Gamblers across America wagered $6.4 billion on horses and greyhounds last year thanks to the state of Oregon.

It’s more than half of the total amount bet legally on horse and dog racing in the U.S., whether at tracks, at off-track betting parlors or online.

Oregon’s supremacy in the realm of accepting bets on animals—whether the gamblers are in Alaska or New York and whether the dogs or ponies are racing in California or New Zealand—is remarkable for two reasons.

First, there is almost no animal racing left in the Beaver State. The last dog track, Multnomah Greyhound Park, closed in 2004. Oregon’s last major horse track, Portland Meadows, closed in 2019, replaced by a Legoland of Amazon warehouses.

“It’s unusual that a state that has such a small thumbprint in racing is so important to an overall industry,” says Patrick Cummings of the Thoroughbred Idea Foundation, a horse racing industry think tank in Lexington, Ky.

Second, the Oregon Racing Commission, the little-known state agency that presides over this near monopoly, makes almost nothing from it—and far less than it could.

The Racing Commission does so in service of an industry widely criticized for its cruelty to animals (see “Giving Us Paws,” page 16), a concern highlighted by seven equine deaths at Churchill Downs on the eve of the Kentucky Derby earlier this month.

Kitty Martz, executive director of the group Voices of Problem Gambling Recovery, says Oregon provides unhealthy temptations for bettors across the country by making it easy for them to bet on dogs and horses anywhere, anytime.

“My main concern is that when it becomes hand-held digital, research shows the potential for gambling addiction goes way up,” Martz says. To make matters worse, she adds, Oregon facilitates billions of dollars in betting for a pittance: “We [Oregonians] are not benefiting.”

It’s a busy time for the Racing Commission: Two legislative committees have taken an unusual level of interest in it—and the Secretary of State’s Office will soon release an audit. For the past two months, WW has examined hundreds of pages of emails and other documents, and interviewed lawmakers, animal rights advocates, and gambling experts.

What emerges is a picture of an agency shrouded in obscurity, often unaccountable, largely ignored by the Legislature and governor’s office, and apparently in thrall to the industry it regulates. The reasons appear to have less to do with corruption than inattention; out-of-state vice merchants have simply identified Oregon as the nation’s easiest mark.

To say the Oregon Racing Commission is an afterthought in the state’s bureaucracy would be like saying Jeff Bezos sells a few things online.

The commission’s 15 employees don’t even have an office.

The second and, by law, final term of the Racing Commission’s current chairman, Charles Williamson, ended nearly eight years ago, on Sept. 17, 2015. Yet he remains in charge of the five-member volunteer board appointed by the governor.

“Why am I still on the commission?” asks Williamson, 79, a Portland lawyer. “I’m not sure. I had two four-year terms, and they never appointed anybody to replace me.” Another commissioner has served four years past her term’s expiration date, and one of five seats on the board recently sat empty for nearly a year.

