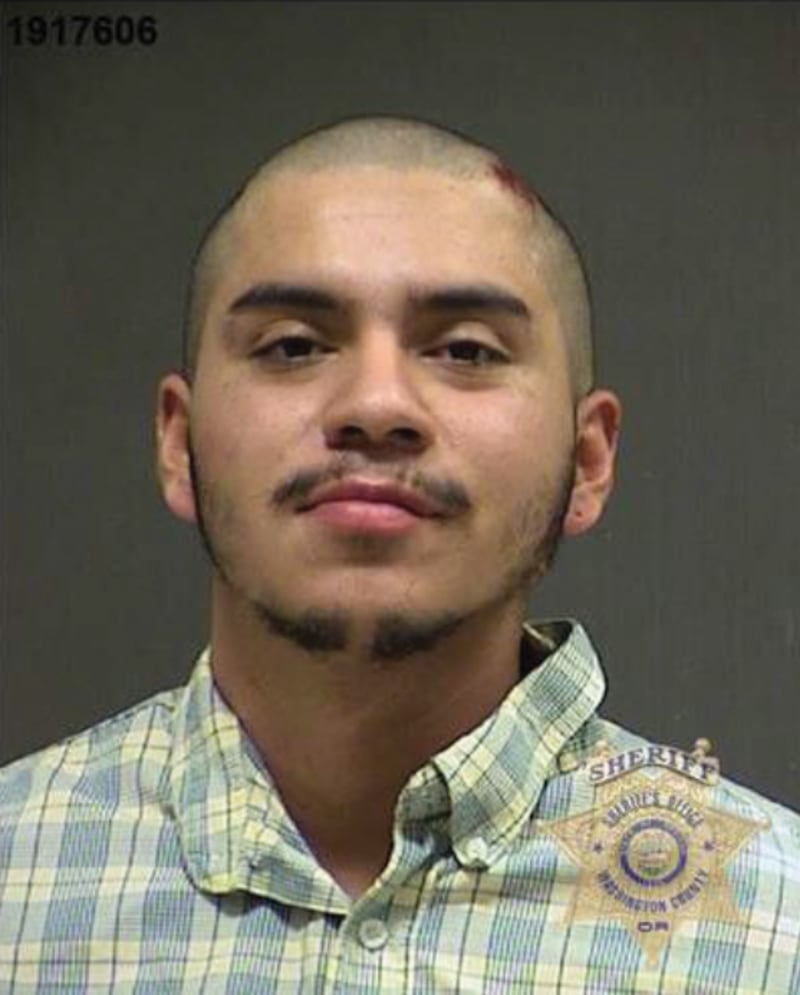

One morning, a week before Christmas 2019, Salvador Martinez-Romero arrived at Murrayhill Marketplace in Beaverton.

The tidy suburban shopping center, set amid towering Douglas firs, oozed a holiday peacefulness.

That disappeared in a heartbeat.

Martinez-Romero, broad-shouldered with a mustache and patchy beard, still shy of his 21st birthday, came to Murrayhill Marketplace on Dec. 18 not to spend money—but to get it. He brought a chef’s knife into the Wells Fargo Bank branch and robbed it. Inside the bank, he stabbed two women, injuring 53-year-old Debra Thompson and killing her 72-year-old mother, Janet Risch.

He then walked outside, clutching fistfuls of cash. He encountered Ian Day sitting in his car. Martinez-Romero stabbed Day twice, then stole his Chevy Impala and drove into the residential neighborhoods of Tigard, where he stabbed another woman and ran, chased by police.

When police finally caught up with him, Martinez-Romero barked at their K-9 dogs. A judge later said there was evidence he was high on methamphetamine at the time.

Terrible crimes occur everywhere, even in well-manicured suburbs. But what happened that day at Murrayhill Marketplace would launch Martinez-Romero on an odyssey that highlights the deep dysfunction of Oregon’s mental health system.

Oregon’s number of residential psychiatric treatment beds per capita is about average compared with other states. But the state also has one of the highest rates of mental illness. The result: Four out of 10 Oregonians with serious mental illness are not getting treatment, according to analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

After his arrest, Martinez-Romero sat in the Washington County Jail for two months. During that time, his attorney says, he was not of sound mind and, at least once, attempted suicide.

