The city of Portland’s Revenue Division estimates a capital gains tax on the May ballot could have sky-high administrative costs, WW has learned.

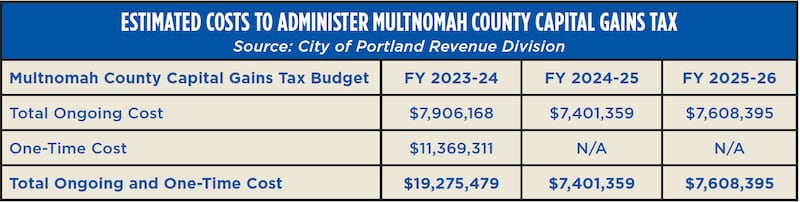

“The tax is expected to raise $12 million to $15 million per tax year,” division director Thomas Lannom wrote in a March 23 memo to county officials, citing a campaign revenue estimate (the city would collect the tax on Multnomah County’s behalf). “The implementation year is estimated to cost approximately $19 million, including startup costs, with ongoing annual costs of approximately $7 million.”

Based on the midpoint of the revenue the Eviction Representation for All campaign hopes to raise—$13.5 million—the costs of administering the tax could consume more than 50% of the revenue.

That’s a lot compared to the Metro supportive housing services measure, which capped administrative costs at 5%, or even the Portland Arts Tax, which over the past decade has cost about 11.5% to administer.

If passed by county voters next month, Measure 26-238 would charge Multnomah County residents a 0.75% tax on long-term capital gains and use the money to provide support and legal representation to tenants facing eviction. (Eviction Representation for All uses the IRS definition of a long-term capital gain: the net profit from the sale of an asset such as a stock, bond, property or business held for more than one year.) If passed, the measure would be the nation’s only local capital gains tax. It would also be retroactive to Jan. 1, 2023, which is different from the last two local, income-based taxes.

The high administrative costs, Lannom explains in his memo, stem from a variety of factors. The tax is new and has a short implementation window; it would generate a lot of filers. “The proposed capital gains tax is required to be paid by all taxpayers with a capital gain and has no lower income threshold,” Lannom tells WW. “This means tens of thousands of taxpayers who are not currently required to file a personal income tax return for Metro or Multnomah County and potentially even the state of Oregon will be required to file this return.”

Lannom projects that because of one-time startup costs of $11.4 million (in addition to operating costs of $7.9 million), the measure is likely to cost $19.3 million in its first year—far more than it’s expected to raise.

Lannom, whose agency also collects income taxes for Metro and Multnomah County, concedes that his cost estimates could be high. “It is possible that the expenses could come in substantially below budget if the risk-related contingencies are not utilized,” he writes.

Colleen Carroll of the Eviction Representation for All campaign says Lannom’s memo includes some encouraging news: It estimates only about 8% of county residents would have to pay the tax. “As we have always maintained, this tax targets a small and wealthy portion of the population to pay for a proven homelessness prevention and housing stability solution,” Carroll says.

She adds that even if Lannom’s calculations are correct, the cost of the measure would be far less than the overall cost of evictions in Multnomah County, which the campaign pegs at $83 million. “The analysis from the city,” she says, “reflects a worst-case scenario for the most expensive of the available options.”

County Commissioner Lori Stegmann says the high cost of collecting the tax should give voters pause.

“As a small-business owner and representative of east county, I know we need to use every dollar wisely,” Stegmann says. “And this measure misses the mark.”