Not everyone knows how a combustion engine works. But few people avoid cars because they can’t describe in detail how gasoline ignites, drives pistons, and creates forward motion.

Melanie Billings-Yun, former co-chair of the Portland Charter Commission, says people should think of ranked-choice voting with multimember districts the same way as their cars. That’s the perspective she recommends voters take when they consider whether to approve a new structure for city government on Nov. 8.

You don’t have to know exactly how it works, just that it does.

The new charter proposes linked changes that would each be big on their own—and many people are hung up on the new voting method in particular. Among them is Oregon state Rep. Rob Nosse, a Democrat from deep-blue Southeast Portland. Last week, Nosse said he planned to vote no on charter reform in part because, after reading the description, he doesn’t understand exactly how it would work.

“It does not read like the candidates who get the most votes win,” Nosse wrote in The Southeast Examiner. “I think that is a recipe for suspicion and mistrust. How votes are counted and who wins must be straightforward, especially in a rank choice system.”

In short, Nosse wants to know more about how the car works before he gets in it.

We at WW did, too. First, we called a number of experts, including a college professor who has just written a book on voting reform, a software guy who has been studying this stuff for years (election methods pretty much are all math), a die-hard advocate for ranked-choice voting, and Billings-Yun, twice.

They were tough conversations. They featured terms like “droop quota” and “surplus fraction.” And almost everyone sent us off to watch videos that featured cartoon characters or Post-it notes and sing-song narrators guaranteeing that this stuff really works.

Along the way, we learned the history of ranked-choice voting. It was big during the Progressive Era, from the 1890s to the 1920s, when people became enraged at party bosses and disillusioned with democracy. The first ranked-choice elections may have taken place in Washington state in 1907, according to Jack Santucci, a professor at Drexel University in Philadelphia, who just this year published More Parties or No Parties about election reform.

At one point, Santucci says, there were 98 states and localities using some form of ranked-choice voting. Then, the parties reasserted control, people got fed up with the complexities, and almost all of those places gave it up. Only two, Cambridge, Mass., and Arden, Del., have kept it going since before World War II.

Others have implemented it since then, certainly, as Portland proposes to do. Minneapolis adopted it in 2006. Benton County, Ore., jumped on board in 2016. Alaska used it for the first time this year. It’s big overseas, too, in Australia, Ireland, Scotland and elsewhere.

The goal of ranked-choice voting is to capture the greatest possible expression of voter sentiment and seek as much consensus as possible. If you have one vote in a race for City Council, and your candidate loses, your sentiment was barely expressed, and there is little consensus. RCV, as it’s known, also seeks “proportional representation,” meaning that the demographics of the elected body match the demographics of the electorate.

Portland reformers hope to do that by having four geographic districts with three city commissioners each. They say that combination ensures that candidates who wouldn’t have a chance in a two-way race, but have a large constituency, might still end up in office—without being spoilers.

In short, you could vote for Ralph Nader without torpedoing Al Gore.

Even after all the interviews, though, we still didn’t really understand ranked-choice voting. So we held a series of mock elections in our office, using beloved fairy-tale characters like Mother Goose and the Big Bad Wolf as the candidates. (We hope they’re beloved. Send complaints about the choice of fairy-tale characters to my editor: amesh@wweek.com.) It involved cutting up scraps up of five colors of paper and stacking them three high to simulate three choices for one district. Each pile became a vote. Then, we followed the rules to see how the ballot of an average voter, we’ll call him Thomas Lauderdale, would fare if he picked the Tooth Fairy, Gretel and Mother Goose, in that order.

The secret sauce in ranked-choice voting with multimember districts is that votes don’t die after one round. They are recycled through several rounds of counting, doing more work to express voter sentiment, and to build consensus, with each round.

This is called ranked-choice voting with a “single transferable vote.” What that means: Each voter has one vote, and it can transfer to a second or third choice if the voter’s first choice is defeated early.

And once Mother Goose gets enough votes to win a seat, her “surplus” votes also get shared with others because she doesn’t need them!

We’re printing the results of our mock election here, with descriptions of what happens in each round of counting.

We hope our play-by-play will make things clearer. It took us hours to figure out how this car really runs, and we’re still picking up paper scraps. But we’re pretty sure it works as advertised, if you just want to rank your picks and drive off the lot.

Scenario 1: A blowout, in which Thomas supports the front-runner, the Tooth Fairy.

