More than almost anything, Frank Moscow wants to pick up trash along Portland’s interstate highways.

Moscow, a retired executive recruiter turned venture investor, is the founder of AdoptOneBlock. Like SOLVE, a nonprofit that arms citizens with pickers and bags, AdoptOneBlock aims to clean up streets. Unlike SOLVE, AdoptOneBlack doesn’t do cleanup events. Instead, Moscow asks his 7,600 volunteers to become custodians for a single block and keep it clean all the time.

Moscow says his trash army is spoiling to deploy on Interstates 84, 205 and 405 because stretches of all those freeways still look like dumps, while neighborhood streets are improving. But anyone picking up garbage along the highway can be charged with trespassing, he says.

“As a nonprofit organization, I’m going to get my backside sued six ways from Sunday if I encourage people to trespass,” Moscow says in an interview.

Most of all, Moscow wants to clean up the route from Portland International Airport to downtown, which looks particularly bad to both Portlanders and tourists.

Of course, Moscow would like the Oregon Department of Transportation and the Portland Bureau of Transportation to do the job themselves, but he doesn’t think that’s going to happen. Same with the Union Pacific Railroad, which owns the graffiti-covered Steel Bridge and lots of trash-filled right of way.

“The people that own the largest, most visible tracts of land are not cleaning it up,” Moscow says.

PBOT or ODOT should dedicate a truck and three employees to interstates within Portland. He understands they couldn’t displace homeless people in medians, but they could clean up around camps.

“Imagine the psychic value for the city of keeping the 405 loop clean,” Moscow says.

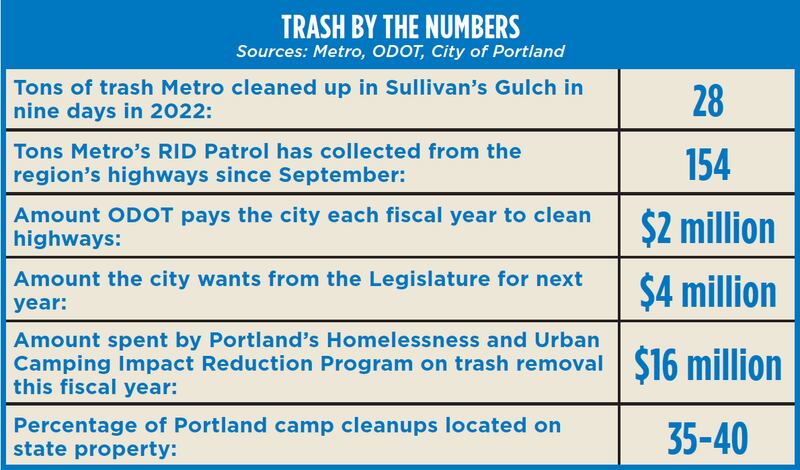

The agencies responsible for cleaning up Portland say Moscow is wrong because they are doing their part (see chart). And picking up trash is harder than it looks, particularly in a place like Sullivan’s Gulch, along I-84, where workers have to rappel down steep slopes into blackberry bushes filled with biohazards.

“It’s steep, it’s gross, and it sucks,” says Nick Christensen, a spokesman for Metro, the Portland area’s regional government.

“While trash can be found temporarily on the sides of the highway, we do not let trash pile up on our properties,” ODOT spokesman Don Hamilton says. “We work with organizations and local governments to keep our highways as clean as possible.”

ODOT has invited AdoptOneBlock to seek permits to clean safe stretches of highway, Hamilton says.

Moscow calls the permit idea “total BS.”

The permitting process, he says, requires one permit for each location, each time, with 48 hours advance notice for each permit “and a host of other onerous requirements that have everything to do with serving the bureaucracy and nothing to do with either safety or keeping a place clean. Their requirement would literally mean thousands of permits per year, which neither we, nor they, have the capacity to manage.”

ODOT and the city have been brawling over cleanups of homeless camps, the sources of much of the refuse. The city took over camp cleanups from ODOT in 2019. It gets $2 million a year from the state to do it, but Mayor Ted Wheeler wants ODOT to double that because some 40% of cleanups in Portland are on state property.

“We are contracted by the state, and our teams work directly with ODOT,” mayoral spokesman Cody Bowman says. “As the problem has increased, we are asking ODOT’s commitment to be at scale.”

The increase needs the approval of the Oregon Legislature, where business is at a standstill because Senate Republicans aren’t showing up for work.

Moscow says he’s tired of excuses: “They are better at making excuses than they are at cleaning up.”