In February 2020, a judge deemed Martinez-Romero unable to assist in his own defense and sent him to Oregon State Hospital, the state’s locked psychiatric facility in Salem. The goal: that he be “restored to competency” to stand trial.

Last month, he was sent back to Washington County after spending three years at the state hospital, which is so strained by the skyrocketing number of mentally ill criminal defendants sent there that it recently limited patients judged incompetent to stand trial to a maximum stay of one year.

The state hospital is the tentpole at the center of Oregon’s mental health system. Records show it is overburdened and wildly expensive. Martinez-Romero’s three-year stay at the hospital, for instance, cost around $1.5 million. He made little progress and occupied a scarce treatment bed for which nearly 100 other severely mentally ill patients languished on a waitlist.

Doctors failed to eliminate Martinez-Romero’s persistent self-reported delusions, according to court testimony, and nurses suspected he was malingering. Prosecutors argued Martinez-Romero was sufficiently competent to face trial. On Feb. 2, a judge agreed, sending Martinez-Romero back to jail to await trial set for next year.

In other words, his hospitalization provided little benefit at great expense.

Cases such as Martinez-Romero’s and overcrowding at the state hospital have created a crisis of epic proportions. Although the Oregon Legislature is now rushing to fund improvements, critics say state leaders have allowed the situation to deteriorate for too long.

“It’s a human-made problem,” Washington County District Attorney Kevin Barton says of the forced release of patients. “The state hospital is inadequate to meet the need. The hospital has known that for years. The Oregon Health Authority has known that for years. And now we’re paying the consequences.”

To find a time when Oregon’s mental health system actually worked, Jason Renaud, co-founder of the Mental Health Association of Portland, says you need to go back to the beginning.

In 1861, Dr. James Hawthorne opened the Oregon State Insane and Idiotic Asylum in what was then the standalone city of East Portland. “He recognized that these were illnesses and that people can be treated with compassion,” Renaud says. “It’s been going downhill since.”

Lawmakers eventually moved Hawthorne’s patients to a new hospital in Salem in 1883.

That facility, Oregon State Hospital, is the primary treatment center for “aid and assist” patients such as Martinez-Romero—people who are charged with crimes but deemed too mentally ill to stand trial.

Over the years, the state hospital weathered criticism for keeping patients in inhumane conditions and applying abusive treatment methods. The 1950s saw the beginning of a nationwide movement to “deinstitutionalize” the mentally ill, placing patients in community programs that experts say are more effective, more humane—and much cheaper.

But Oregon’s investment in community programs didn’t keep up with the need—leaving few alternatives to the locked-down psychiatric hospital it has repeatedly downsized. The Oregon Health Authority reported in early 2022 that the state was short 480 licensed residential treatment beds, about a quarter of the capacity needed in community programs. The state has funded less than half of that 480-bed deficit.

At its peak in the 1950s, when the state’s population was less than half what it is now, Oregon State Hospital held more than 3,500 patients. But that number plummeted thanks to civil rights-era reforms, and has hovered at 600 to 700 for more than a decade.

The state considered expanding the hospital’s capacity when it rebuilt the Salem campus and added a Junction City satellite in the early 2010s, but advocates convinced lawmakers not to, arguing the money was better spent on community-based services.

The state then failed to invest sufficiently in those community services, which allow patients to receive care nearer their homes and in less restrictive surroundings.

Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem), who championed rebuilding the hospital and retired last year, says state leaders failed to prioritize the issue after building the new facility. “We got complacent,” he tells WW.

Oregon has the nation’s highest prevalence of mental illness, according to a 2022 report by Mental Health America. And its access to care ranks in the bottom half of states.

As a result, the state hospital is overflowing. As of January, there were 98 criminal defendants awaiting a bed. Greg Roberts, superintendent of the state hospital at the time the new Salem and Junction City campuses opened, tells WW nobody should be surprised at the current state of affairs.

“To the extent that your community mental health system is robust, then you can rely less on a state hospital,” Roberts says. “But to the extent that your system is not robust, the state hospital starts to become the only game in town.”

Administrators say one answer to the hospital’s overcrowding would be to add more beds. But lawmakers have repeatedly rejected that solution, focusing instead on community services that rarely materialize.

State. Rep. Rob Nosse (D-Portland), who chairs the Oregon House Committee on Behavioral Health and Health Care, says community facilities are less expensive, closer to patients’ families and, unlike the state hospital, often covered by Medicaid. “We need to ensure that when people are ready to leave OSH,” he tells WW, “they have somewhere to go.”