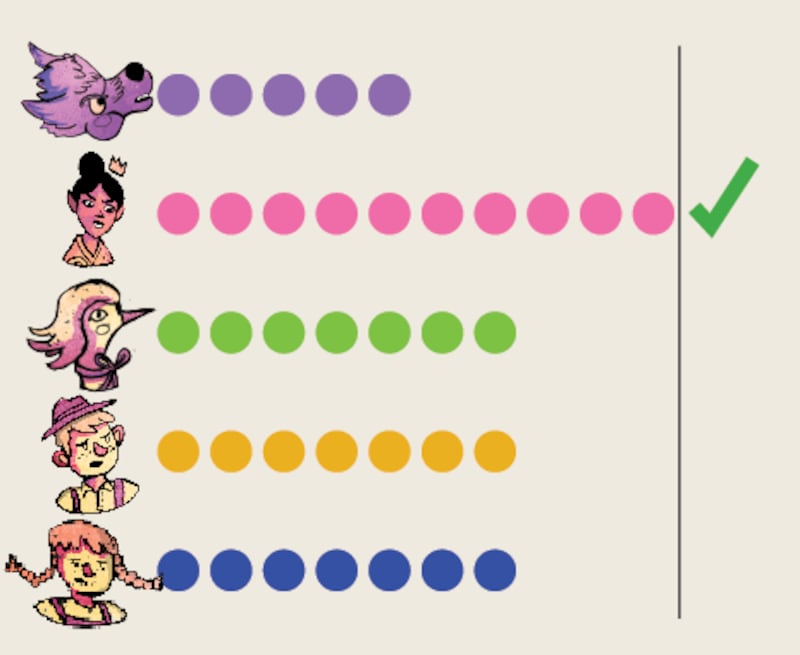

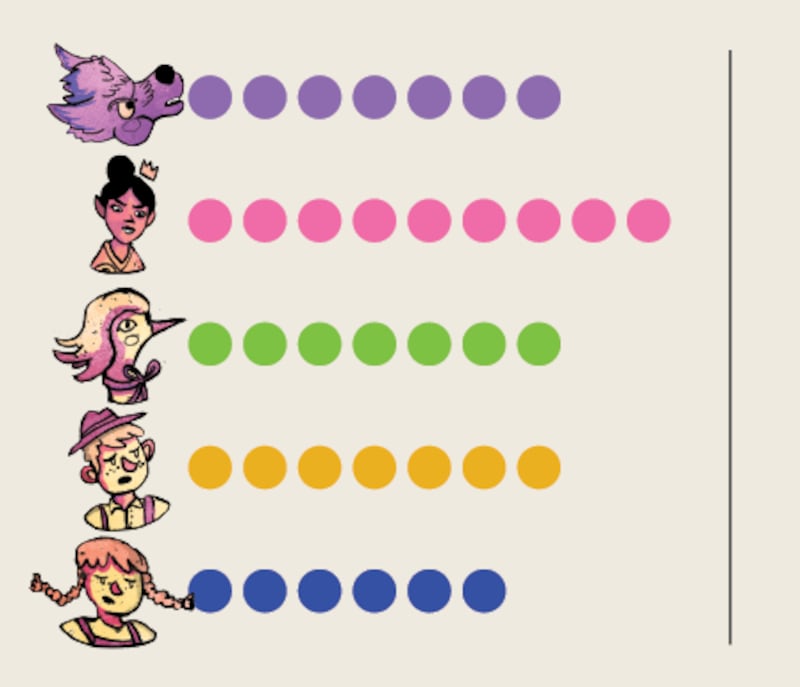

Round 1: With three spots available in this district and 36 voters, a candidate needs 10 votes to win a spot on the City Council, or about 28%. The Tooth Fairy clinches a spot in one round of counting! No other candidate does.

