see as much drug activity as the southeast corner of the park.

On a Thursday afternoon, a WW reporter witnessed five drug deals on the Stanton Street side of the park within an hour. A young white man pulled up in a new gray Mercedes Benz. He stepped out of the car, ran to the dealer’s car, exchanged money for product, and drove away along Williams Avenue. The exchange took less than 30 seconds. The dealer moved inside the park, lounging against a public trash can as he casually executed the next four deals.

Those familiar with the market say the drug is cocaine, but fentanyl and meth can be found here too, according to court records.

On a recent warm night in September, two women and a man huddled in the vestibule in the shadow of a neighboring church and smoked a crack pipe.

The men on the corner drift in and out of the Stop N Go Mini Mart on the corner. The man behind the register keeps a gun prominently displayed on his hip. He declined to discuss what happens on Stanton Street.

Drug dealing near Dawson Park is not new, even if its scale has increased since the pandemic descended and possession of small amounts of hard drugs were decriminalized in Oregon last year. It’s a place where a Portland Police Bureau Street Crimes Unit once conducted investigations of “open-air narcotic trafficking,” a unit that was disbanded in 2020 amid staffing shortages.

And while the bureau does have a Narcotics and Organized Crime Unit, the bureau says it’s a “very small unit” now, and the North Precinct has done no targeted drug busts in the past year, according to Tina Jones, commander of the precinct.

Jones says police have increased patrols in Eliot but don’t have the staff or the time to target dealers, let alone invest in the community policing that neighbors are demanding. “We’re just putting out fires everywhere,” she says.

The Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office has not prosecuted a single person for dealing cocaine in 2022, data provided by the office shows. There’s been a steep decline in the charge in recent years. In 2018, prosecutors charged 71 people. By 2020, it had fallen to 12 and, in 2021, to nine.

While the DA’s office declined to prognosticate why prosecutions have dropped so steeply, spokeswoman Elisabeth Shepard says the DA’s issuance rates are a “reflection of referrals” from police, and referrals have decreased over the past two years.

Police Bureau spokesman Lt. Nathan Sheppard says: “I would imagine between staffing levels greatly reducing the size of specialty units and the advent of Measure 110, our ability to investigate drug-related crimes has been greatly diminished.”

Cmdr. Jones says such arrests are complicated by Measure 110, which decriminalized possession of small amounts of hard drugs in 2021. The DA’s office says recent changes in Oregon case law have made it harder to punish known drug dealers.

“We’re not able to obtain the sentence that a reasonable person would expect,” says deputy district attorney Eric Palmer.

City Inaction

For close to two years, residents of the neighborhood have begged city officials to quell the drug dealing and gun violence along North Stanton Street. For two years, they’ve been told the city doesn’t have the resources to help.

City officials say they’re mostly focused on addressing gun violence in East Portland.

“It is clear from the map that outer East Portland is the part of the city most impacted by gun violence,” says Lisa Freeman, programs manager for the Community Safety Division. “We also know that many residents of outer East Portland feel disconnected from and neglected by the city.”

Nearly every person WW spoke to in and around Dawson Park said it feels as if City Hall doesn’t care about them.

“I don’t know how the city truly feels about it, but it’s scary you can lose your life and the city will say oh well, that’s just how it is,’” says Joseph Young, who grew up in Eliot, played basketball in Dawson Park as a youth, and still lives in the neighborhood with his family.

It’s not that the city doesn’t spend money on the park; in 2013, it spent $2.7 million alongside private partners to rehab the park. It’s currently renovating the basketball courts. Boulders etched with the park’s history, funded by the city, sit in the center of the park.

But what most neighbors want is for the city to show that drug dealing and gun violence along Stanton isn’t welcome.

The city says it’s taking actions it can within funding limits: The Office of Violence Prevention contracts with groups that “conduct outreach in and around the park,” says Freeman, and it supports events hosted at the park. The parks bureau increased ranger visits at Dawson Park in response to gun violence and because it had funding for more rangers across the board.

Meanwhile, the Community Safety Division funded three nonprofits beginning in August to reduce gun violence at Dawson Park and other places (see “Keeping the Peace,” below).

