Just a few decades ago, treasure hunting in the Pacific Northwest was a family pastime.

Load the kids and the pickaxes into the station wagon and hightail it into the hills, seeking lost mines on any given Saturday. Trek out to Manzanita to look for the fabled Neahkahnie beeswax shipwreck. Or make a car camping trip out of it: Spend a few days digging in the Eastern Oregon desert for forgotten gold caches.

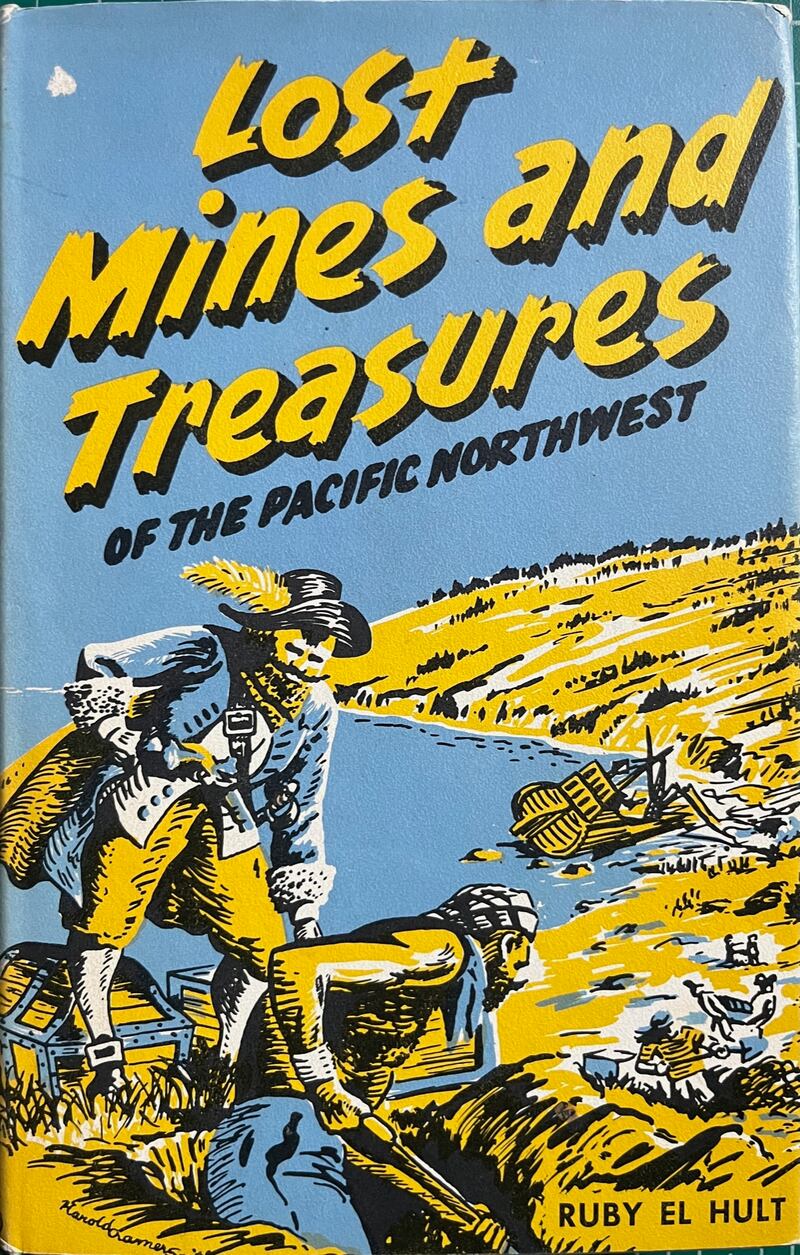

The mid-20th century rise in weekend treasure hunting had a good bit to do with popular historian Ruby El Hult. Her 1957 book, Lost Mines and Treasures of the Pacific Northwest, offered readers a sweeping catalog of lost hoards hidden in old barns, down abandoned mine shafts, and under tree stumps across Oregon, Washington and Idaho.

