Three thousand five hundred dollars.

That’s how much it’s going to cost to swallow 4 grams of psilocybin mushrooms and undergo a six-hour therapy session at EPIC Healing Eugene—if and when the clinic gets its license to run a “psilocybin service center” and its owner, Cathy Jonas, gets her facilitator license after undergoing 300 hours of training and passing a state-mandated test.

Together, those two licenses will cost her $12,000 a year. On top of that, she must spend thousands on a security system, liability insurance, and a 375-pound safe. All in, Jonas estimates she’ll spend $60,000 to open her service center and, at $3,500 a session, she expects to barely break even. “They have really made this hard,” Jonas, 56, says.

Two and a half years ago, Oregon voters approved Measure 109, making Oregon the first state in the nation to legalize the supervised use of psilocybin mushrooms. But that freedom comes with fine print. The program requires users to trip only in the presence of a trained facilitator in a service center using psilocybin grown by state-approved manufacturers and tested by state-licensed labs.

All of that adds costs. The result is a price tag that’s going to astonish the fungi-curious. A single session—5 grams, six hours—will cost more than the median Oregonian’s biweekly take-home pay.

Still willing to pony up? Sorry, get in line. At press time, no service centers—the only places you’re allowed to take psilocybin legally—had been licensed by the Oregon Health Authority. Three manufacturers, one testing lab, and just four facilitators had been licensed as of April 25.

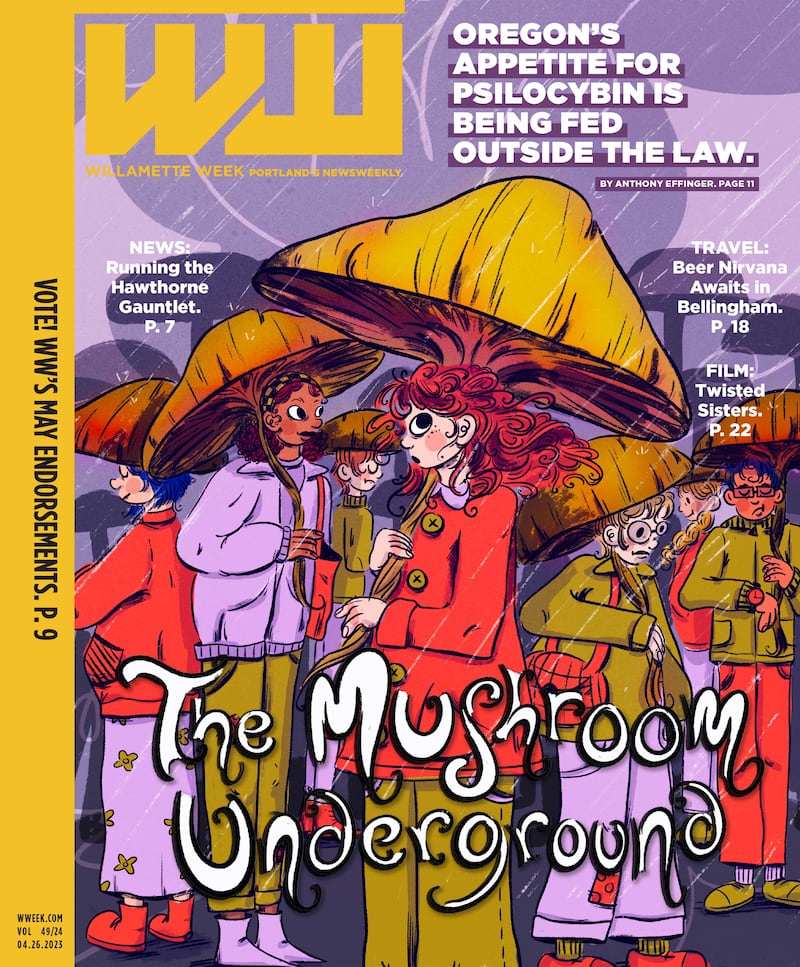

In other words, the ballot measure created an appetite that the regulated system seems unprepared to satisfy. The outcome? The legalization of psilocybin mushrooms in Oregon is spurring an expansion of the decades-old illegal market.

“There are people and organizations openly facilitating psilocybin trips outside of the state-run system in Oregon,” says Vince Sliwoski, a lawyer at Harris Bricken Sliwoski LLP who specializes in cannabis and now psilocybin. “You don’t have to look that hard to find them. There’s going to be a big underground economy for this stuff.”

That underground is already expanding, people in the industry say. Facilitators, some of them newly graduated from trip training programs, are leading sessions in their homes, in Airbnbs, and on psychedelic retreats abroad. Amateur mycologists are growing hundreds of grams of Psilocybe cubensis in plastic tubs in basements around town.