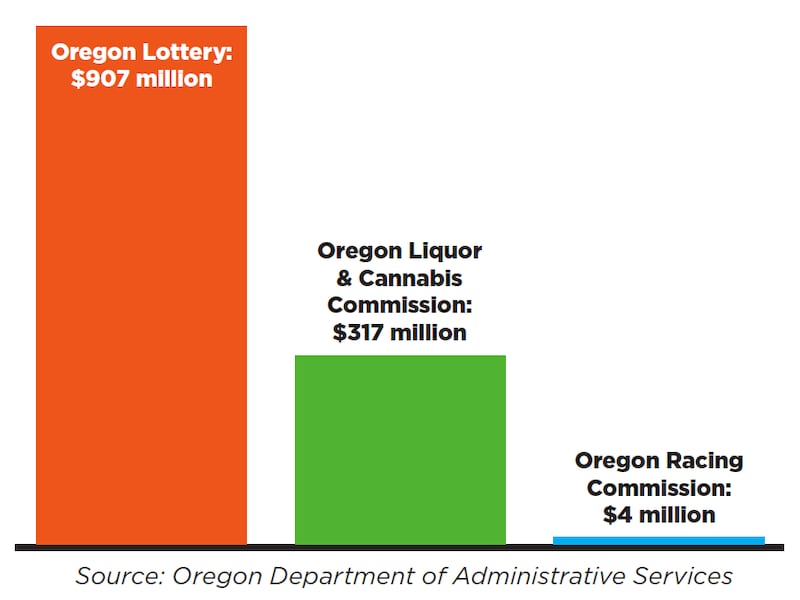

The Racing Commission, like the Oregon Lottery and the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission, is what’s called an “other funded” agency. Rather than relying on tax dollars for their budgets, such agencies generate cash for the state by working with private industry to sell something: booze, weed or the thrill of gambling.

Compared with the lottery and the OLCC, which generate huge amounts of revenue for the state, the Racing Commission raises almost nothing (see graphs below).

“The Oregon Racing Commission is effectively an extension of the gambling industry,” says Les Bernal, national director of Stop Predatory Gambling. “It’s a con driven by greed, and it doesn’t serve the public’s interest.”

Oregon became the epicenter of remote gambling—what is formally called advance-deposit wagering, or ADW—almost by accident.

During the 1999 legislative session, Dave Nelson, then a lobbyist for Portland Meadows, and the late Mike Dewey, who represented the Multnomah Kennel Club, proposed a moonshot. Both sports were in decline because of the creation of the Oregon Lottery in 1984, the advent of video poker in 1991, and the tribal casinos that soon followed.

“We were trying to preserve racing,” Nelson recalls. “It was a last-ditch effort to provide some extra revenue for the tracks.”

Nelson proposed an adaptation of online shopping that would allow gamblers from anywhere in the country to bet on dog and horse racing anywhere in the world from their computers.

When people bet on horses or dogs, all their money goes into a parimutuel pool and they bet against each other, rather than betting against “the house” as they do in casinos. By agreeing to serve as the legal host for that pool, Oregon would offer a service no other state was willing to provide.

Taking bets from all over the country and booking them in one state required a legal leap of faith. Oregon lawmakers, unlike those in other states, decided to take the risk. It gave Oregon a first-mover advantage it has never lost.

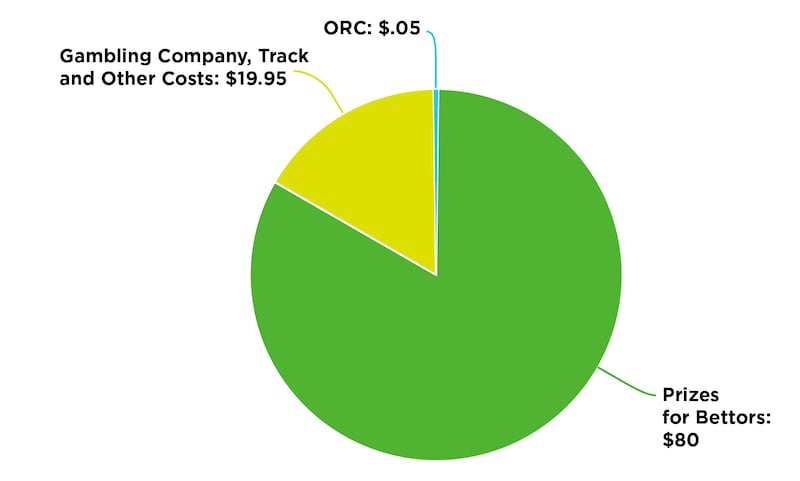

In essence, the state of Oregon was joining a syndicate with racetracks like Churchill Downs and would earn a tiny piece of the action, which today equates to about 0.05% of the total amount bet—in industry parlance, the handle.

Lawmakers approved ADW betting in 1999, unsure if anybody would care. In terms of saving the tracks, it failed. But in terms of attracting gamblers, it succeeded beyond anybody’s wildest dreams, generating billions of dollars in ADW bets even as the number of bettors at horse and dog tracks continues a long-term decline across the country.

“Today, Oregon’s tracks are long gone and this ADW betting is stronger than ever,” says Nelson, who is retired from lobbying but still active in Oregon horse racing issues.