So many of El Hult’s readers decided to leave their armchairs and head out with their shovels that she published a sequel volume, Treasure Hunting Northwest, in 1971. This was filled with tips and updates from fans who had gotten the treasure bug from her earlier book.

Hidden treasure is the talk of Oregon again this year, after researchers found the sea cave where that beeswax shipwreck might rest (“Weird Summer Tales,” WW, Aug. 3).

But what if we told you another storied treasure lies somewhere in Portland?

One of El Hult’s stories focused on the Portland Treasure Chart, a map to a cache of Civil War gold purportedly buried somewhere in the Rose City. The fact that El Hult dubbed this one “Big City Treasure Most Popular of All” in her follow-up book testifies to its allure.

Nobody ever found it. What we propose is: You can.

Over the summer, your correspondents—both local historians—hit upon a new Portland location to search for the lost gold. It’s up in the West Hills just off Highway 26 in the historic Jones Pioneer Cemetery.

That’s right: treasure hidden in a cemetery! Who says Portland is over?

Before we tell you more about what to do when you get there (besides NOT digging in a fucking cemetery, of course!), let’s lay out the story.

“My object has been to keep the facts straight and not confuse the reader by fictionalizing, embroidering, dramatizing, or otherwise doctoring up the tale, even when it is bald, short and incomplete.”

—Ruby El Hult, Lost Mines and Treasures of the Pacific Northwest, 1957

WHAT’S BURIED:

$6,000 in two graves. Might be gold!

THE STORY:

In 1933, Seattle judge Everett Smith died. Among his possessions: a treasure chart, sometimes dubbed “Sims’ Gold.”

Drawn on waxed “kitchen paper” with pricey artist crayon (not the common Crayola variety!), the chart likely dates from some time between 1890 and 1920, Portland paper expert John V. Henley tells WW. While some have observed that it looks like a kid’s rendition of a treasure map, the detailed and meticulous nature of the Treasure Chart indicates a more intentional design.

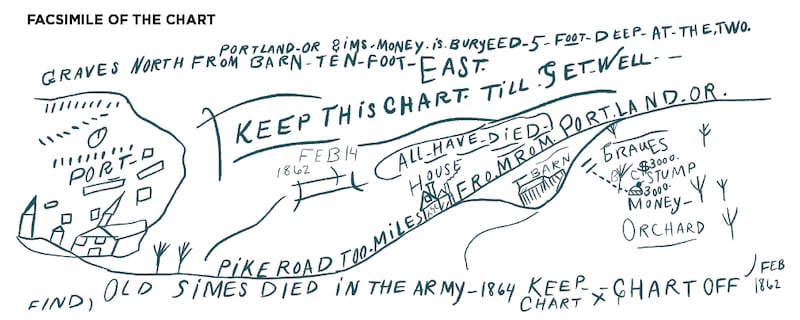

WHAT THE CHART SAYS:

Written across the chart in blue crayon is the following:

“PORTLAND OR. SIMS MONEY is BURYEED 5 FOOT DEEP AT THE TWO GRAVES NORTH FROM BARN TEN FOOT EAST.

KEEP THIS CHART TIL GET WELL

ALL HAVE DIED

PORT

PIKE ROAD TOO MILES FROMROM PORTLAND OR

GRAVES $3000 $3000

TO FIND

OLD SIMES DIED IN THE ARMY 1864 KEEP CHART. CHART OFF. FEB 1862.”

On the left side of the chart around the word “PORT” are sketches of buildings, including several with spires and a small blue circle that some have interpreted to represent a pond or lake. From the left edge, extending across the chart, is a line, with the words “PIKE ROAD TOO MILES FROMROM PORTLAND OR.”

Moving toward the right side, a house appears above the line and below it, a barn—along with the word “GRAVES” and two points at the end of a dotted line each marked “$3000.” The barn, house, a big stump, and an orchard are labeled in yellow.

