An incendiary legal notice filed against Portland Fire & Rescue Chief Sara Boone and the city of Portland offers a view inside the insular bureau at a time when it is under pressure to change the way it operates—and struggling to manage its budget.

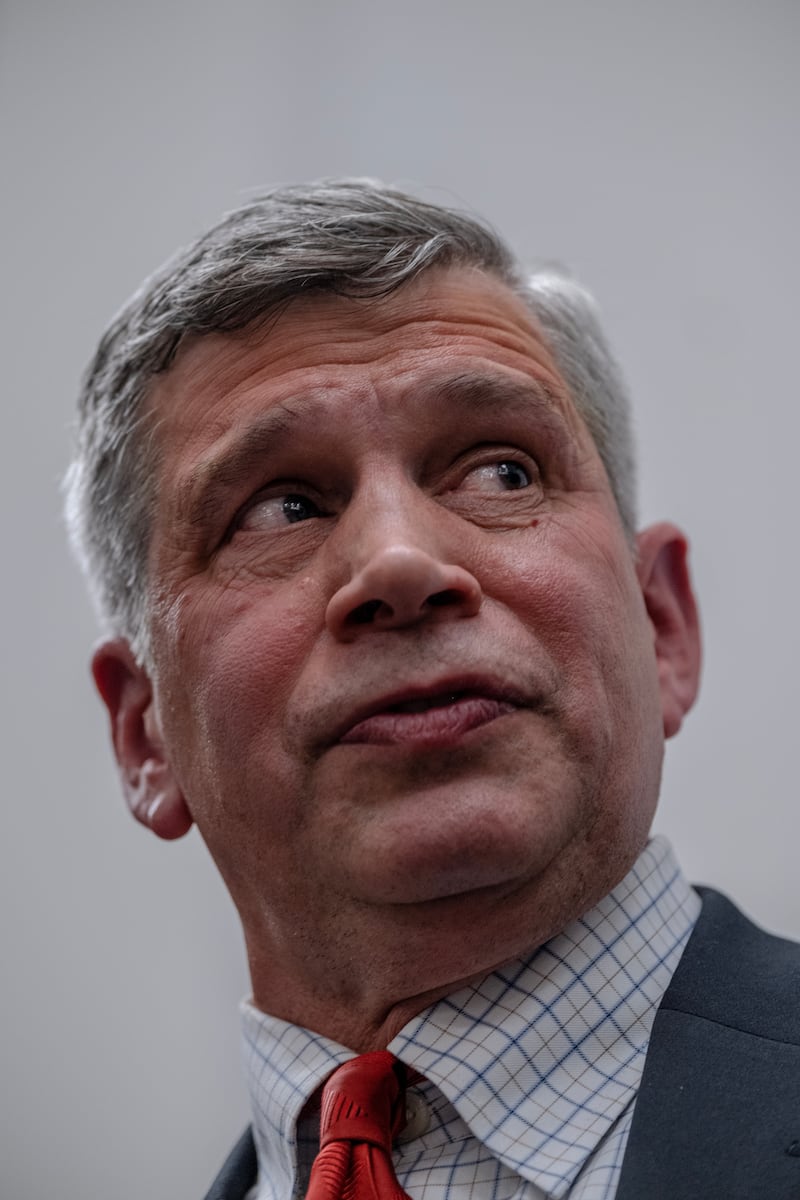

The tort claim notice, a document that is the precursor to a lawsuit, was filed March 2 on behalf of Division Chief Tim Matthews and only recently obtained by WW.

In it, Matthews alleges he disciplined a senior bureau officer and close friend of Chief Boone’s for belittling Portland Street Response employees over the use of personal pronouns—and the chief responded by sabotaging his career.

That would be explosive enough, but Matthews was overseeing the fire bureau’s highest-profile initiative: Portland Street Response, which sends mental health first responders and medics to aid people in crisis. PSR staffers say Boone sidelined Matthews, the bureau’s highest-ranking champion for their work.

And Matthews alleges in his filing that Boone didn’t want Portlanders to know how unpopular the program was inside the fire bureau.

That claim takes on greater significance during budget season, when Portland Street Response’s budget is getting cut as Boone struggles with spiraling overtime costs for traditional firefighters.

Indeed, City Commissioner Rene Gonzalez, who oversees the fire bureau and has so far proven fiercely loyal to the firefighters who endorsed his election last year, is signaling that he’s open to sending Portland Street Response—a program developed by his predecessor, Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty—to Multnomah County or a nonprofit contractor.

“The homelessness crisis has forced the city into a number of services it has not historically provided,” Gonzalez says. “We are evaluating the appropriate long-term place for PSR as a part of that work.”

In 2019, Hardesty named Boone Portland’s first Black female fire chief. In 2021, Boone placed Matthews, a former police officer, in charge of the bureau’s new Community Health Division, which included Portland Street Response.

Matthews, who joined the fire bureau in 2005, was a protégé of Boone’s. Before he went on leave in December, Matthews often acted as Boone’s designated stand-in when she was unavailable. That was before everything blew up.

In March 2022, Matthews alleges, Deputy Chief Lisa Reslock, whom the tort claim notice calls a “close friend” of Boone’s, engaged in what fire bureau employees said in complaints were “bullying, discrimination and unwanted physical contact against employees based on their sexual orientation.”