A 2019 email reviewed by WW shows that when the Police Bureau decided to prioritize Dawson Park that year, it backfired: “Several community members became upset about the project before it really even got started,” a police captain wrote at the time, adding that the bureau’s approach to the park after the backlash “changed dramatically. Through this process we have identified areas within the [bureau] where we ourselves need to improve. Some of these areas are centered around providing further education to our officers about the history of Dawson Park.”

Cmdr. Jones says police conduct is “scrutinized at all these different levels,” including through a racial lens.

“We’re not just going in like we would a couple decades ago and saturate the area and stop everyone,” Jones says. “We have to factor in whether we’re going to be overpolicing.”

She says it’s a priority of the bureau as it beefs up staffing over the next few years to figure out what Portlanders want from their police force. “I think it’s really important to make sure we’re working with the community about how they want to solve some of these problems.”

It’s not just the police that neighbors have gone to for help. Since 2020, they have begged the Portland Bureau of Transportation to install a traffic diverter or calming device that would make it harder for drug dealers to sell along Stanton and would help quell gun violence.

According to emails obtained by WW, PBOT told neighbors they needed to bring in more Black voices before it would make any changes.

“The key to any improvements in this area will be a coalition that specifically includes Black Portlanders,” a bureau staffer wrote in November 2020. “Particularly for something as potentially divisive as restricting auto access to a street (and one that leads directly to a key community gathering place like Dawson Park), we’ll need to include more Black voices into the proposal.”

In March, City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty’s office and the Community Safety Division held a meeting at Matt Dishman Community Center. They acknowledged the area has been ravaged by gun violence.

Young calls the meeting “the biggest shitshow I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Neighbors at the meeting tell WW the calls for more policing—even when it came from Black residents—went unacknowledged, particularly by Hardesty’s staffer.

“I heard my Black neighbors asking for appropriate policing in this neighborhood,” recalls Cassie Muilenberg. “A nuanced conversation around policing was just not welcomed.”

Hardesty tells WW she supports more policing in places where violence is high, but that it “must adhere to the Constitution and not engage in racial profiling or criminalizing people just for hanging out in a public park.”

She adds: “Violence and drug trafficking have been occurring in this area for a long time, but it’s just now getting more attention as the area becomes more gentrified.”

Mayor Ted Wheeler, who oversees the Police Bureau, declined multiple requests for an interview this past week. His office did not say why.

Instead, mayoral spokesman Cody Bowman says: “We know we have work to do in Dawson Park and other areas around the city that are experiencing a disproportionate level of crime in the city. We will continue our efforts until we see results.”

Neighbor Brittanie Flakes says what’s being done just isn’t enough.

She and Nya were walking home from school last week when they approached Stanton Street.

“She says, ‘Oh, Mommy, I hate walking through all these people,’” Flakes recalls. “I said, ‘Nya, you have to remember that you live here. These other people do not. You have every right to be here.’”

Keeping the Peace

If there’s hope for Dawson Park, it may look like Lionel Irving.

On a recent Friday afternoon, Irving met up at the park with two of his business partners, Troy Ramsey and Talmage Ellis.

The three of them once repped different gang colors in the streets, before spending decades behind bars for their crimes.

Now, the trio contracts with City Hall through a nonprofit called Love Is Stronger, which holds events in the park. They received a $201,000 grant from the city this summer.

“We’re positive influences. We’re violence interrupters,” Irving says. “We’ve come to build relationships, and we capitalize on relationships we already have with guys on the street.”

Former gang members themselves, the three maintain an unspoken rule for Dawson Park: Dealers stay on the corner, known shooters stay out.

Some say it’s working. “It’s changed a lot: calmer, quieter, not a lot of violence. Especially when you guys are here,” a man in a yellow suit says, gesturing at Irving. He, like most of the regulars at the park who spoke at length with WW, declined to give his name.

The goal, Irving says, is making the park a welcoming place for everyone—the grandparents who grew up down the street, and the young families that just moved in.

“We used to own these homes, and now we don’t.” Irving says. But, he adds, “They’re not going anywhere. And we’re not leaving either.”

This article was published with support from the Jackson Foundation, whose mission is: “To promote the welfare of the public of the City of Portland or the State of Oregon, or both.”