Because the treasure is labeled “Sims’ Gold,” the established thinking is that a Civil War-era soldier named Sims or Simes left the chart as a kind of last will. In one 1966 retelling of the tale, “the treasure had been buried by two men headed for the Civil War. The men died in action, but not before drawing the chart and writing the mysterious and cryptic legend.” Where they got all this information from the chart is beyond us, but it makes for a pretty kickass story.

PREVIOUS THEORIES ON THE TREASURE’S LOCATION:

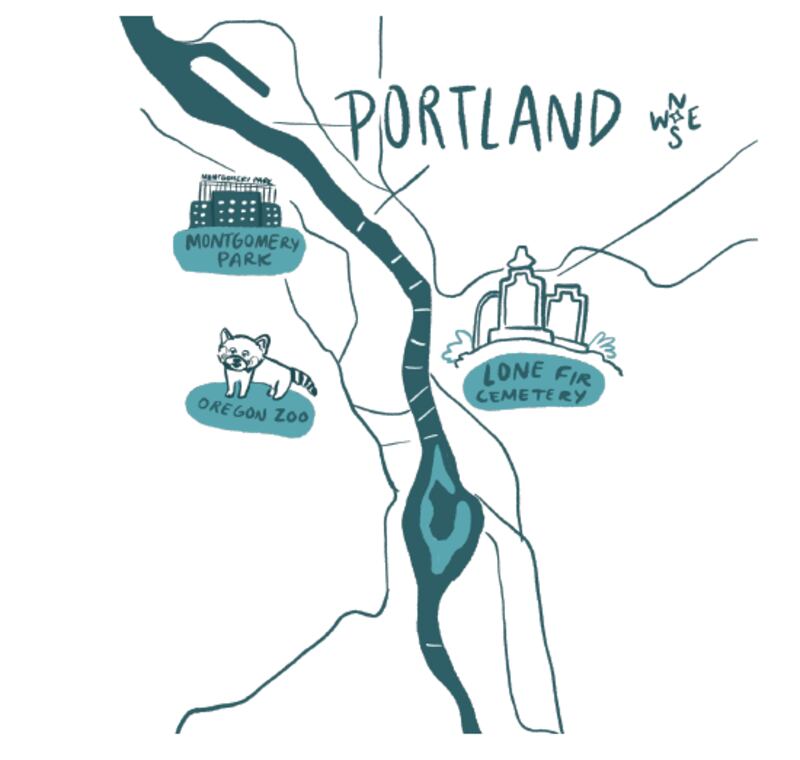

Shortly after his father the judge died, Irving D. Smith grabbed a shovel and his inherited chart and headed for Northwest Portland’s Montgomery Ward building (today known as Montgomery Park and home to the Adidas store).

Presumably, he based the location on the idea that Portland appears on the left side of the map and that the road across the document doesn’t cross any river. Two (written “too”) miles from Portland would put him basically at Montgomery Ward. Whether he found graves there or the money, for that matter, is unknown since no record of his search has been located.

Smith passed his treasure chart on to the Oregon Historical Society, where it was filed away. But El Hult’s first treasure book in 1957 prompted all sorts of Portlanders to resume the search.

Many of these treasure seekers would write down their ideas, with pen or typewriter on paper, and mail these missives to El Hult. And she would often write them back! Many of these correspondences are collected in the archives of Washington State University in Pullman.

There was a husband-and-wife team, whose interpretation of the map took them to “the new Zoological Gardens” in Portland’s West Hills.

There was the Burgess family, who, with their four kids, three dogs, pet monkey and pet tarantula (true story), geeked out on the possibility that the words on the chart had hidden meanings. They took “fromrom” to mean Roman Catholic and sought out a Catholic church in Southwest Portland. They followed Southeast Belmont Street to Lone Fir Cemetery exactly 2 miles from Mount Tabor, looking for graves marked “Sims,” “Simes” or even “Graves.” They couldn’t find any.