Now, gamblers can use their mobile devices to bet on horses and dogs around the globe—and, more likely than not, those bets get booked in Oregon through one of nine ADW betting hubs arrayed around the metro area.

Oregon now books about 95% of all ADW bets placed nationally—more than all the bettors wagered in person at all the horse tracks in the country last year.

“There is a question of why Oregon’s dominance has continued to persist,” says Cummings of the Thoroughbred Idea Foundation. “It feels like kind of a choke point that so much of the business is focused on a single state.”

Nobody in the U.S. has done more to curtail greyhound racing than Carey Theil, the executive director of Boston-based Grey2K USA. And it is Theil’s work in Salem over the past two years that has focused lawmakers, such as state Reps. John Lively (D-Springfield) and David Gomberg (D-Otis), on ADW betting and the Racing Commission.

Over the past two decades, Theil and his organization have led the passage of 18 anti-greyhound racing laws across the country, leading to the closure of 46 tracks. West Virginia is now the only state in the U.S. that still hosts dog racing—and Theil hopes to put an end to that.

Theil, 45, grew up in Southeast Portland in a family scarred by addiction. An indifferent student, he focused his energy on other interests: the Trail Blazers, chess (he plays at the master level), and the politics of animal rights. He got his start working on a 1994 ballot measure that banned the use of dogs for hunting bears and cougars. That hooked him.

In 1997, Theil bought a suit at Goodwill, boarded a Greyhound bus from Portland to the state Capitol, and began testifying on any bill that involved animals or animal rights.

Like Nelson, the Portland Meadows lobbyist, Theil was there at the beginning of ADW betting in Oregon.

“My mother and I were the only opponents of that legislation,” Theil recalls. “I didn’t know what I was doing then, but I testified against it.”

Theil relocated to Boston in 2001 to work on greyhound racing bans in Eastern states, but continued to press Oregon lawmakers about the Multnomah Greyhound Park. In 2004, four years after a trainer’s neglect led to the deaths of six greyhounds in transit from Wood Village to Florida, the park, already suffering from low attendance, closed.

“The Multnomah track was the jewel in the crown of American greyhound racing,” Theil says. “I think its closure was particularly demoralizing for the industry.”

But like a gardener who chops back a blackberry bush only to discover a vast underground root system, Theil watched with dismay as ADW betting exploded. Greyhound racing is all but extinct in the U.S., but still thrives overseas—thanks in part to Oregon.

Theil and other critics would like Oregon to get out of the business of betting on animals. Even though Oregon has a near monopoly in horse and dog betting, it takes in less than $4 million a year in revenue, while facilitating more than $6.4 billion in bets.

Three-quarters of revenues go to sponsor horse racing at rural county fairs around the state—in Tillamook, Crook and Union counties. And a little goes to Grants Pass Downs, the state’s one remaining commercial horse track. The balance, less than $1 million a year, goes to the state general fund.

Part of why the business is such a dud: a decision long ago to cap the taxes the Racing Commission collects from gambling companies. Oregon charges the companies a licensing fee of $73,000 plus a percentage of the total amount bet (0.125% for the first $60 million, then 0.25% up to a cap of about $800,000 in total payments).

Williamson, the Racing Commission chair, says the decision to cap taxes predated his joining the panel in 2008. In 2016, the commission reduced the annual rate at which the caps can increase from 7.5% to 2.5%. “We were trying to incentivize companies to stay,” Williamson says.

But ADW betting volumes skyrocketed during the pandemic (see chart below), making the cap on taxes a total giveaway to big gambling interests.

Without the cap, the Racing Commission would have taken in nearly $16 million in taxes last year, instead of less than $4 million.

It’s a puzzling scheme, like telling Warren Buffett and Elon Musk they must pay tax on the first few million dollars of their income, but everything above that is tax free.

The system is working well for out-of-state gambling companies, such as Kentucky-based TwinSpires, which is owned and operated by publicly traded Churchill Downs Inc. Best known for running the Kentucky Derby, Churchill Downs also operates racetracks and casinos in 11 states.

