If you want to buy fentanyl in downtown Portland, the choice spot is the corner of Southwest 6th Avenue and Harvey Milk Street. The market opens at 6 pm, after cops and commuters go home to their families.

The sellers are kids who wear black ski masks and look barely old enough to drive.

On any given evening, this downtown intersection, ringed by some of Portland’s swankiest hotels, is manned by a half-dozen dealers peddling the most dangerous drug in America.

Buyers smoke “fetty” in the stoop of the nearby Three Kings Building, the former bank and historic landmark that is now nearly vacant.

Dealers chat with passersby on the corners as lookouts stand watch behind. Some carry guns, which they’re known to occasionally fire skyward in battles over turf. Men roll by on bicycles, hawking groceries and consumer electronics. Trash sweepers tasked with cleaning the sidewalks push rolling bins, filled with collected needles and tinfoil, down the sidewalk.

For the past month, WW has been observing this corner, which is now ground zero for Portland’s fentanyl crisis. Here, a drug manufactured by Mexican cartels is sold for small bills. When pure, it’s 100 times more powerful than morphine. This intersection, and the people who frequent it, are at the center of a myriad of crises facing not only Portland, but the nation: an epidemic of addiction and homelessness, understaffed and beleaguered first responders—and a staggering number of deaths.

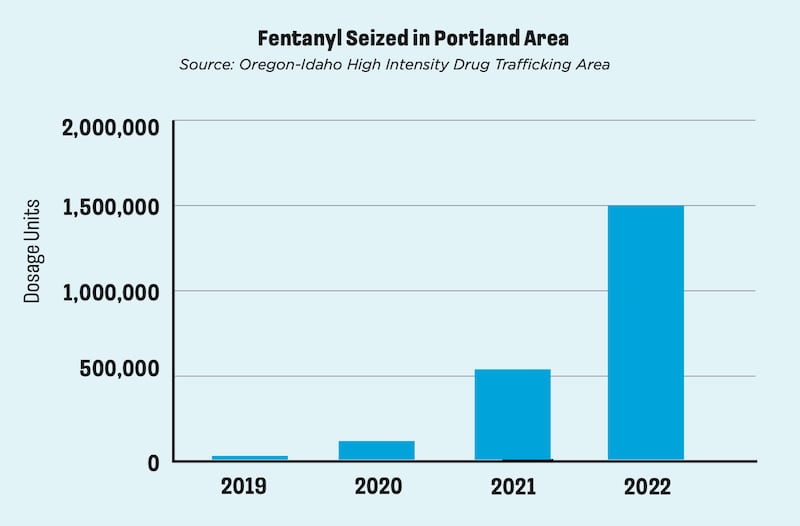

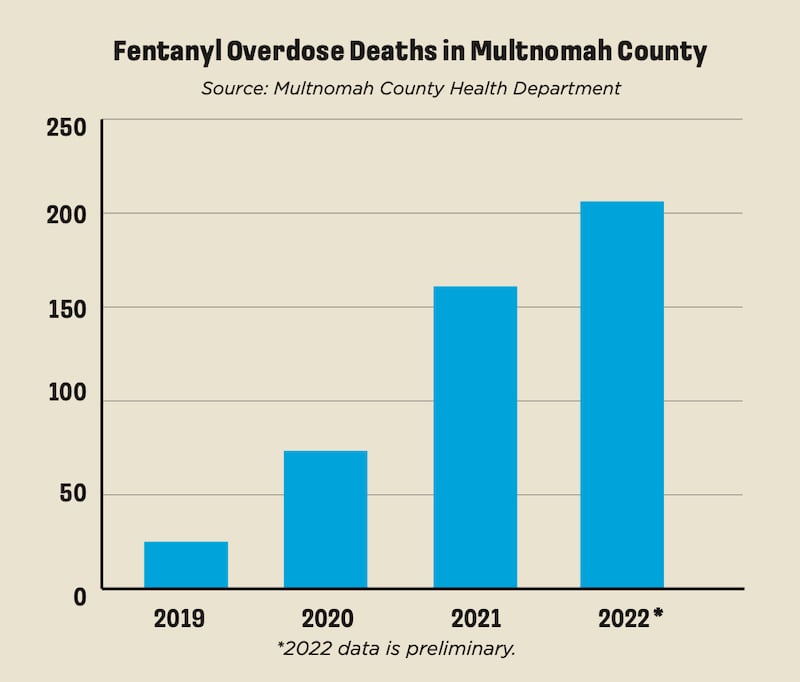

Overdoses have surged in Portland over the past few years. Last year, the Multnomah County Medical Examiner’s Office recorded more than 350 overdose deaths involving opioids, nearly triple the number only three years earlier, an increase driven by fentanyl. Oregon has the highest rate of drug use disorder in the country, and the fastest-growing fatal overdose rate among teenagers.