Then there was Ronald L. Gluth, who was convinced that the $6,000 was in the form of “Beaver Money.” (These were solid gold coins minted in Oregon City in 1849 to simplify financial transactions in an era when beaver pelts and sheafs of wheat were used for trade.) Gluth also set his sights on the Portland Zoo as a possible spot for the $6,000 treasure. As Gluth explained in a letter to El Hult: “It would appear that if I can’t pinpoint the exact spot in a very short time it will be impossible to get to as the country is blowing its cool trying to pave the whole area for a new freeway. So I had best get with it.”

It’s not clear if he got with it. The Portland Treasure Chart faded into oblivion.

OUR NEW THEORY:

In 2022, co-author of this story JB Fisher hit on a new lead while attending his stepfather-in-law’s funeral. Fisher noticed a Pike Road right here in Portland, leading up to a cemetery.

And that graveyard happens to be on the property of a zany old pioneer hermit who was brutally and fatally assaulted by men who were convinced that he had money hidden on his land.

On the day of the assault, he had just returned from Portland, having completed a $6,000 property transaction. And get this: At the top of his cemetery, not far from where his house and barn once stood, one headstone marks two graves.

His name was Nathan B. Jones, and he arrived in Portland in 1847 with his father from Salem, New Hampshire. Jones took a 342-acre donation land claim at the head of Tanner Creek in the area today known as Sylvan in the West Hills.

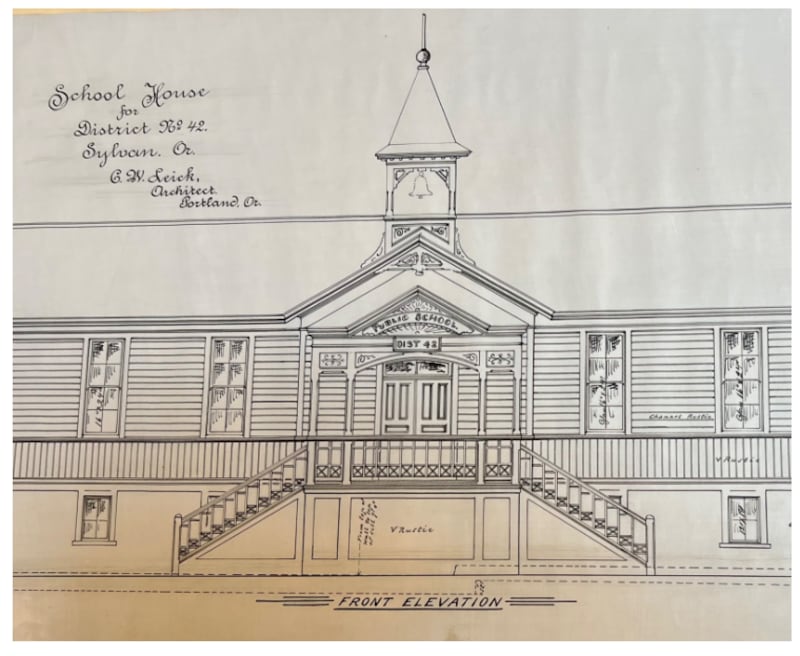

Jones and his dad William had big plans for the Sylvan area. They named it “Ziontown,” and a community rose up complete with saloons, a general store, a schoolhouse, and an 11-building property occupied by the Jones duo known later as the Hermitage.

William Jones died in 1854, and his son buried him on the property. But that didn’t stop the big plans. Nathan B. Jones wanted to make Ziontown the new capital of the United States. He hoped to request $10 million from the U.S. government and had large murals (in “psychedelic colors,” according to Oregon chronicler Ralph Friedman) painted on the outside of his buildings, showing what the glorious new U.S. Capitol in the West Hills would one day look like.

In reality, Jones couldn’t even get a Ziontown post office. Instead, the community was renamed Sylvan after postal officials determined that the name Ziontown would be confused with similar names of other places in Oregon.

Defeated and getting older, Nathan B. Jones lived out his days in his rustic Hermitage, buying drinks for young ruffians at the local saloons and reluctantly selling off very small parcels of his land, all the while stubbornly retaining much of his original donation land claim (which wasn’t exactly legal).