A March investor presentation shows that its ADW betting business, booked through TwinSpires’ Oregon office, grew more than 40% during the pandemic and generated pretax profits last year of $115 million. (Representatives of the company did not respond to requests for comment.)

Theil, the greyhound protection advocate, says it adds insult to injury that Oregon is abetting the mistreatment of animals and gambling addiction for almost no benefit: “The fact that the state is receiving virtually no revenue from [ADW] is outrageous.”

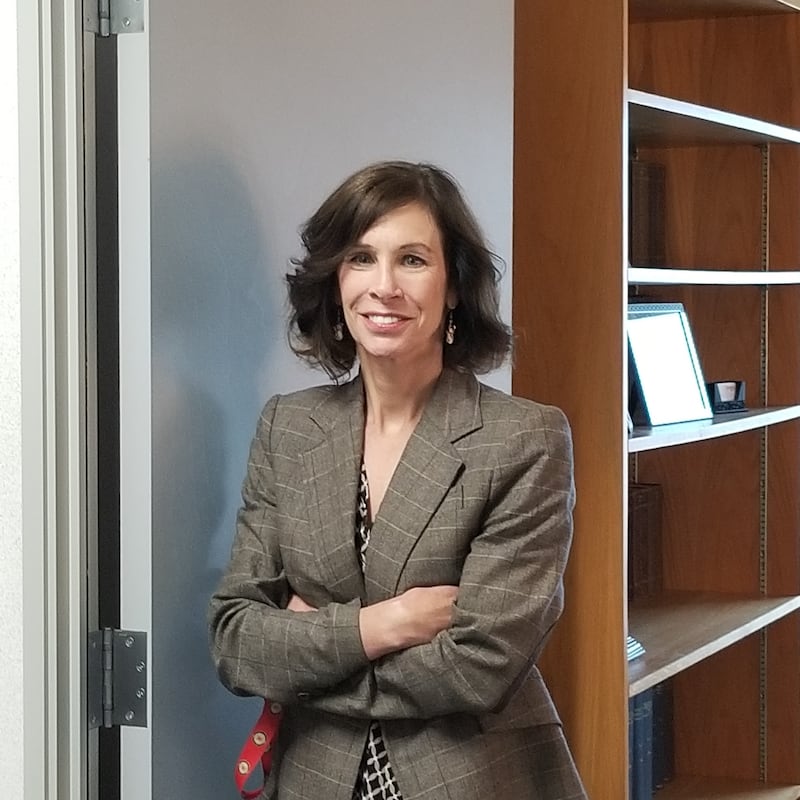

The person watching over these deals? Connie “Pepper” Winn, executive director of the Oregon Racing Commission.

A former U.S. Army recruiter who worked in banking and for-profit education, Winn, 60, came to the Racing Commission in 2014 and first took the job of “director of mutuels,” a post that took her all over the country and as far afield as Sri Lanka to visit and audit the companies booking bets through Oregon (the gambling companies reimbursed her travel costs).

When she applied for the agency’s top job last year, she noted an affinity for its work. “As a youth, I was an equestrian and bought my first horse, who was a retired racehorse,” Winn wrote in her cover letter. “He was a direct decedent [sic] of Man o’ War—one of my all time favorites.”

Theil says Winn regards her job as doing the industry’s bidding. “Connie Winn is a quintessential example of what it looks like for a regulator to be captured by the industry she’s supposed to be regulating,” he says.

Winn disagrees with that characterization. She says she and her agency have diligently audited the gambling providers and always look out for the public’s interest.

“I work for the citizens of Oregon,” Winn says.

In emails and legislative testimony this year and last, both her predecessor, Jack McGrail, and Winn have repeatedly warned that any attempt to change the terms of ADW betting companies’ current arrangement would send them fleeing to other states.

“They’ll leave,” Winn told lawmakers earlier this session.

Despite her usual unfailing courtesy, Winn has not always cooperated with the Legislature, which sets her agency’s budget. After the passage of Senate Bill 1504 in 2022 to limit betting on dogs, she stonewalled a request by state Rep. Gomberg, one of the bill’s sponsors, for information about compliance with the new law.

