The Oregon Public Employees Retirement Fund, one of the oldest, biggest investors in private equity, is understating the risk of investing heavily in funds that buy whole companies using borrowed money, according to the financial analyst who revealed Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme.

An article in the Aug. 4 edition of The New York Times describes new work by Michael Markov, a mathematician who studies financial markets.

Markov says the Oregon pension fund is over 40% more volatile than its own public reports show, the Times said. That means is it taking more risk to achieve higher returns than it has been showing in its public reports, Markov says.

Oregon was a pioneer in using private equity to boost returns in a pension fund. The state invested in a fund run by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. in 1981 when the three “corporate raiders,” as they came to be known, were just getting started. KKR became famous in 1988 when it bought RJR Nabisco, maker of Oreo cookies, for $25 billion. That deal inspired a book that defined 1980s greed, Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco.

The business is called private equity because managers like KKR it don’t tap public markets for money. They raise it from foundations and pension funds. Private equity has come under fire from critics because managers often borrow billions of dollars to buy companies and then freight the target firms with that debt, causing them to fail. Medford-based fruit seller Harry & David went bankrupt in 2011 after a firm called Wasserstein & Co. bought it with $200 million in borrowed money that the company couldn’t pay back.

The problem with private equity, Markov says, is that the companies owned by KKR and others usually don’t trade on public markets, so there isn’t an up-to-the-minute way to see how much they are worth, compared with, say, Boeing Co. or Nike Inc.

Instead, the Times said, the value of companies owned by private equity firms are based on “infrequent appraisals.” Those assessments give private equity the illusion of low volatility and lower risk, the Times said, quoting Markov’s work.

“When you adjust for the stale pricing in private equity funds, the risks are much greater,” Markov told the Times.

And Oregon is at bigger risk than most pension funds because of its private equity load, the Times said. As of April 30, Oregon had $25 billion in private equity funds, or 27% of its total $93 billion, according to public records, making private equity Oregon’s biggest investment by category.

“On average, the risks being carried by public pension funds are at least 20 percent greater than they are reporting, largely because they aren’t taking account of the true risks embedded in private equity,” the Times wrote, citing Markov’s work. “Oregon’s pension fund is over 40 percent more volatile than its own reported statistics show.”

The Oregon pension system declined to comment on the matter, the Times said.

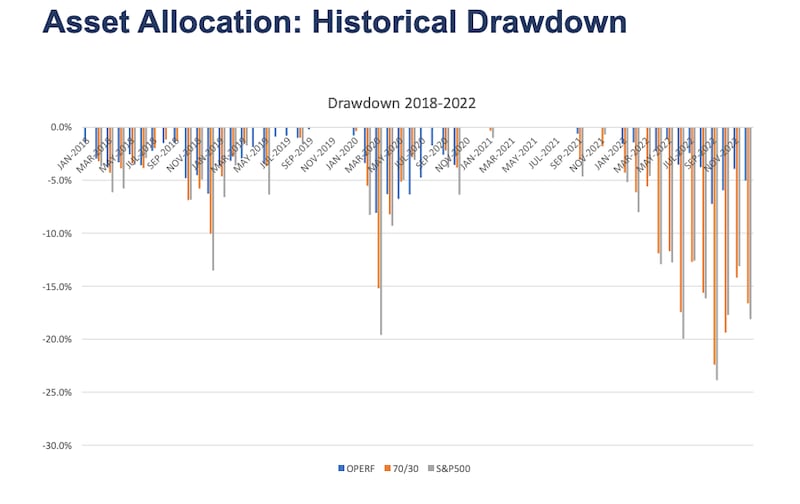

Contacted by WW, Oregon State Treasury spokeswoman Amy Bates declined to comment on Markov’s work specifically. The Treasury analyzes risk in ways beyond what is presented in its public quarterly reports, she said. Like other pension funds, it determines risk using standard deviation, a measure of volatility, and by examining “drawdowns”—industry jargon for losses.

A chart from a Treasury presentation in April shows Oregon’s portfolio sustaining far smaller monthly losses than both the Standard & Poor’s 500 index and a portfolio that is 70% stocks and 30% bonds.

“We recognize [Markov’s[ disagreement with our reported portfolio volatility and would concur that the reported volatility of monthly returns likely understates risk, largely due to our allocation to private markets,” Bates said in an email. “However, we hope the above information helps illustrate the variety of methods in which Treasury and the OIC measure portfolio risk and the frequency in which information is reviewed and shared, beyond the quarterly fund reports published on the website.”

An example of one of Oregon’s private equity deals came to light last month. The fund committed $750 million to KKR North America Fund XI in 2012. The fund used some of that money—and money from other pension funds—to buy American Medical Response for $2.4 billion in 2018, then combined it with another company, Air Medical Group Holdings, to form Global Medical Response. GMR, through AMR, is the ambulance provider for Multnomah County and many other localities.

Since then, the value of Global Medical bonds have plunged amid concern that GMR won’t be able to repay the debt foisted on it by KKR. In April, S&P Global Ratings cut its rating on GMR’s loans and bonds to CCC+, a “junk” rating that reflects those concerns.

“The downgrade reflects our view that GMR’s capital structure is unsustainable over the medium to long term,” S&P wrote in its downgrade. “We believe GMR highly depends on a multitude of favorable conditions—including moderating labor and fuel costs, weather, and improving capital markets—to meet its financial commitments over the next 12-24 months.”