Nosse has also noted that the state hospital is struggling to recruit and retain staff, a problem that also limits community programs’ capacity.

Last fall, the shortage of beds at the state hospital and in Oregon communities reached a breaking point. Under pressure from judges and advocates, the state resorted to releasing more defendants from the hospital before they were sane enough to go to trial.

“This revolving door of people offending, being held, released and reoffending is taking a toll,” Eugene Police Chief Chris Skinner told lawmakers in December.

Originally, Oregon State Hospital existed to serve three groups of patients: those who had been tried for a crime and found guilty except for insanity (GEI); patients charged with a crime but unable to aid and assist in their own defense because of mental illness; and patients who had not committed a crime but had been civilly committed because a judge found that they presented a danger to themselves or others or were unable to take care of their basic needs.

During the past decade, “aid and assist” patients such as Romero-Martinez have outstripped all patients in the other two categories.

In 2000, less than 10% of the state hospital’s beds were taken by aid-and-assist patients. Now, it’s nearly 60% (see “OSH Average Daily Population,” below). It’s such a daunting figure, people who have been civilly committed now often go to emergency rooms instead. That is overwhelming local hospital systems, which aren’t equipped to serve such patients.

The state’s housing shortage has exacerbated the challenge of providing community mental health resources. And the pandemic ratcheted up the stresses both on patients and the state’s mental health workforce. All of those factors increased pressure on the state hospital. “It’s kind of a perfect storm,” says Bob Joondeph, who ran the nonprofit advocacy organization Disability Rights Oregon for 30 years before retiring in 2018.

Joondeph remembers when the state bused people with mental illness back to Old Town from a state hospital campus in Wilsonville. Now, that campus is closed and Portland’s cheap housing has largely disappeared. As new condos replace single room occupancy apartments, many people struggling with mental illness now live on the streets.

“It’s reverted to the way it was 40 years ago,” Joondeph says. “Except now, there’s even less housing.”

By 2022, Oregon’s mental health system was a tinderbox. Last September, a judge in U.S. District Court in Portland threw a match on it.

As part of federal litigation suing the state’s mental health system, Disability Rights Oregon pointed to a 20-year-old court order requiring that people with mental illness who were charged with a crime should stay in jail no longer than seven days before they were sent to the state hospital. State officials admitted they were failing to meet that standard.

“We’ve run out of good ideas,” then-Oregon Health Authority director Patrick Allen told lawmakers in December. “We’re left with which bad idea satisfies the need.”

Senior U.S. District Judge Michael Mosman brokered a compromise that’s come to be known as “the Mosman order.” Patients charged with violent crimes like Martinez-Romero who would have once been given three years of treatment at the state hospital would now get kicked out after one, thereby making more room for people on the waitlist.

Critics say the policy ignores reality.

“[The] recommendations assumed the existence of a functioning mental health system with adequate capacity, which Oregon has not had for years,” wrote attorneys for the community hospital systems in response to Mosman’s order.

Prosecutors agreed. “It’s like squeezing a balloon,” Barton, the Washington County DA, told WW. “The hospital has been squeezed, and it’s popping out at our end. But there’s nowhere to put these people.”

Barton, along with DAs in Lane and Marion counties, has spoken out forcefully against the early release of patients from Oregon State Hospital. It’s a tricky position in a state dominated by progressive politicians who support deinstitutionalization and alternatives to incarceration.

A Jesuit High School grad who rowed for Gonzaga University, Barton went on to a career prosecuting violent crimes in Washington County before taking over as district attorney in 2018.

While many Oregon DAs’ offices are moving left, Barton has twice beaten well-funded progressive challengers and is now leading the fight against simply discharging state hospital patients to solve overcrowding.

Renaud, the mental health advocate, says he disagrees with Barton on many things, but he admires the prosecutor’s willingness to take on a broken system. “He’s super smart and he’s on this problem,” Renaud says.

Barton has suggested creating “restoration to competency” programs in jails, a strategy being employed in dozens of states from California to Georgia.

These mental health treatment programs operate out of specialized units in jails and offer an alternative to shipping inmates to overcrowded state hospitals. Barton tells WW it’s the “least horrible on a list of horrible choices.”

But his own county’s sheriff, Pat Garrett, bristled at the idea.