A shaman named James Hin has opened the PSILO Temple, a church in Eugene, where psilocybin is the sacrament for the dozens of congregants who come to Hin’s “Wisdom Wednesday” services twice a month.

The former accounting executive says his church is protected by both the First Amendment and the Religious Freedoms Restoration Act of 1993, passed by Congress after the Supreme Court upheld a move by the Oregon Department of Human Resources to deny unemployment benefits to two Native Americans who were fired from drug counseling jobs because they had tested positive for peyote, which they had taken during a religious ceremony.

“I’ll defend these protections all day,” Hin says. “I’m not some hippie in a van.”

To be sure, much of the underground activity predates Measure 109. Mushrooms grow like, well, mushrooms, in the Northwest, and Ken Kesey, one of the leaders who alerted the white, Western world to the power of psychedelics in the 1960s, is the son of Oregon soil.

Nate Howard, co-founder of InnerTrek, a facilitator training program, says the legal regime is a product of the underground, not the other way around.

“The underground has been thriving from the start,” Howard says. “That’s what made it possible for Measure 109 backers to collect enough signatures to pass it.”

But the mushroom economy went into hyperdrive after Measure 109 passed, along with Measure 110, which decriminalized possession of shrooms and most other illicit drugs.

For proof, recall the five-hour lines at Shroom House, the much-loved, illegal and short-lived psilocybin outlet on West Burnside Street that the cops shut down in December (“Mushroom Pop-Up,” WW, Dec. 6, 2022).

Or visit High Desert Spores off Northeast Fremont Street, where Don and his wife, Kay, the owners, sell hundreds of pounds of rye berries and sorghum, preferred growth media for mushrooms of all kinds so that people all over Oregon can grow their own.

Even those who have embraced Oregon’s legal shroom system question its merits. Naturopathic physician Erica Zelfand is one of four lead educators at InnerTrek, the first facilitator training program to disgorge graduates into the world, last March. She took the course at the same time.

“What’s the incentive for somebody to actually want to do this work above ground when they can go underground and make it much more accessible?” Zelfand asks.

WW set out last month to explore the shroom underground, talking to trip guides, growers, religious leaders, and peddlers of shroom-growing supplies (and swallowing tincture sacraments). None had remorse about working around the rules because, for them, psychedelic mushrooms are too promising for mental health (and even world peace) to leave only to the wealthy who can afford state-sponsored trips.

We’re not trying to get anybody busted. Unlike the balls-out proprietors of Shroom House, the people running underground sessions are disguising their activity or finding legal shields, and we’ve respected that, with varying degrees of anonymity.

Here’s a look at what’s beyond the state’s purview.

The Facilitators

Originally from Dallas, Bryce, 38, had been meditating for most of his life when he took a small, 1.5-gram dose of mushrooms at the Oregon Coast about five years ago.

“All of a sudden, I had this experience of my body and the universe dissolving into the same continuum of consciousness,” Bryce says. “It sounds cliché, but the light just came on.”

Bryce, already a licensed clinical social worker, was among the first class of graduates last month from one of the state-approved psilocybin facilitator courses required to work (someday) in a psilocybin service center.

The training lasted six months and cost him $7,900. Now, Bryce is licensed to work in clinics that don’t yet exist, and might not for months. So, last fall, he added psilocybin sessions to his counseling options, without a license.

He gets his clients through Google, where he advertises psychedelic services, and through word of mouth. He agreed to talk to WW on the condition we give him a pseudonym because, by operating outside of Measure 109′s rules, he risks violating state drug laws.

“Any activity in the unregulated space is subject to criminal penalties, which is a matter for law enforcement,” Angela Allbee, manager of OHA’s Psilocybin Services Section, said in an email.

Bryce, who has little tolerance for the New Age tropes that often accompany psychedelics, goes to clients’ homes. If they come from out of town, he goes to their Airbnbs. He charges $200 per 50-minute session for a multistep program that begins with five preparatory sessions, culminates in a trip, and ends with an integration session in which trippers aim to apply the awareness gained during the psychedelic journey into their daily life.

The lengthy prep is necessary, Bryce says, because he recommends 8 grams of mushrooms for trips, a higher dose than most. Oregon Psilocybin Services allows a maximum of 50 milligrams of psilocybin, the amount found in about 5 grams of dried mushrooms, another problem with the program.

“When people take these high doses, they start to feel like they’re dissolving into everything,” Bryce says. “If people aren’t ready for that, it can be really overwhelming. I do a series of meditations that simulate that effect for people when they’re sober.”

All in, tripping with Bryce costs $3,200, but it includes many more hours of prep per trip. He offers a 25% discount for people of color.