The tort claim describes an incident in which Reslock threw up her arms and said, “Really?” when an employee suggested people introduce themselves using their preferred pronouns, then put her hand on an employee who objected to Reslock’s attitude and threatened to fire that employee. (Reslock declined to comment.)

Matthews’ tort claim notice says that “because Chief Boone was a close friend of Deputy Chief Reslock, she recused herself from the [investigation] process and Deputy Chief Matthews became the decision maker” and “as the investigation proceeded, multiple new allegations were uncovered.”

Matthews, as Reslock’s direct supervisor, was tasked with deciding discipline for Reslock. He decided to fire her, the tort claim notice says. But before he could do that, Reslock “suddenly retired,” on Nov. 24, 2022.

Matthews, who, along with his attorney, declined to comment, claims in his filing that holding Reslock accountable effectively ended his career at the fire bureau. He alleges that Boone went from having tentatively offered him a new assistant chief’s job Nov. 1 to being “angry and accusatory” in a Nov. 28 meeting to discuss Reslock’s departure and then stripping him of many of his responsibilities.

(Boone declined to address the specifics of Matthews’ tort claim notice because it is pending litigation, but says “the bulk of its claims were found to be unsubstantiated by a third-party investigator hired by the city’s Bureau of Human Resources.”)

Matthews alleges Boone rescinded his promotion and yanked a Portland State University evaluation of Portland Street Response from the Dec. 2 agenda of the Portland City Council.

In his tort claim, Matthews singles out a sentence from the PSU report he suggests Boone didn’t want the City Council to see: “The relationship between [Portland Street Response] and PF&R has been fraught due to the differences in culture between the programs.”

Portland Fire & Rescue remains largely male and white—89% male and 79% white, according to a 2022 audit. It’s a traditional, hierarchical organization while Portland Street Response employees are the opposite.

PSR, patterned after a long-running program in Eugene called CAHOOTS, launched in 2021, sending mental health crisis responders and EMTs rather police to respond to 911 calls about Portlanders in crisis. It gained widespread acclaim locally and quickly became a national model.

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) likes CAHOOTS and Portland Street Response so much that in 2021 he and Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) secured nearly $1 billion in Medicaid reimbursement funds for such services to be spread across the nation.

Portland officials have struggled to connect to that new federal funding stream, however, leaving PSR vulnerable to the vagaries of fire bureau politics and budget issues, both of which Matthews’ tort claim notice underscores.

When it was finally released in December, the PSU evaluation of Portland Street Response emphasized the antipathy some firefighters felt for PSR.

“We also heard from a number of firefighters that they are wary of the differences in culture between the programs and would be apprehensive to hang out with PSR at their stations, or to work with PSR on scene while responding to calls,” the report said.

Fire Commissioner Gonzalez agrees there is a split. “There are very real cultural differences between PF&R and PSR,” he says. “There is a police abolitionist wing within PSR. While city employees are free to exercise their constitutional rights outside of working hours, there is no place for police abolitionist policies within a bureau I oversee, and we expect our first responders to work with each other as a team.”

That cultural tension is intensified by a money crunch.

Virtually all of PSR’s calls would otherwise be Portland Police Bureau calls. Narrowly speaking, that means money from Portland Fire & Rescue’s budget is covering another bureau’s responsibility. And the fire bureau is struggling financially.

A March memo from the City Budget Office calls out the biggest problem: a continuing failure to manage overtime costs, expected to balloon to nearly $23 million this year—about $6 million over budget. (For context, the Police Bureau, whose budget is 44% larger than fire’s, will spend $18.3 million on overtime.)

Chief Boone says the overtime is a function of being understaffed. “To reduce overtime and meet our service requirements, we will need to hire more firefighters,” she says.

Along with Portland Street Response, Matthews also oversaw a bureau initiative called Community Health Assess and Treat, aimed at so-called frequent flyers who overuse 911 and emergency services.

In 2021, Boone and Reslock convinced CareOregon, the state’s largest Medicaid provider, to fund CHAT, which employs about 30 workers, most members of the firefighters’ union. (Portland Street Response employs about 50. Only a few belong to the union.)

The CareOregon money runs out in September. And supporters of Portland Street Response, speaking on background, believe it will bear the brunt of the fire bureau’s cultural animus and the stronger institutional support for the CHAT program, which reduces call volume for firefighters.

PSR’s budget is set to shrink from $13.2 million this year to $10.1 million in 2023-24, according to city figures. Boone denies that money is being shifted from Portland Street Response to backfill the overtime spending. “We are currently seeking external funding sources for the PSR and CHAT programs,” she adds. “Both programs will need additional funding streams.”

Meanwhile, Boone has replaced Matthews with Division Chief Ryan Gillespie, a traditional firefighter who PSR employees say is unsupportive of their mission. And discussions about moving PSR to the city’s Community Safety Division fizzled.

Fans of Portland Street Response, from Wyden down to local officials, want to see it flourish. “It’s crucial that programs like Portland Street Response work with the state and with community care organizations to get access to the enhanced Medicaid match as soon as possible,” Wyden says.

State Rep. Rob Nosse (D-Portland), who chairs the House Committee on Behavioral Health and Health Care, says PSR is a critical asset to the city that he hopes will expand rather than contract.

“There’s enormous value in sending trained responders to help people in the throes of a mental health crisis,” Nosse says. “It’s way better than sending a police officer—and it frees up that officer for a more appropriate policing situation.”