Thus, when he was brutally assaulted and died a week later in 1894, the community wasn’t too sad to see him go.

As The Oregonian reported following the assault, “Someone entered his house and beat him over the head with…probably a club, inflicting a long, deep, and dangerous wound…” The paper also noted that Jones had sold some of his land for $6,000, and the belief among neighbors was “that it was this money that the robber expected to get.”

A local character named Charles Davey was tried but not convicted of Jones’ murder. Nathan B. Jones, unloved dreamer and would-be founder of a new empire, was buried alongside his father, William Jones, in what would soon be known as Jones Pioneer Cemetery.

The treasure chart first surfaced 29 years later. It listed a Pike Road leading 2 miles from downtown Portland to $6,000 in two graves.

Is there such a road? In January 1851, work began on Canyon Road from Portland to the Tualatin Valley via Ziontown. It’s memorialized by a bronze marker in the South Park Blocks, right between the Oregon Historical Society and the Portland Art Museum—a smidge more than 2 miles east of Jones Pioneer Cemetery.

To this day, there’s no evidence that anyone has found any money on the Ziontown property.

But why give up hope when you can enjoy a weekend treasure trip?

GETTING TO JONES PIONEER CEMETERY:

Take the Sylvan exit (exit 71) from Highway 26 west from Portland or east from Hillsboro. Turn south onto Southwest Scholls Ferry Road. Turn left at Humphrey Boulevard just south of the highway and then right on Hewett Boulevard. Turn left into the Westside Vineyard Church parking lot. The cemetery entrance is at the end of the parking area. NOTE: DO NOT PARK IN THE CHURCH PARKING LOT. DRIVE INTO THE CEMETERY AND PARK ON THE SIDE OF THE ROAD.

WHAT TO DO AT JONES CEMETERY:

Drive through the cemetery gates and park along the circular drive. Take a moment to look around. The area surrounding the circular drive is the newer Jewish cemetery established by Portland’s Havurah Shalom congregation in 1986.

- Walk around the circular drive to a brick path heading into the old pioneer side of the cemetery. Turn right onto this path and head north (toward the traffic noise of Highway 26).

- As you start, you will notice three obelisk markers to your left. One of these is for Ida Hansen, who at age 15 killed herself in 1909 by drinking carbolic acid when her parents told her she couldn’t go out with friends one night.

- Continue about 20 paces (yes, we are using paces because this is a treasure hunt!). Come to a large monument labeled “Aken” to your right. This is for Robert Aken, a friend and neighbor of Nathan B. Jones who accompanied him to Portland and back on the fateful day that Jones was assaulted. Robert Aken’s son is also buried here (unmarked but confirmed by his 1950 obituary in The Oregonian). “Young Aken” was a local hoodlum who specialized in beating up and robbing old men in the area.

- Continue on the brick path as it turns to the right and snakes its way east toward the top of the cemetery.