That led to a remarkable moment in February when Winn refused to answer Gomberg’s questions about the dog racing bill in a public hearing.

“I’ve been advised not to comment,” Winn, whose annual salary is $143,952, told Gomberg, who co-chairs the Joint Ways and Means Subcommittee on Transportation and Economic Development. That panel oversees the Racing Commission budget. She cited guidance from the Oregon Department of Justice, which advises the agency.

That refusal echoed around the Capitol. State Rep. Paul Evans (D-Monmouth) says he was “stunned” by Winn’s stance.

“Anybody who decides to take the Fifth or give a squirrely answer like that, it’s a bad sign,” Evans says. “There should be an investigation into what’s behind that.”

This session, Winn has appeared in front of both Ways and Means and the House Committee on Gambling Regulation.

In hearings, it quickly became clear that lawmakers had little understanding of what the Racing Commission does or of Oregon’s puzzlingly dominant position in the realm of betting on animals.

“Why do we do this?” Lively asked Winn at a March 14 hearing.

“It’s extremely complicated and hard to get your head around,” Winn told the committee. “But we are basically getting free money.”

In 2022, when Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem) and Rep. Gomberg sought to crack down on dog betting with SB 1504, which prohibited Oregon from taking greyhound bets from people living in states where such wagers are illegal, the gambling industry pushed back.

“Senate Bill 1504, if passed, will adversely affect almost every Oregon ADW and will definitely cause many, if not all, of the affected ADWs to exit Oregon and find a new business jurisdiction to avoid a significant loss of revenue from their businesses as currently operated,” testified Shawn Miller, a lobbyist for TwinSpires. “The passage of SB 1504 will also likely decimate the Oregon Racing Commission and cast doubt on the viability of the entire racing industry in Oregon.”

The Senate bill passed. None of the ADWs left Oregon over it, although Winn now says U.S. Off-Track, one of the smallest providers, is leaving.

Sharon Harmon, longtime director of the Oregon Humane Society, says it’s time Oregon reconciled its reputation as a state with the strongest legal protections for animals who live here with its role as the leading facilitator of betting on animals worldwide.

“It’s ironic that we are promoting an industry built on cruelty,” Harmon says. “That doesn’t seem to match the values of our citizenry.”

Gov. Tina Kotek also says it’s time for a serious look at the commission’s work.

“Gov. Kotek has concerns about the oversight and accountability of the Racing Commission and has directed staff to evaluate options for potential reforms,” says Kotek spokeswoman Anca Matica.

Theil is determined to stop Oregon from continuing to take greyhound bets from people in states that ban racing. “All these fights come back to Oregon in the end,” he says.

And after questioning Racing Commission director Winn about why her agency serves as a national betting hub, the chair of the House Committee on Gambling Regulation came to a similar conclusion.

“I don’t see why we are still doing this in the state of Oregon,” Lively says. “There doesn’t seem to be a justification. But we get hooked on revenue in this state. And once we are hooked, it’s very hard to get off.”

Giving Us Paws

Critics say animal racing is wicked in two ways.

There are two kinds of critics of the business of betting on animals. The first are animal rights activists, such as Carey Theil of the anti-greyhound racing group Grey2K USA, who say the racing industry treats animals inhumanely: overbreeding greyhounds, for instance, keeping them trapped in cages for most of their racing lives, drugging them to go faster (or, sometimes, slower), and dumping them, sometimes in mass graves, when their racing days are done.

Horse racing critics find the sport of kings equally immoral. The persistently high rate of overbreeding, doping, racing-related deaths, and other abuses prompted Congress to pass the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act of 2020.

That law didn’t change much, as evidenced by the deaths of seven horses in the days leading up to the most celebrated horse race in the nation: the May 7 Kentucky Derby, held at Churchill Downs in Louisville.

“Churchill Downs is a killing field,” People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals said in a statement after the seventh death. “They should play taps at the derby instead of ‘My Old Kentucky Home.’”

Investigations by advocacy groups such as PETA and years of reporting by The New York Times have shown unscrupulous horse trainers employ more chemicals than meth cooks, often leading to injury and death as drugged animals exceed their natural capacity for exertion.