Bryce is one of many people leading psychedelic trips in Oregon’s residential neighborhoods. June (also a pseudonym) has been guiding people on trips for six years.

A jill of all trades who has worked in film, publishing and consumer-product development, she has no pretenses about being a shaman or even a therapist. She refers to her practice as “holding space” for people so they can trip safely and extract as much from the experience as possible through preparation before, and integration after.

June, 50, holds space for just two clients a week, which is a full schedule, she says. Trips last for hours, and they can be intense. She charges between $800 and $1,500, based on need.

She got into the practice after a single mushroom trip lifted her own stubborn case of depression. Friends heard about it and wanted the same, so she began sitting with them during trips. People liked her style and, through word of mouth, she built a practice. Most of her clients are dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder and complex trauma from childhood.

Unlike Bryce and many other underground facilitators, June never considered taking a training program, because it felt like a “slap in the face” to people who have been leading clients on trips for years, including Indigenous people whose forebears have been at it for centuries. Now the programs’ graduates are hitting the street after just six months.

“My hunch is that the underground is going to get completely flooded with trained facilitators who aren’t any more credentialed or licensed than me,” June says. “I don’t see these people getting super excited about working with psychedelic medicine and then not doing it just because they can’t work out of a registered service center.”

Indeed, a company called Psychedelic Passage “curates a network of U.S.-based psychedelic guides and trip sitters who facilitate in-person ceremonial psychedelic experiences with an emphasis on harm reduction,” according to its website. Psychedelic Passage offers guides in all of Oregon’s major cities (and even smaller ones like Albany, Tualatin and West Linn).

The company, with a co-founder in Bend, appears to skirt the rules by requiring that you BYOS (bring your own shrooms).

The Retreat Leader

Type “psilocybin retreat” into Google and dozens of options pop up, including many in Jamaica, where psilocybin has always been legal. The Caribbean nation is trying to create a tourism business out of tripping. A company called MycoMeditations has four retreat sites there, including a super-luxe one at Bluefields Bay that starts at $13,100 per person.

Among the people who have led retreats in Jamaica is an Oregonian: naturopathic physician Erica Zelfand.

On her website, Zelfand calls herself “a fiery empath and the most extroverted introvert I know.” She’s in another country now, and asked us not to name it. Reached by Zoom, she stood in front of a yard full of tropical greenery, which, combined with her sunny demeanor, took the edge off Oregon’s cold, drenched April.

Zelfand just graduated from InnerTrek in March, getting her certificate while she taught courses there. She says Oregon’s psilocybin program is a good start, but she doesn’t expect to practice in-state anytime soon.

“Rome wasn’t built in a day,” Zelfand says. “The Oregon model is a little too careful in my personal opinion. But it’s always better to start rigid and then loosen over time.”

Zelfand agrees with Bryce that one of the biggest problems in Oregon is the “hilariously low” maximum dose, 5 grams. Considered a “hero dose” for most people, where their egos melt into the universe like butter, 5 grams may not be enough for someone on antidepressants. Drugs like Lexapro act on the same neurotransmitter—serotonin—as psilocin, a metabolite of psilocybin.

“The last person I worked with who was on an antidepressant needed 12 grams,” Zelfand says.

For that and other reasons, Zelfand is living abroad and inviting people to psilocybin retreats there. Her six-day programs cost $3,333 and include accommodation, meals and snacks. She also offers massages, yoga, guided meditation, “shadow work,” and space in a sweat lodge.

Also, the weather is better.

The Mycology Supplier

Walk into High Desert Spores just off Northeast Fremont Street and you’d think it’s little more than a gardening boutique, albeit one with oddities like “pasteurized substrates” and “sterilized grains.”

A display wheel at the counter has dirty Q-tips in sealed envelopes with names like Hillbilly Pumpkin, Leucistic Golden Teacher and Jedi Mind Fuck. Get closer and you see that the dirt stains are actually bluish spores from the genus Psilocybe and the species cubensis (the American mycologist who described them found his first specimens in Cuba in 1906).

Put them in a dark warm place, add some love, and they’ll grow into magic mushrooms. One envelope of Jedi Mind Fuck spores costs $25.

The spores and materials used to grow psychedelic mushrooms contain no psilocybin. Even so, they fall into a legal gray zone because U.S. law makes it illegal to sell any “equipment, product or material” that is “primarily intended” to make a controlled substance.

Don, 47, the tall, jovial owner with a trimmed beard and royal blue polo shirt emblazoned with his corporate logo, says he’s on the right side of the law.

“If we were a pizza restaurant, we would be Papa Johns,” says Don, who didn’t want his last name in print. “I’d give you all the ingredients to take it home and bake it yourself. But I’m not going to give you the finished product. I’m not going to give you the cooked pizza.”