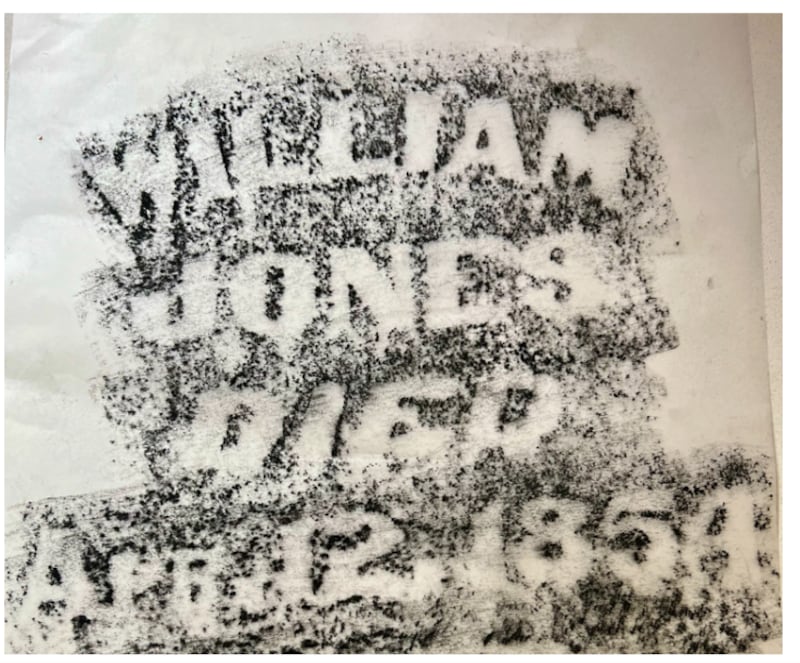

- Before the brick path ends, take a right and cut across the cemetery about 30 paces toward the largest maple tree in the immediate vicinity. Beyond this, you will find a towering gravestone marked “Jones” at the base.

- This is the shared marker of Nathan B. Jones and his father, William Jones, and it also commemorates the founding of Ziontown in 1850.

- Head 10 paces northeast to find a small obelisk marked “Alva Elroy Hunter” on one side and “Oscar Hunter” on another. Oscar was born and died Aug. 3, 1875. Alva was born March 26, 1878, and died Aug. 23, 1879.

Look around. Notice the houses on the other side of the fences just beyond the graveyard. These stand on the location of Nathan B. Jones’ sprawling 11-building “Hermitage.” Now, notice the large hedge dividing the pioneer cemetery and the newer Jewish cemetery. Jones had a barn and an orchard, and they likely stood in this area.

The Portland Treasure Chart notes: “MONEY is BURYEED 5 FOOT DEEP AT THE TWO GRAVES NORTH FROM BARN TEN FOOT EAST.” Does this mean that the $6,000 is buried at the Hunter graves? Who knows, but it’s a pleasant view!

In 1894, the Hunter obelisk and only a few other stone monuments would have been present here.

The drawing on the left side of the Treasure Chart shows what appears to be a pair of obelisks and a building with a steeple on the opposite side of “Pike Road.” The steepled 1893 Sylvan Schoolhouse stood on the other side of Canyon Road (now Highway 26) where today’s Odyssey Program school building stands.

In 1894, there were far fewer trees and the steeple would have been clearly visible looking northwest.

So maybe the drawing on the map shows the view from where the treasure lies buried!

But maybe not. There is nothing in the Jones story to do with old soldiers named Sims or Simes dying in the Union Army in 1864.

For old Civil War-era soldiers, you would need to go elsewhere. Lone Fir Cemetery in Southeast Portland would be one option. Another would be the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery off Southwest Boones Ferry Road. There are plenty of Civil War soldiers there, although the oldest grave dates from 1881.

We can’t emphasize this enough: Don’t dig up a cemetery.

As Ruby El Hult reminded those naughty readers who may have contemplated digging up hallowed ground:

“I warn readers who may follow the clues and locate the graves that the jail sentence for disturbing this cemetery will be a long one—at hard labor, I hope!”

—Ruby El Hult, Treasure Hunting Northwest, 1971

WHAT YOU CAN DO INSTEAD OF GOING TO JAIL FOR DESECRATION OF A GRAVE SITE:

Make a gravestone rubbing

Take a stroll through the graveyards listed in this story and you’ll stumble across hundreds of eye-catching gravestone designs. While you can always take a picture of them, you could instead release your inner teenage goth and make some striking art.

What you need:

• Lightweight paper, such as newsprint, rice paper, or vellum tissue paper

• Rubbing wax, a large crayon, charcoal or chalk

• Paint tape or masking tape

How you do it:

• Gently brush off the gravestone of any loose materials such as pine needles and leaves (Note: Don’t scrub or scour gravestones!)

• Affix the lightweight paper to the front of the gravestone with the paint or masking tape.

• With the wax, large crayon, charcoal or chalk, start rubbing in a side-to-side motion either from the outside of the gravestone toward the inside or from the top to the bottom.

