The scandal enveloping the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission involves a vanishingly small percentage of the $839 million worth of hard liquor the agency sold last year.

In fact, OLCC director Steve Marks, who resigned at Gov. Tina Kotek’s request Feb. 15, had lost the job he held for nearly a decade even before Kotek learned that Marks and five top agency managers had admitted diverting rare and precious bottles of Pappy Van Winkle whiskey (mostly bourbon but also some rye) for their own use and for the use of others, including as yet unnamed state lawmakers.

Records the OLCC has released so far—originally in response to a request by The Oregonian—show managers who were either dismissive or willfully ignorant of state ethics laws that prohibit public officials from using their positions for personal gain (in this case, whiskey that is worth 10 to 20 times on the open market what is charged by Oregon liquor stores, and is not generally available to the public).

On Dec. 22, OLCC compliance director Rich Evans found after an internal investigation that Marks and five of his top managers had each “abused his public position for personal gain.” (A sixth manager not implicated in the scandal, CFO Kailean Kneeland, lives far from OLCC stores, in Arizona.)

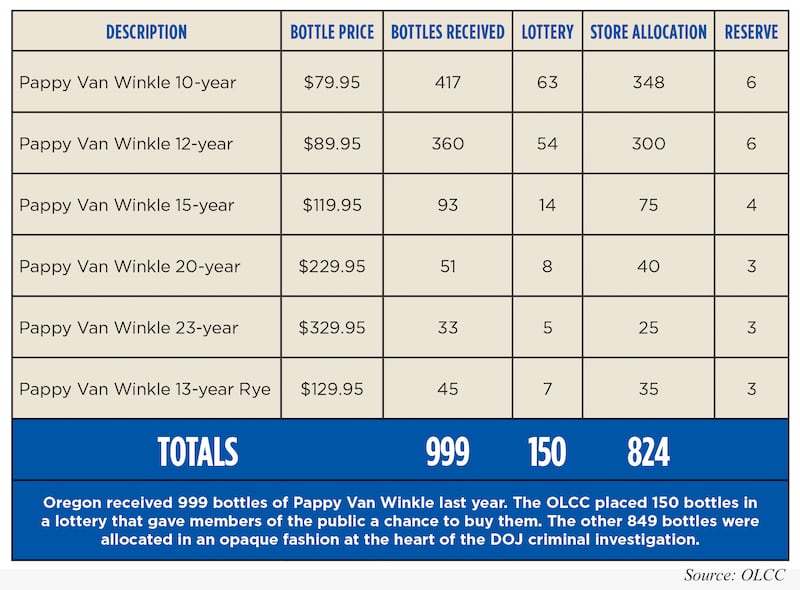

Records newly obtained by WW show just how rare the whiskey is. The agency sold 44.35 million bottles of liquor last year. Fewer than 1,000 of those bottles—or 0.0023%—were the Pappy Van Winkle brand. (While the bottles allegedly set aside also included Elmer T. Lee, that brand is less desirable than Pappy.)

Yet the Pappy may have put the agency’s future in jeopardy. Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum announced Feb. 10 that she’ll conduct a criminal investigation into where those bottles went and how they got there.

The answers could do more than just shed light on agency management, some observers say: They could give the Northwest Grocery Association the ammunition it needs to convince voters it’s time to privatize liquor sales.

“People can quickly and easily understand this scandal,” says Jim Moore, a professor of political science at Pacific University. “It’s less self-serving than the grocers’ argument that it will bring more bodies into the store. In campaign terms, this fits on a bumper sticker.”

Here’s what led to the scandal: