Ask Gregg Colburn, assistant professor of real estate at the University of Washington, what causes homelessness, and he’ll tell you that it’s not poverty, drug addiction or mental illness.

To find the real culprit, Colburn uses a statistical method called “R Squared,” which shows how the differences in one variable can affect differences in another. In a helpful eight-minute video on the Seattle Channel, the city’s video website, Colburn graphs homelessness against drug addiction, poverty and mental illness and finds little correlation.

Those results are borne out in real life. If drug addiction caused homelessness, West Virginia, where the opioid epidemic is raging, should have a huge homeless population. But it doesn’t. Same with poverty: Detroit is the poorest city in the U.S., and homelessness isn’t rampant there.

So, what factors correlate with homelessness? High rents and low vacancies.

“What you see when you plot median rents is that in places that are expensive, homelessness is high, and in places that are cheap, homelessness is low,” Colburn says.

Seattle and Portland have high rent and low vacancy, but only one of those places is proving effective at switching those, says urban planner Alisa Pyszka, president of Bridge Economic Development and a former candidate for Metro Council president.

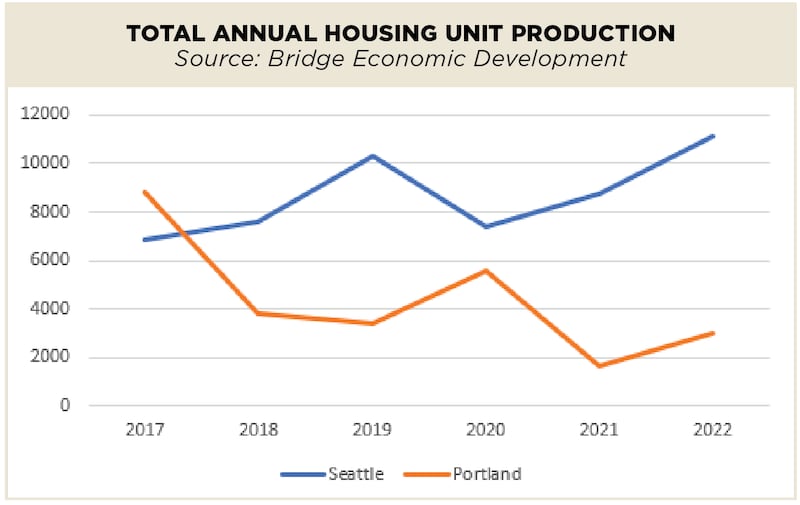

Excluding their suburbs, Portland and Seattle are similar in size. Seattle has 750,000 people, and Portland has 635,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Both cities are about 145 square miles in area, including water features. Back in 2017, Portland produced more housing than its larger neighbor, 8,835 units to 6,820, data compiled by Pyszka shows (see graph below). By 2021, Seattle was walloping Portland 8,727 to 1,639.

Reasons for that gap vary. Portland’s design review, where bureaucrats and citizens can weigh in, and construction slows to a crawl, is a factor (see “Fixer Upper”). And Pyska blames the city’s inclusionary zoning policies—but Seattle has those, too, and the rules so far haven’t dampened developers’ ardor.

The bottom line is that Seattle is building more housing of all kinds, which, if Colburn at UW is right, should lead to lower rents and less homelessness. Time will tell.