Multnomah County recently released its first annual report on its use of the $2.5 billion Metro homeless services measure voters approved in 2020. That money will go to the three Portland-area counties over 10 years to alleviate homelessness.

In its annual report, Multnomah County explained the outcomes the new money produced: “The Joint Office [of Homeless Services] used [supportive housing services] dollars to provide emergency shelter services to 357 people, place 1,129 people [962 of whom were chronically homeless] in housing, and prevent evictions and homelessness for 9,156 households,” wrote JOHS interim director Shannon Singleton. (The placement of 1,129 in housing fell just short of the county’s goal of 1,300. Keeping people housed exceeded the goal.)

One other data point: The number of people living unsheltered in the 2022 point-in-time count increased 50%, or by just over 1,000 people, from 2019.

All that can make assessing results confusing. The agency’s budget offers clearer points of comparison.

The agency spent significantly less than planned.

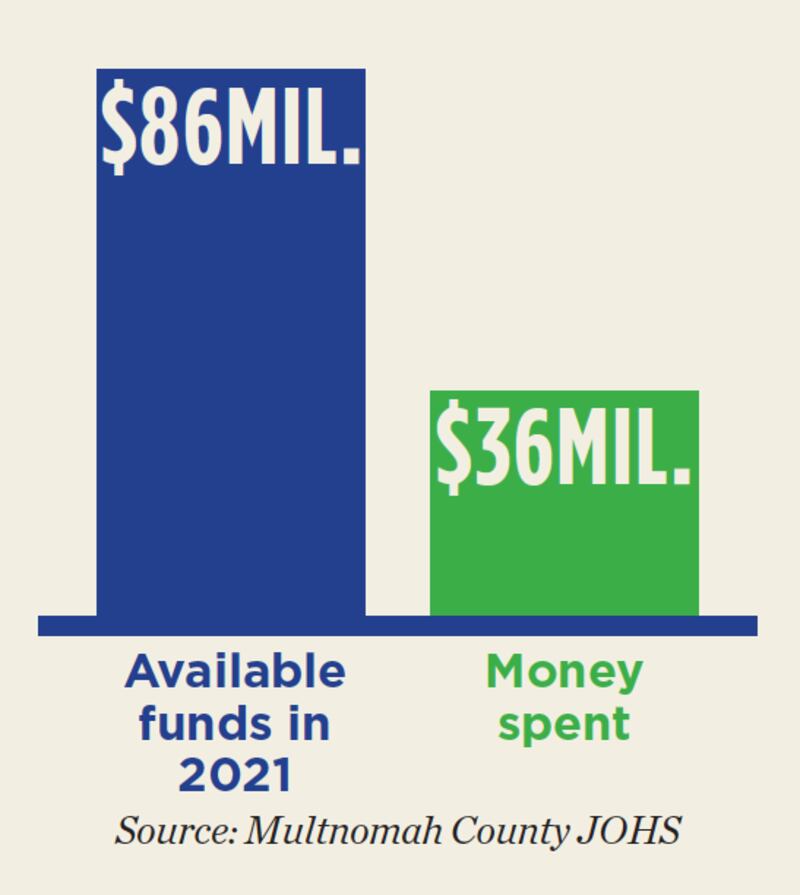

The Joint Office budgeted to spend $52 million from the Metro measure in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022. But by then, it had spent just $36 million, about 70% of what it planned.

That underspending looks even more dramatic when compared to the amount of money actually available—Metro bumped the forecast up to $68.4 million available midyear and actually collected $86 million for Multnomah County. That means JOHS spent far less than it could have (it will roll those extra dollars into this year).

Joint Office spokesman Denis Theriault says starting up a new program proved difficult.

“That requires time spent contracting with service providers, building up capacity to process a massive influx of new funding, and hiring frontline workers to take on the new work,” Theriault says. “Hiring was particularly challenging this year, same as in other sectors of the economy, but exacerbated by the reality of frontline work in a difficult field that requires being on the ground in a pandemic.”

Tom Cusack, a retired federal housing official who blogs about housing, is tracking the spending of the Metro funds. Cusack notes that JOHS is off to a very slow start for fiscal 2023, spending only 7% of its budget in the first quarter of fiscal 2023.

“That means they have to spend 93% in the next three quarters,” Cusack says. “I just don’t know how they are going to do that.”

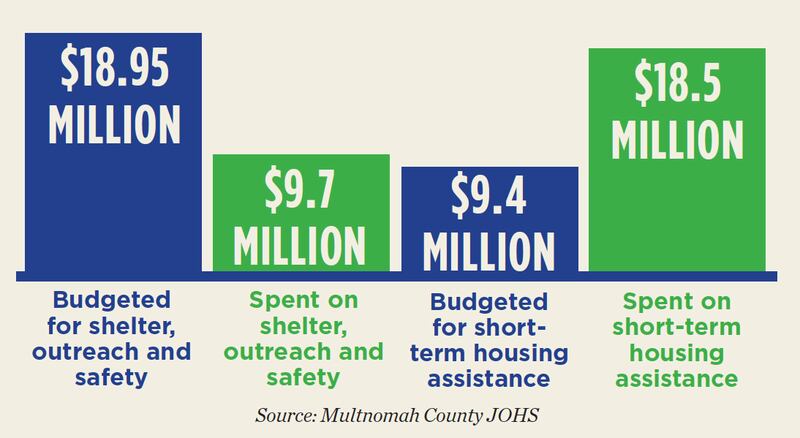

The agency spent its money far differently from its budget.

For instance, the agency’s budget shows it spent disproportionately on “short-term housing assistance,” allocating $18.5 million, or twice its budget on that expenditure.

Meanwhile, spending on “shelter, outreach and safety on/off the street” and “permanent supportive housing services” was $9.7 million, less than half the budget.

That prioritization did far more for people with existing, if precarious, homes than for those who are unsheltered and in need of the services supportive housing provides.

Patricia Rojas, director of housing at Metro, says the spending reflects what was possible in a short time. “It takes more time to identify a housing unit and connect services required,” Rojas says. “That’s a lot more work than short-term assistance, which might just be cutting check.”

Polls show voters want to see visible improvement on the streets.

Theriault says it’s a matter of what can be done with limited staffing. “Shifts among the spending categories reflect the reality of getting dollars out the door overall,” he says. “If one program or service area is still ramping up but another area can scale up with additional funds and serve more people, then there’s flexibility to do that.”