To get a sense of the demand from DIY mushroom growers in Portland, ask Don to take you through a curtain to the back of the store. There, he has installed a 10-foot-long autoclave that has a circular hatch like a torpedo tube. He’s working to get it running and, in the meantime, uses a row of smaller machines.

Autoclaves are industrial-strength pressure cookers (think Instant Pots) that use high pressure and temperature to kill bacteria and viruses. Unlike making pizza, almost everything involved in growing mushrooms must be sterilized to near-operating room levels because other life forms will outcompete them in the nutrient-rich environments they prefer.

Don moved to his new location near Fremont from Milwaukie because he needed more space to meet demand. (Before that, he was in Bend. Hence, the High Desert name.)

Don packs his autoclaves with substrates and grains—everything his customers need to grow mushrooms of all kinds, not just psychedelic ones. Don glows when he talks about lion’s mane, cordyceps and turkey tail. Like many in the mushroom economy, he’s more coy about psilocybin.

“There is so much trauma, anxiety and depression in this world right now,” he says. “And people are sick and tired of pharmaceutical drugs. Our hospital system is nothing more than a glorified drug dealer pushing super-expensive things. I’m not saying that mushrooms are the cure, but they are a great tool to have in the toolbox, and if you’re willing to explore it, then you should have access, and it shouldn’t cost you $3,000 or $4,000.”

The Shaman

In the Catholic Church, the sacrament comes near the end, in the form of a wafer and wine transubstantiated into the body and blood of Christ. At the PSILO Temple in Eugene, the sacrament comes at the beginning, in the form of psilocybin dissolved in vodka.

At a Wednesday service this month, James Hin called congregants (who had signed waivers) to receive two squirts of the tincture from a dropper. He offered a chunk of psilocybin chocolate to those who wanted to go a little deeper.

Not all participants went up for the sacrament, but everyone listened to a sermon by Hin. In it, he urged people to join the PSILO Temple (it’s pronounced “sillo temple,” and each letter stands for one of Hin’s values; O is for “oneness”). Membership costs just $44 a year. He also described “stoned ape theory,” which holds that early hominids discovered psychoactive mushrooms and they supercharged human evolution.

After he finished, the group of about 60 unrolled yoga mats and lay down to listen to Hin and a musician named Yiyetta Love play singing bowls, strike gongs and sing, creating a “sound bath.”

Hin, 37, says he discovered he was a shaman in his late 20s, when he experienced “shaman sickness.”

“It’s when you have a calling but you don’t use it,” he says.

Hin, who is clean-cut and built like an athlete, has a pretty nonmystical background for a shroom shaman. Originally from Morris County, N.J., he has a master’s degree in organizational and social psychology from the London School of Economics. He worked for years as an organizational development manager, first at a company that made sprinkler systems and then at an accounting firm, both near San Diego.

In the midst of deep depression in 2017, Hin went online to find out how to kill himself and make it look like an accident so his kids wouldn’t know. He found an ayahuasca documentary instead. He tried the drug. “Ayahuasca saved my life,” Hin says. “It didn’t heal everything, but it gave me hope to keep exploring life.”

Later on, he set up a psilocybin trip, and on the way there he stopped at a Guitar Center store and bought a singing bowl, a Tibetan instrument that’s become popular in the West. About 90 minutes into the trip, Hin struck the bowl with a mallet and his life changed. He saw sound waves in the air, and he started chanting.

“I had no idea where the chants came from,” he says. “The sound bowl disappeared out of my hands. And then it came back, and it felt like it came from a thousand years away.”

Hin did the logical thing after that: He moved to Eugene, where mushrooms and other plant medicines are as common as bratwursts in Chicago. He planned to stay in accounting, but he decided to found the PSILO Temple instead.

Hin says he operates openly and makes psilocybin available at almost no cost because the world needs the compound to survive. “I feel like I was sent here from the universe to do this,” he says.

Sam Chapman, campaign manager for Measure 109, says psychedelic therapy is evolving, and early adopters in the state’s legal system are taking some risk.

“With any bootstrapping startup business, there’s going to be a failure rate,” Chapman says. “This is a serious endeavor, and we want people to have their eyes wide open. Sometimes that requires a little dunk in the cold plunge. Long term, that’s shown to be healthy.”

Depending on their expectations, many graduates of Oregon’s training programs are getting dunked right now. They stumped up thousands for training and having no place to practice.

Iconoclasts like Hin don’t think it has to be that way. It would be ironic if a former accounting executive from California pushed Oregon into a more inclusive, less costly, less bureaucratic regime for state-sponsored tripping. But, right now, James Hin seems as likely a savior as Chapman, or anyone else.