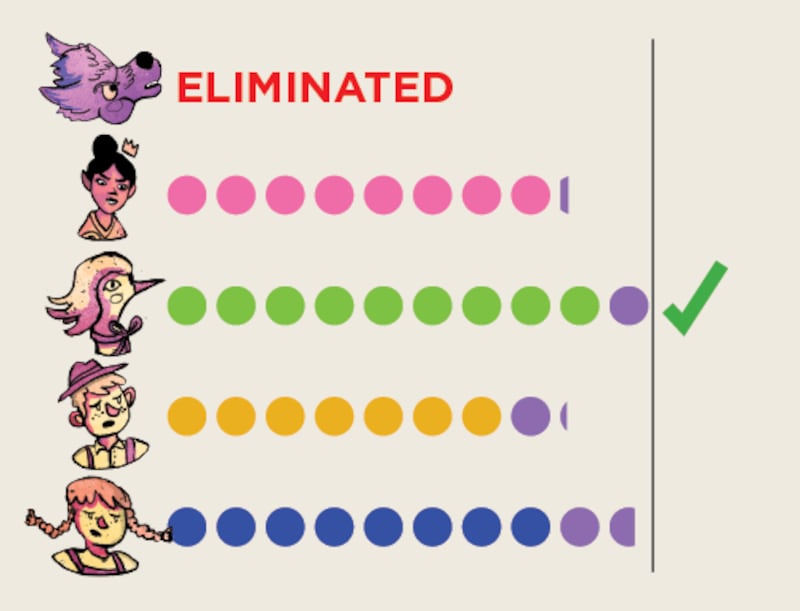

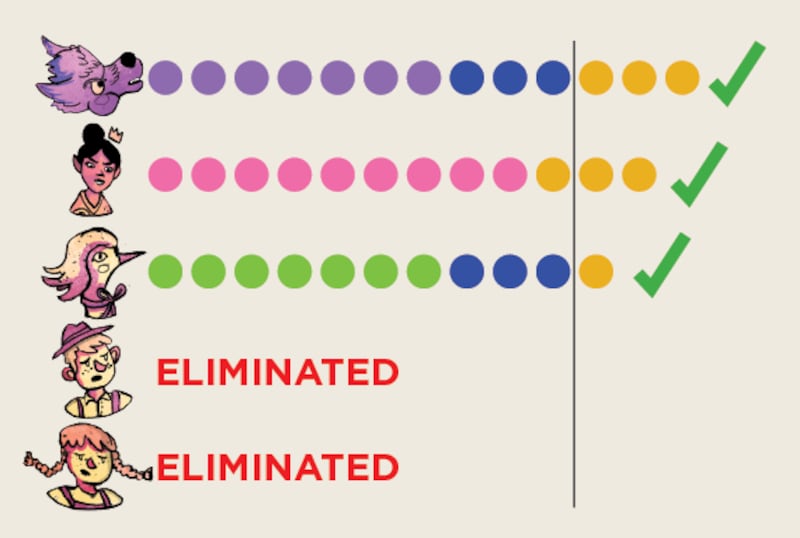

Round 2: Among the remaining four, the candidate with the least votes is eliminated. That’s Big Bad Wolf, with five. Voters who had him as their first choice now get their second choice. Hansel gets another vote, and Gretel gets four more, pushing her over 10.

Round 3: Mother Goose is eliminated. Voters who chose her first get their second choice, but it doesn’t matter because only three remain: the Tooth Fairy, Hansel and Gretel.

Result: Thomas Lauderdale sees his first and second choices elected, but his third doesn’t make the cut.

Scenario 2: A tight race.

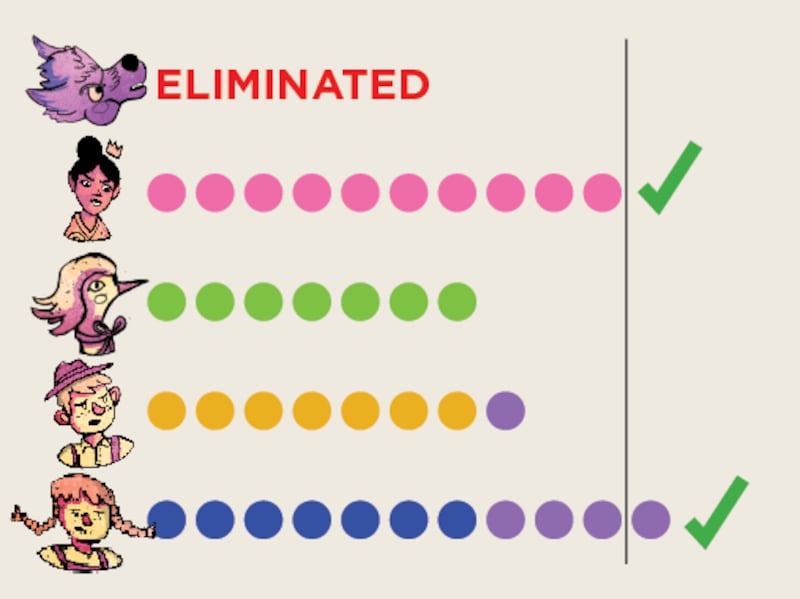

Round 1: No candidate gets 10 votes, so there is no winner, yet.