The sale and use of opioids in downtown Portland is a perennial story, featured on the cover of WW since the 1970s, when the Rose City became a heroin hot spot. What’s different about the fentanyl market is the potency of its product.

What’s now being sold on this corner is a drug so powerful and unpredictable that observers can watch its victims collapse within feet of obtaining it. Unlike with heroin, every hit can be a potential overdose. The people who use it choose between risking their lives with each injection, or smoking it, which often means brutal withdrawal symptoms within hours, making daily life a constant battle to stay “well.”

Ryan Lufkin, who prosecuted drug crimes for the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office a decade ago, says the roots of Portland’s fentanyl problem go back more than 10 years to when pharmaceutical companies flooded the county with powerful prescription opioids like OxyContin. Once people became addicted, they turned to a cheaper alternative, heroin.

In 2009, there were 94 overdose deaths in Multnomah County. Lufkin was alarmed by the rising number. But it was just the first stage of an opioid crisis.

The latest escalation is fentanyl, which is commonly found in counterfeit pills, called “blues,” that mimic the appearance of the prescription opioid they replaced.

This is the story of the corner that leaches this poison into the city—and, on one weekday evening, the consequences.

As recently as last year, Portland’s drug market was centered in Old Town. Drug deals were a daily nuisance, recorded in reports from occasional police stings that describe the nearby bus mall and its surrounding environs as “crack alley,” a parking lot called the “boneyard,” and the “benzo benches.”

Spurred by complaints, Mayor Ted Wheeler and the neighborhood association agreed in March 2022 to a crackdown, marked by an increased police presence and subtle streetscape shifts. The notorious wooden benches along Northwest 5th Avenue disappeared.

Thus began a game of whack-a-mole, migrating southward. First, the drug trade moved to the parking lot outside Dante’s. Then to Washington Center, a vacant office complex at the busy corner of Southwest 4th Avenue and Washington Street. And when the center was boarded up earlier this year following WW’s reporting on the state of its surrounding sidewalks, the fentanyl market moved west, to Southwest 6th Avenue.

The shift of Portland’s drug market toward the downtown core coincided with the arrival of a new group of dealers.

They arrived downtown over the winter, on standup scooters wearing matching backpacks. Portland police believe they are dispatched from suburban safe houses, distributing fentanyl produced with Chinese chemicals in superlabs operated by Mexican drug cartels and shipped up the Interstate 5 corridor. Many have told police they’re from Honduras.

There’s a hierarchy to the international drug trade. While Mexican cartels do the manufacturing, the dirty work of selling and moving the drugs falls on young men, often immigrants fleeing poverty in countries like Honduras, with little if any connection to the cartels that supply their product. In San Francisco, they’re known as “commuter drug dealers” due to the fact that they tend to stay in the cheaper East Bay and take the BART downtown.

Here, investigators have uncovered safe houses across the Willamette Valley. Two Honduran men were arrested earlier this year moving pounds of fentanyl from California through a house in Gresham.

Another thing: Although many buyers and cops refer to the dealers on the corners as “the Hondurans,” it’s not clear how many actually are. To be sure, people of all races sell fentanyl downtown. And while San Francisco’s mayor has said “a lot” of their dealers are from the Central American country, such a trend isn’t clear in Portland from arrest records.

Twenty-one-year-old Reinel Raudales-Escalante, however, is Honduran.

Raudales-Escalante has been arrested a half-dozen times in Multnomah County just in the last year, mainly for selling fentanyl, and parts of his life story can be pieced together through court interviews. His primary language is Spanish, and he spoke to authorities through an interpreter.

Raudales-Escalante grew up in central Honduras, left school in sixth grade, and lived for two years in Georgia before arriving in Portland last May. He was earning minimum wage packing vegetables.

The first time he was caught dealing fentanyl was last August, at the benzo benches in Old Town. He was picked up near Dante’s in January and, by February, had moved downtown to Washington Center.

He claimed he was homeless, living on the streets of Gresham. The jail interviewer was skeptical of that claim, noting inconsistencies in his stories. Some of the dealers are juveniles. One person familiar with investigating drug trafficking operations in Portland has a theory: They’re being exploited by higher-ups who know there’s little consequence if the kids are caught.

