Gov. Tina Kotek and U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) are exasperated with the scale of untreated substance abuse on the streets of Portland, where both began their political careers.

A May letter newly obtained by WW expresses a rare level of frustration, as two of the state’s top elected officials exhorted Multnomah County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson and Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler to do more to fix what they called a “crisis.”

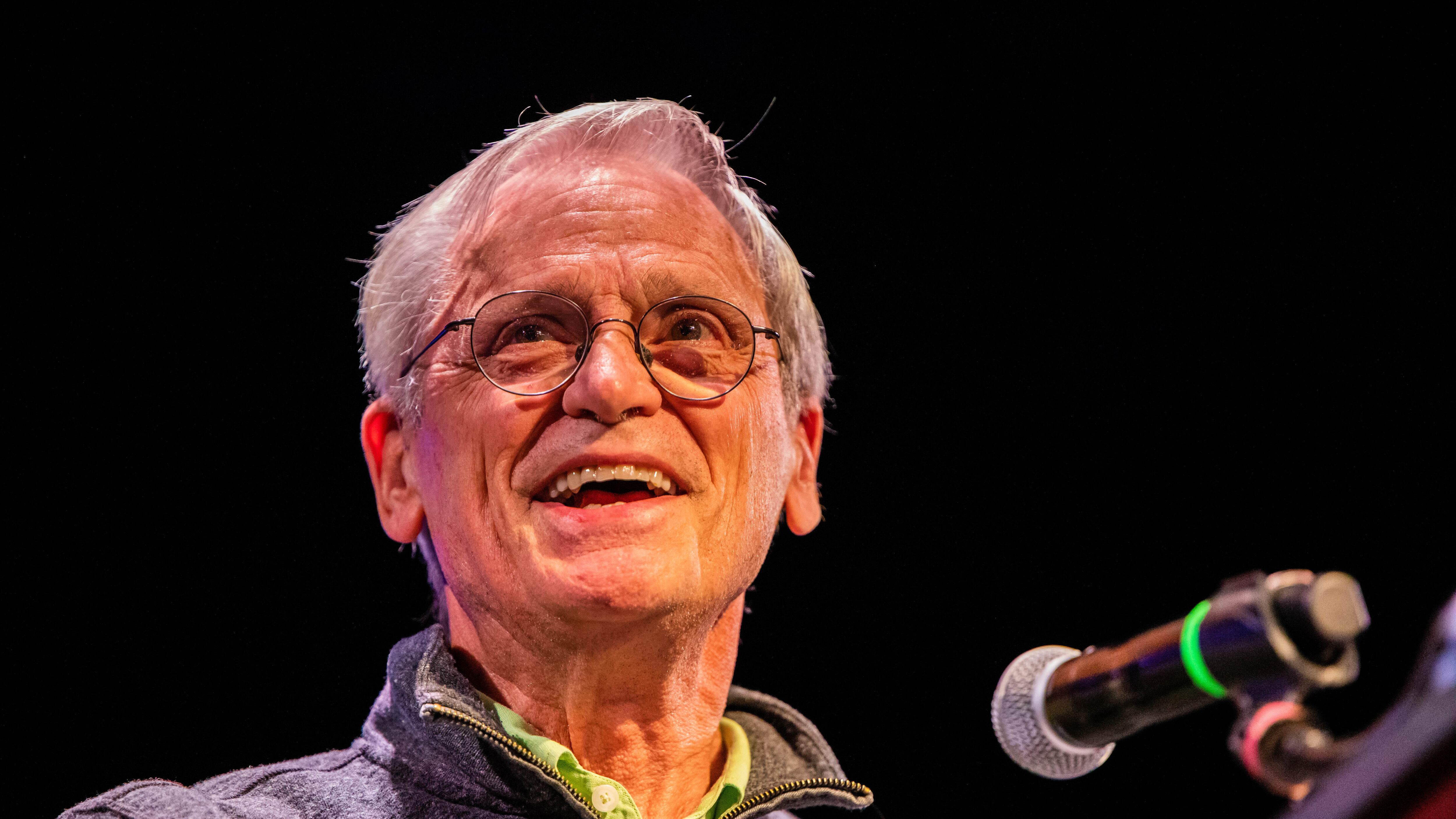

After a meeting of about 40 political, health care and public safety officials that Blumenauer convened in late May, the governor and the congressman told Vega Pederson and Wheeler they wanted “a change in strategy.”

“We urge that this response include designating one individual to lead the response to the addiction crisis across your respective enterprises,” they wrote, adding, “We do not have the luxury to have competing, duplicative, or uncoordinated efforts.”

And they set a deadline for progress: 60 days after naming a drug czar.

At the center of Kotek and Blumenauer’s ire is the rampant drug use on Portland streets, exacerbated by a sluggish, uncoordinated attempt to revive a sobering and detox center, missing from Portland since the end of 2019.

On June 5, Vega Pederson and Wheeler pointed fingers back at Salem and Washington, D.C. “We can attest to the rampant fentanyl and polysubstance drug use and overdoses that have decimated parts of our community over the past two years,” they wrote. “However, the cascade of problems we face emanate from decades of state and federal inaction and neglect.”