• When finished, detach the paper, discard the tape, and voilà! Instant Halloween decoration for next October!

Bring a picnic

Pack your favorite pinot grigio or IPA (or both!), throw in some snacks, a blanket, and rain gear and you are good to go! Note: Be considerate of graveyard inhabitants. Don’t picnic on top of them!

Grab some refreshments at a nearby establishment

Not a fan of sitting on the ground fending off yellowjackets and raindrops? There are plenty of watering holes and eating establishments around each of these locations. Below are a few favorite featured cemeteries, a few tips that might place them within the Portland Treasure Chart, and some select eateries.

Jones Pioneer Cemetery, 5763 SW Hewett Blvd.

Skyline Restaurant: Since 1938, this place has been serving burgers, shakes and other drive-in favorites. The sign says “Best Burger in Portland” for good reason. James Beard proclaimed this when he ate here in 1975. 1313 NW Skyline Blvd.

Gigi’s Cafe : Formerly a food cart, Gigi’s boasts “the best waffles in the universe,” and its sweet and savory selections live up to the hype. Can’t decide what to order? Try one of the impressive waffle flights. 6320 SW Capitol Highway

Cornell Farm Nursery & Cafe Not just a fourth-generation family farm and nursery, it’s also a delicious brunch destination. Biscuits and tasso gravy, right-out-of-the-oven cinnamon rolls, avocado toast and eggs Benedict. 8212 SW Barnes Road.

Montgomery Park, 2741 NW Vaughn St.

Not a gravestone in sight, but one of the first locations searched for the Sims site. Worth a look.

Great Notion Brewpub: Love IPAs? Sours? An affinity for Ken Kesey? This is the place for you! Tasty smash burgers and other pub fare, too. 2444 NW 28th Ave.

Sasquatch Brewery and Taproom: Another great beer destination. 2531 NW 30th Ave.

Fuego Cart: Yummy burritos and bowls. We recommend the chicken bowl with cheese. 2701 NW Vaughn St.

Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery, 9002 SW Boones Ferry Road

Civil War veteran graves galore, as well as a few big stumps.

Boulevard Taphouse: Try the fish sandwich, some housemade chili tots, and one of the 14 rotating beers on tap. 7958 SW Barbur Blvd.

Spunky Monkey Coffee Kitchen: Stop in for great coffee, breakfast sandwiches and more, but bringing your family’s pet monkey is gauche. 7900 SW Barbur Blvd.

Lone Fir Cemetery, 649 SE 26th Ave.

Plenty of 1860s tombstones for you to consider, and a bevy of historic Portlanders lie here, including Asa Lovejoy and Daniel Lownsdale.

Bare Bones Cafe & Bar: Halloween-themed cafe and bar just a stone’s throw from the cemetery. How convenient! 2908 SE Belmont St.

Bluto’s: The latest from the Lardo folks, serving tasty Greek-inspired classics and spot-on cocktails. 2838 SE Belmont St.

Canteen: If you need to reenergize with fresh juice, a smoothie, or a wholesome salad or bowl, this is the place to go. 2816 SE Stark St.

ForeLand Beer: More great beer. Oh, and it’s a 2021 Oregon Beer Awards Best New Brewery winner. Sit here and mull the mysteries that lie beneath Portland lost to time. 2511 SE Belmont St.

“I only wish I could figure out a few more things that puzzle me about that chart. I think there is probably just one thing in there that is the key to the whole thing and if a person finds that they will be able to figure the rest of it out. There is something about that chart that bothers me and I wish I could put my finger on it.”

—Ruth Burgess, amateur Portland treasure hunter, in a letter to Pacific Northwest history author Ruby El Hult, 1967

About the authors:

Doug Kenck-Crispin is the Resident Historian for the podcast Kick Ass Oregon History. JB Fisher is author of Echo of Distant Water (2019) and co-author of Portland on the Take (2015). Together, they are working on a film about the Neahkahnie treasure tales.