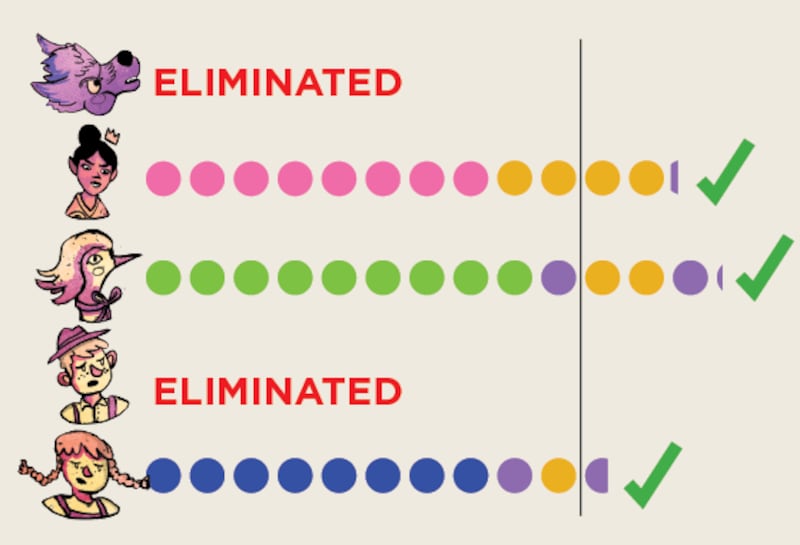

Round 2: Big Bad Wolf, with the least votes, is eliminated. Second-choice votes on those ballots are allotted to Mother Goose (2), Hansel (1) and Gretel (1). Mother Goose gets to 11, more than enough to win.

Round 3: This is where it gets trickier. Mother Goose has more than enough votes to win—by one vote—so that one extra vote is divvied up among the 11 voters who chose Mother Goose so they can send it to their second choice. One divided by 11 is 0.09. Only one voter who chose Mother Goose first chose Hansel second, so he collects 0.09 of a vote. But seven voters who chose Mother Goose first chose Gretel second, so Gretel gets 0.63 of a vote (7 times 0.09). All the excess votes have been distributed, and still no one besides Mother Goose has hit 10, so we have to cull the herd again.

Round 4: Hansel has the least votes, 8.09, and he is eliminated, leaving the Tooth Fairy and Gretel, who pick up Hansel’s second-place votes and win, both because they have enough votes and because they are among the last three.

Result: All of Thomas’ choices are elected!

Scenario 3: Just so we get this.