The local officials’ letter, which comes on the heels of both the county and city approving record budgets, cried poverty: “No single jurisdiction (including both City of Portland and Multnomah County) is adequately funded or staffed to address the rapidly evolving challenges we face.”

And it pushed Kotek and Blumenauer to “identify state funding to launch the first phase of implementation of the Behavioral Health Emergency Coordination Network.”

Politicians traffic in acronyms, but the request for funding for BHECN—think of it as a sobering and detox center for people too drunk or addled by narcotics to function—lays bare a growing tension among top officials and explains why first responders, emergency rooms, and the public are overwhelmed by chronic substance abusers.

The frustration comes at a time when the Joint Office of Homeless Services budget for 2024 is $279 million—not counting $50.3 million in unanticipated receipts that the regional government Metro will soon pass along—and the city has untapped Medicaid funding available to help pay for Portland Street Response to address mental health crises.

Blumenauer says he left the May meeting about Portland’s streets with a clear understanding. “The consensus of all these experts we brought together is that money is not the problem,” he says. “The question is how we mobilize and utilize the resources we’ve got.”

Back in the 1990s, when methamphetamine was made in bathtubs and nobody in Oregon had heard of fentanyl, a Central Eastside “sobering center” where people could sleep off booze or narcotics served as many as 20,000 people a year, according to a consultant’s report.

First responders and the CHIERS wagon—a van that did nothing except pick up heavily intoxicated Portlanders—dropped them off at 444 NE Couch St.

For the past three and a half years, however—even as Oregon’s substance use disorder rates stayed among the nation’s highest—the sobering center served the same number: just about none.

That’s because, in the greatest explosion of drug overdoses in Oregon history, the city and the county have not figured out how to replace the sobering facility, which closed in early 2020.

Jason Renaud of the Mental Health Association of Portland says that’s a disgrace. “There’s a desperate need,” Renaud says, “and a total lack of urgency—if the will was there, we could open one in six weeks.”

For now, people who might otherwise go to a sobering and detox center crowd into hospital emergency rooms or stay on the streets. (About 22,000 people a year visit local hospital ERs for substance use disorders.)

A small ray of hope: With funding from CareOregon, the state’s largest Medicaid provider, and some city and county money, Providence Health and Legacy’s Unity Center are opening nine and eight sobering beds, respectively. But most observers see that as a stop-gap measure.

Blumenauer says he cannot recall another time in his 50 years in elected office when public funding has been so plentiful.

“The voters and the Legislature have really stepped up,” he says, “but we have a problem with too many cooks in the kitchen.”

Again, BHECN is a case in point. The nonprofit Central City Concern operated the old sobering center under contract with the Portland Police Bureau. So Mayor Ted Wheeler’s office took the first crack at replacing it, first hiring a consultant to study the need. That led to a request for proposals last October to operate a new 50-bed sobering and detox center that would serve about 10,000 people a year.

No organization responded. So the county took over, hiring a consultant of its own.

A June Zoom call with interested parties left many participants scratching their heads because instead of sketching a vision that could, for instance, combine plentiful local funding with cheap office space, the county’s consultant described a seven-year procurement process.

Blumenauer, among others, was hoping for something more concrete and urgent. “Excuse me, seven years?” he said. “What about now?”

Vega Pederson says critics misunderstand the county’s vision: It wants to procure services lasting for seven years, not take seven years to get services in place.

“Plans, funding and capital projects will happen much quicker than that,” she says. “The decision to stand up a seven-year procurement rather than a more standard five-year procurement will extend the eligibility of the partners who are identified and it will diminish the red tape of procurement.”

Although Vega Pederson has acknowledged her frustration with the Joint Office of Homeless Services’ dramatic underspending of Metro supportive housing services dollars ($43 million through the first three quarters of last year), she says using one-time money to launch BHECN isn’t a solution.

“Voters didn’t pass the SHS measure to backfill state and federal responsibilities,” she says. “Voters expect those funds to pay for homeless services, and they expect other partners to do their part so we can collectively expand every part of the system.”

Indeed, she would prefer Blumenauer and Kotek to focus on bringing more resources to the county rather than telling her and Wheeler how to do their jobs.

“I was taken aback,” Vega Pederson says of the May letter. “Asking for a drug czar was jarring, especially because the mayor and I agree our governments work well together on that issue.” (Wheeler’s spokesman, Cody Bowman, says the mayor’s reaction to the letter was similar. Bowman adds the city is contributing $1.9 million in ongoing funding to the BHECN and Wheeler’s office co-chairs its executive committee.)

But even at county headquarters, the push for urgency is growing. “When I talk to first responders, they say there’s nowhere to take people in crisis,” says the county’s newest commissioner, Julia Brim-Edwards. “Everything is taking such a long time, and there’s no plan.”

Vega Pederson promises she will change that and points to her newly passed budget, which includes a big boost in behavioral health spending and $2 million for BHECN, which she pledges will take a big step forward in September, when respondents have told the county which services they can provide.

“One of my top priorities when I took office in January was addressing the shortage of sobering services, as well as all other elements of our behavioral health system,” she says. “There are a lot of people willing to point fingers, but I am committed to getting things back on track.”