“The answer is a resounding NO,” he told the county’s presiding circuit judge, Kathleen Proctor, in a December letter, arguing such a program wasn’t feasible—and plainly illegal under state law.

Barton has joined the federal litigation between the state and mental health advocates and the hospital systems, along with two other DAs and five judges, as friends of the court, arguing that Mosman’s order to release patients after one year is only compounding an existing problem. Washington County has so few community treatment centers that the only way to get treatment for people with severe mental illness is to wait for them to commit a crime and then send them back to the state hospital.

The revolving door is simply spinning faster. One man, Piseat Thouen, was sent back to Washington County from the state hospital on Oct. 25 after he’d attacked a woman in her car with a spear. Three days later, the judge ordered Thouen to go to Providence St. Vincent Hospital where doctors quickly determined he didn’t pose an immediate threat and released him back to the street.

In the case of Martinez-Romero, Barton won a different outcome. His team convinced a judge that Martinez-Romero is now competent to stand trial, now set for September 2024. In the meantime, he sits in Washington County Jail.

“I hope he goes to prison. I don’t think he should get off easy,” says Ian Day, who was stabbed twice by Martinez-Romero outside the Murrayhill Planet Fitness. “He killed someone in front of her daughter.”

For advocates, Martinez-Romero’s case demonstrates the flaws in Oregon’s mental health system, which spends so much money on criminal defendants but so little on community services that might have prevented the crimes in the first place.

“We end up looking at the person at the end of the road, at the jail door or in the institution—which is just really tragic,” says Kevin Fitts, executive director of the Oregon Mental Health Consumers Association. “So many of these things could have been averted.”

Barton has won court approval to prosecute Romero-Martinez’s case. He expects many similar rulings. “We’re getting more and more concerning people,” he says, ticking off a list of names, each charged with murder or attempted murder.

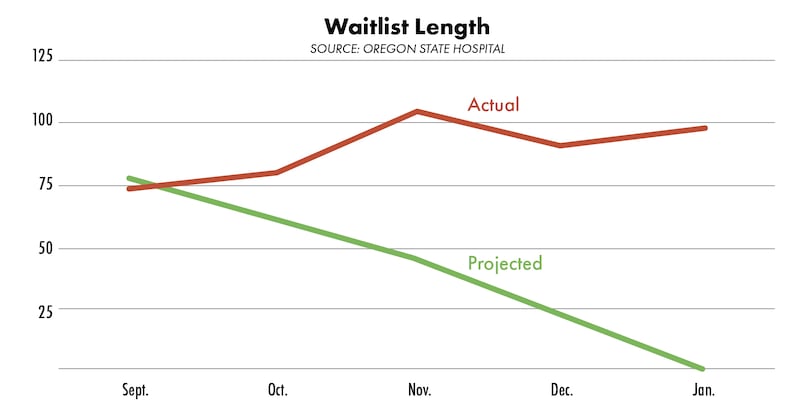

Although the hospital is releasing more patients, the waitlist to get into the hospital isn’t shrinking (see “Waitlist Length,” above).

In September, the state projected 74 aid-and-assist admissions a month until February. In January, there were 101.

Making those defendants wait in jail, where they rarely get effective treatment for their illness, is a constitutional crisis, says legal director Emily Cooper of Disability Rights Oregon. “Jails have been the de facto mental health provider for decades now.”

Some patients are admitted to the state hospital on low-level charges that wouldn’t result in prison time. About 1 in 6 aid-and-assist patients currently at the hospital face only misdemeanor charges. Keeping them locked up at the hospital longer than their presumptive sentences amounts to criminalization of a disability, Cooper argues.

Allen, then the director of the Oregon Health Authority, attempted to reassure lawmakers at a hearing in December. He had one foot out the door—newly elected Gov. Tina Kotek had promised his ouster during her campaign.

Allen alluded to the need for more beds at the state hospital and ran through statistics showing the state was building hundreds of new beds at community facilities, thanks to more than $1 billion in new spending that lawmakers approved last year.

“The system needs more investment,” Allen added. “It probably needs a similar investment to what you just made.”

As for Martinez-Romero, his fate will now be decided by the courts. If convicted, he could be sent to prison—or, if ruled guilty except for insanity, right back to the overflowing state hospital.

“He needs to be institutionalized,” Renaud says. “The question is, just what institution is he going to be in?”