Animal racing in Oregon has long generated strong opposition from powerful opponents such as former Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem), who introduced a bill in 2021 that would have banned horse racing entirely in Oregon (the bill failed).

In 2022, Courtney and state Rep. David Gomberg (D-Otis) co-sponsored Senate Bill 1504, which curtailed betting on dogs. “I think Oregonians would be disgusted by the abuse these dogs experience,” Courtney told his colleagues then. “Oregon should not be promoting or engaging in this abuse at any level.”

Courtney tells WW that if it were up to him, Oregon would outlaw all forms of animal racing and would play no role in betting on either sport. He regrets leaving that work undone. “I wish I could have stuck around to end horse racing in Oregon,” he says.

The second kind of critics are anti-gambling activists, who say Oregon looks at only the revenue side of gambling, while ignoring the legal, financial and social costs of problem gambling.

Kitty Martz, executive director of Voices of Problem Gambling Recovery, says Oregon would be better off if it tightened regulations instead of chasing every possible gambling dollar.

Martz has long faulted the state for ignoring the cost of gambling addiction, even as the Oregon Lottery grows by leaps and bounds and betting on animals explodes.

“Gambling in Oregon is this nonregulated sprawl,” she says, “and it’s become a race to the bottom.”

Playing the Field

The Oregon Racing Commission keeps looking for ways to please the industry.

In two recent instances WW examined, the Oregon Racing Commission moved unilaterally to expand gambling, only to be blocked by state officials once they learned about the plans.

In 2021, the commission granted a company called Luckii.com a license—which it would need in order to offer mobile betting on “historical horse races,” which simulate racing using historical data but produce different outcomes than the original races. But legal experts in multiple states have determined they are basically video slot machines, which Oregon does not allow.

Emails WW obtained under a public records request show that license approval for Luckii.com shocked officials at the Oregon Lottery, the Oregon Department of Justice, the Oregon State Police, and the Siletz and Grand Ronde tribes.

The reason: The Racing Commission’s decision gave Luckii.com permission to in essence run slot machines on mobile phones, a practice forbidden to the Oregon Lottery and the state’s tribes.

“It’s unclear to Grand Ronde how this type of gaming is legal in Oregon and how such online gaming is regulated,” Rob Green, a lawyer representing the Grand Ronde, wrote to Gov. Kate Brown’s office on Feb. 25, 2021. “The Tribe is very concerned about the continued expansion of gaming in Oregon without any notice or input from Oregon tribes.”

State Rep. Paul Evans (D-Monmouth) was among the lawmakers who reacted with fury when they discovered the Racing Commission had greenlighted Luckii.com’s application.

Evans fired off an angry email to then-Racing Commission director Jack McGrail. “At no time in the discussions, NO TIME, was the potential of a mobile gaming experience—as in via a ‘smartphone’—a part of the conversation,” Evans wrote.

Legislators passed a new law in June 2021 outlawing more betting on historical horse racing, stopping Luckii.com cold.

But the Racing Commission had another plan. Even as Luckii.com got mothballed, the Racing Commission was working with Dutch Bros Coffee founder Travis Boersma, who wanted to revitalize racing at his hometown track, Grants Pass Downs, by adding 225 historical horse racing machines. (They would be actual terminals, rather than the internet-based gambling Luckii.com offered.)

“When Travis came out of the woodwork, it was manna from heaven,” says Charles Williamson, the ORC chair. “But the tribes squashed that.”

Tribes complained to Gov. Kate Brown that the Racing Commission was moving toward a major expansion of gambling with no consultation. Brown agreed. On Feb. 11, 2022, the Oregon Department of Justice killed the proposal.

“The planned concentration of 225 electronic gaming machines offering games of chance constitutes a casino,” the DOJ wrote in a legal opinion. “Therefore, [the plan] violates the constitutional prohibition against casinos.”

Williamson says the DOJ got it wrong.

“We were very upset,” Williamson says. “It was a terrible decision, totally political. We are upset about it still.”