Over the past year, Raudales-Escalante has been charged with drug crimes six times. His most recent arrest occurred after he was doing doughnuts in a BMW outside Pittock Mansion, nearly hitting nearby pedestrians, before leading police on a high-speed chase through the West Hills.

He was indicted by a grand jury twice, paid more than $2,000 in bail, and then failed to report to pretrial supervision. A warrant is now out for his arrest.

Why don’t police break up the drug market?

In fact, they do make arrests. One recent afternoon, the Central Precinct’s bike squad pulled up to the corner. Officer Eli Arnold, who’s made a specialty of spotting dealers, was watching the action from a neighboring building. Cops arrested 36-year-old Rey Maudiel, who told police he had just arrived in town after meeting a man in Los Angeles who recruited him to sell dope in Portland. Maudiel said he commutes downtown on the MAX from Gresham. A warrant was out for his arrest on drug charges in San Francisco.

The four-member bike squad, tasked with addressing livability problems in Portland’s downtown core, has become the city’s de facto street drug enforcement team.

Spotting dealers has gotten easier, Arnold says. “After [Measure] 110, everyone started doing drugs out in the open without even trying to hide it. Suddenly, it became super productive. You can wait 10 minutes and see a drug deal. I started doing it all the time because it was working.”

He set up shop in a vacant office building overlooking Southwest 5th Avenue. Thanks to Arnold’s binoculars, he says, the squad arrested more than 20 dealers early this year. But the numbers have dropped off since.

The bike squad works only the day shift, which ends at 5 pm. “They know when we leave,” Officer David Baer says.

The Central Precinct once had a street crimes unit that patrolled downtown after the bike squad went home. But the Portland Police Bureau, facing staffing shortages, disbanded it years ago.

Even with the reshuffling, the precinct still routinely operates with staffing at a minimum, sometimes significantly so. The precinct requires 17 officers on patrol to safely respond to 911 calls during the afternoon shift, the Police Bureau says. On one recent afternoon that WW was downtown, there were 12.

The result: The Hondurans roll in at 6 pm and sell in peace.

Robert is a 33-year-old man with piercing blue eyes and tightly cropped brown hair who grew up in a small town in Eastern Washington. He was introduced to opioids as a teenager when a neighbor handed him a fistful of prescription pills in exchange for mowing her lawn. Eventually, he started injecting heroin, which helped numb the pain after his best friend died of an overdose and his mother died of cancer.

When the veins in his arms collapsed, he switched to smoking fentanyl, “a game changer for a lot of us,” he says, because of how easy it was to get a cheap high.

How easy is it to purchase fentanyl in downtown Portland? I ask Robert for some tips.

First, he explains, avoid “blues,” the pills that are stamped to look like prescription OxyContin. They’re fake and the dosage is weak. They’re as cheap as a buck per pill on the streets.

Instead, he says, ask for “fetty,” the powdered fentanyl that’s surged in popularity in the past year. And, if I don’t want to be ripped off, make sure I ask for it “clean.” It’ll cost more, between $30 and $60 a gram, but you’ll get a stronger product, he says.

I decide I can do without the clean stuff.

“Fetty?” I ask one of the Hispanic youths. He nods, pulling a small plastic bag of white powder out of a sweatshirt pocket.

“How much?” he responds. I hold out a $20 bill. He turns around, extracts a white rock from the bag, chips off a piece with a knife, and then drops it into my outstretched hand.

I had expected, naively, for him to hand me the baggie. Instead, the loose rock is now dissolving in the sweat of my palm. I drop it into my pocket and run to a water fountain to rinse off.

WW sent the drugs to a lab, which confirmed it was fentanyl—a weak dose, heavily cut with the diuretic mannitol.

You don’t have to look far to see the consequences of the commerce happening on this downtown block.

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, at one end of the block, within sight of the dealers, a pair of men sought shelter under an eave at a branch of U.S. Bank. One of them, Jeff, sat against the wall, his arms around his legs and his hoodie pulled up far over his head.

Jeff grew up in the Portland area, he says. Found a job as a landscaper, fell in love with a girl. They planned to buy a house and get married, until she ran off to Qatar with another man. He took to alcohol, and then fentanyl.

For a while, Jeff lived with parents, until they moved to the country. Now he is homeless, constantly seeking his next high. “The daily struggle consumes your life,” he says. “You’ve got to be on top of your shit.”