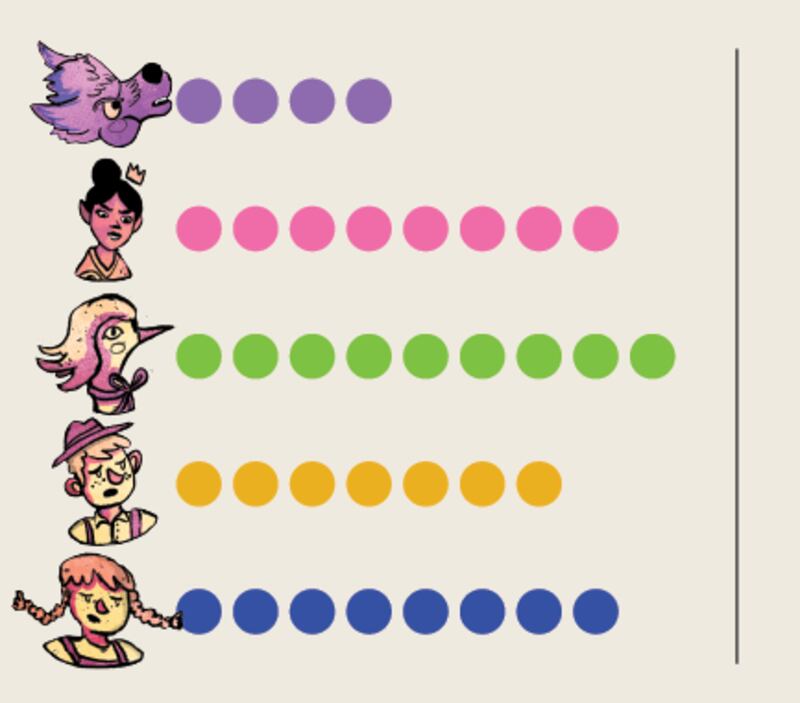

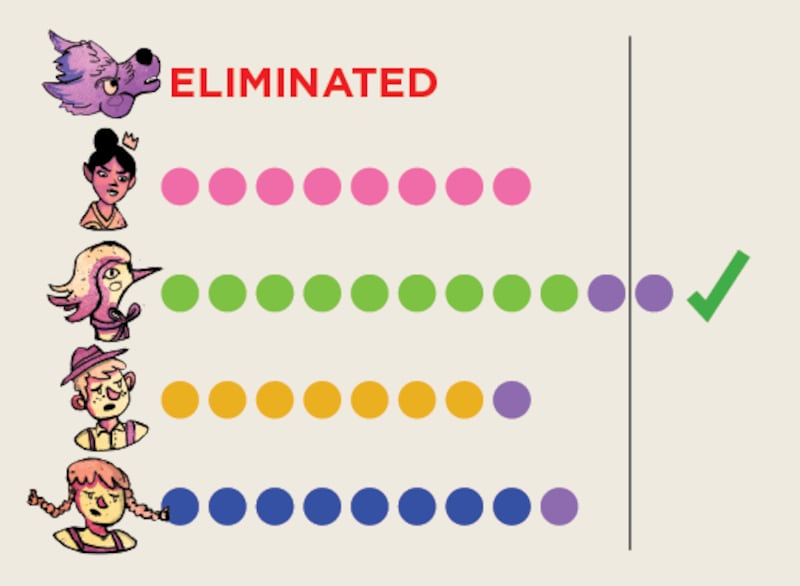

Round 1: Again, nobody gets 10 votes, which they need to claim one of the three seats on the council, so we go to…

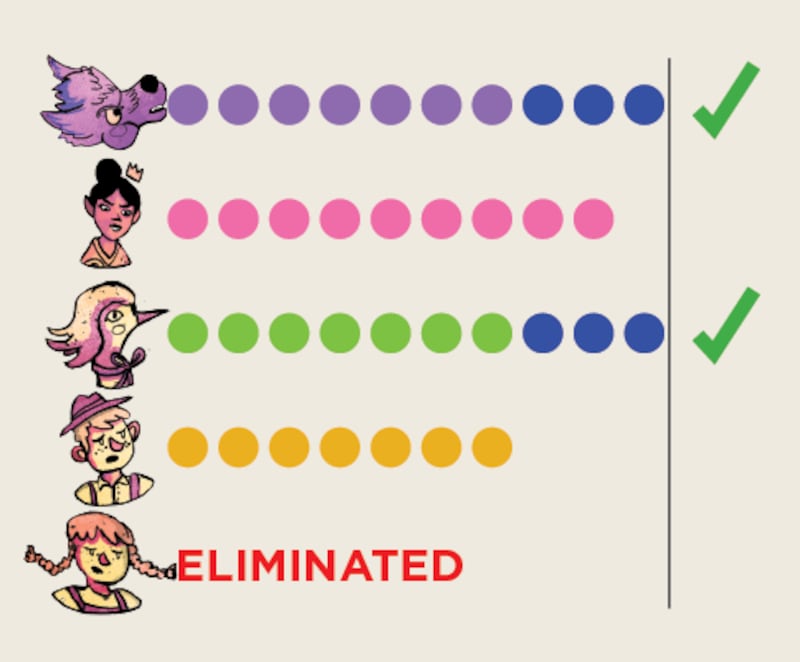

Round 2: Gretel, with just six votes, is eliminated. The second-choice votes on those Gretel ballots are passed to the other candidates, giving Big Bad Wolf and Mother Goose three more each. No one who chose Gretel first chose Hansel second, so he picks up no new votes and stays at seven.

Round 3: Hansel is eliminated and his votes are redistributed, leaving Big Bad Wolf, the Tooth Fairy and Mother Goose as winners.

Result: Thomas’ first choice, the Tooth Fairy, and his third choice, Mother Goose, are elected. His second choice, Gretel, loses. Poor Gretel! But Thomas feels enfranchised!