The night before, he was not. He fell asleep on the sidewalk. When he woke up, everything he owned, including his drugs, money, shirts and even underwear, were gone.

It’s not the first time he’s lost everything. It happens every time the police take him to jail or the city sweeps his camp, he says. Sometimes, it’s an ex-girlfriend who hunts him down and burns his tent. Setbacks, setbacks and more setbacks. “I’m constantly restarting,” he says. “It’s not a winning battle.”

Tonight, he’s back at the corner looking for drugs, or at least a buddy who can hook him up. He’s been looking for him all night, but no luck. And he’s got no more money to buy fetty himself. He’d go to a shelter, but he knows there’s a warrant out for his arrest and he’s afraid the staff will tip off the cops. Tomorrow he’ll scrounge up some cans and redeem them for cash.

But for now, with withdrawal looming? “I’m fucked.”

As the sun goes down that night, first responders rush from overdose to overdose.

At 8 pm, cops administer Narcan to a man passed out in front of the Hi-Lo Hotel on Southwest 3rd Avenue. His name is James.

Nineteen minutes later, there’s a call a few blocks away on 1st Avenue. As the ambulance arrives, screams can be heard from an encampment under the Morrison Bridge. Another victim lies in his own vomit on the stairs, wearing nothing but a pair of overalls. A man living in a nearby tent, Endoe Parra-Cisneros, calls over the paramedics. He’s already administered Narcan.

Parra-Cisneros says he’s seen 60 overdoses in the few months he’s been unhoused.

At 9 pm, outside Washington Center, a half-dozen cops and paramedics surround an elderly man lying face up beside an overturned wheelchair on the sidewalk. His name is Gary. It takes four doses of Narcan to revive him. A piece of tinfoil and a lighter lie on the sidewalk.

The paramedics pull Gary into his wheelchair, wrap a thin white blanket around his shoulders and then leave. He is briefly alone on the sidewalk. One of Gary’s legs has been amputated. His scalp is covered in lesions—a common consequence of long-term opioid use.

At 9:21 pm, another overdose on 6th Avenue. Officer Stephen Pettey was driving his squad car to a report of gunfire on the corner when he saw a man passed out in the street.

According to data provided to WW by Portland’s Bureau of Emergency Communications, overdose and poisoning made up 6.1% of all medical calls in the first half of 2023. That’s a jump from 3.9% in the later half of 2021, the oldest comparable data due to a shift in BOEC bookkeeping.

Portland firefighter Mike Fullerton is often first on the scene to an overdose. “It’s all we do,” he says.

Robert would like a different life.

He spent a year in prison after being caught driving stolen cars. (He says his legal problems began after he moved into what turned out to be a chop shop to save on rent.) He’s now living on the street after being released earlier this year, cobbling together enough cash each day to feed his addiction.

The conviction has made getting a normal job difficult. So Robert turned to “canning.” He rides the bus every few days out to the suburbs where he collects bottles and cans from car wash trash bins, which he redeems for cash.

On a good day, it amounts to $50, which he spends on fentanyl.

On a bad day, his dealer fronts him so he can avoid the withdrawals, which are so “gruesome,” he says, they make it impossible to go out and find the drugs needed to stop them.

Exit strategies from fentanyl are hard to find. Especially in Portland.

Oregon Health & Science University researchers reported last year that Oregon has half the drug treatment beds it needs. The state lost nearly 150 during the pandemic—a “staggering” number, a top official admitted last year. Before that, in early 2020, Portland lost its only sobering center, where cops could drop off people intoxicated on booze or narcotics. City, county and state officials have failed, despite years of discussions, to open a replacement.

The result is the situation on the streets, says Jason Renaud of the Mental Health Association of Portland. “Right now, if someone wants to get clean and sober, there’s no door for them to do that.”

For Robert, who’s motivated to get clean and get off the street, the process has been frustratingly slow. He says he’s on the waitlist at the county’s new downtown shelter. And he wants to eventually enter a methadone program, where he can get a supply of the long-acting opioid used to wean substance abusers off street drugs.

But more than 40% of the people who wait in line at Central City Concern’s detox facility are turned away for lack of room. And methadone clinics are notorious for their long waitlists.

“They say there’s help for us if we want it, but it’s really not that easy to get,” Robert says. “It’s a waiting game—and a lot of people don’t make it.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to more accurately reflect what is known about the nationality of Portland’s fentanyl dealers.