Here’s a scary number: Nearly a third of Portland’s downtown office space stands empty.

The skyline along the Willamette is a ghost town of skyscrapers, filled with buildings that are in trouble because they have too few tenants. Or they have loans that are coming due and can’t refinance. In far too many cases, it’s both.

Such grim circumstances are outlined in some harrowing documents being passed among Portland commercial property owners these days. The spreadsheets are known as “death lists” because they describe buildings that don’t make economic sense any more. They have too much debt and not enough income from rent to cover it.

The death lists include phrases like: “deed in lieu of foreclosure” (meaning the owner voluntarily gives the property to the bank); “expected to go back to the bank”; or on a “watchlist” because the loan matures soon.

To a real estate professional, such terms are tantamount to seeing words like “stomach cancer” or “genital herpes” in an email from your doctor. No one wants to be on such a list. But the ones being passed around town contain more than three dozen buildings, some of them really large.

So we made a list of our own.

WW got hold of a copy of one death list and spent hours at the county recorder’s office looking through addresses for bad loans, foreclosures, opaque transfers and liens. We made neat stacks of paper on our office floor and coded them to names on a Google Sheet that tracks owners, prices paid, and market values. We traced ownership through endless lists of nested limited liability companies, which property owners use to cloak their holdings. We called and emailed dozens of owners from Florida to Los Angeles—and heard little back.

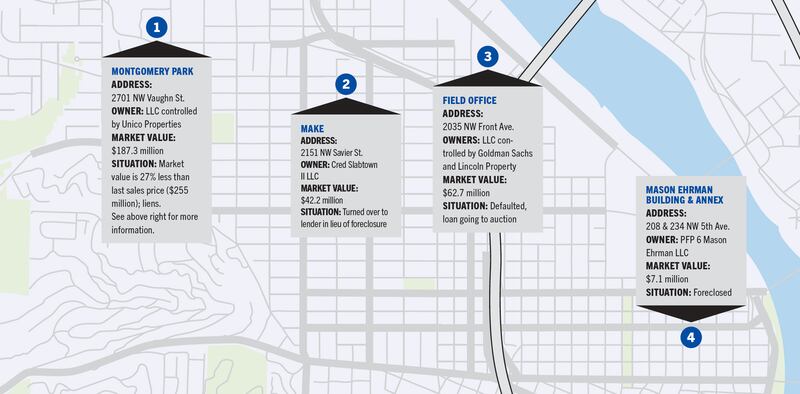

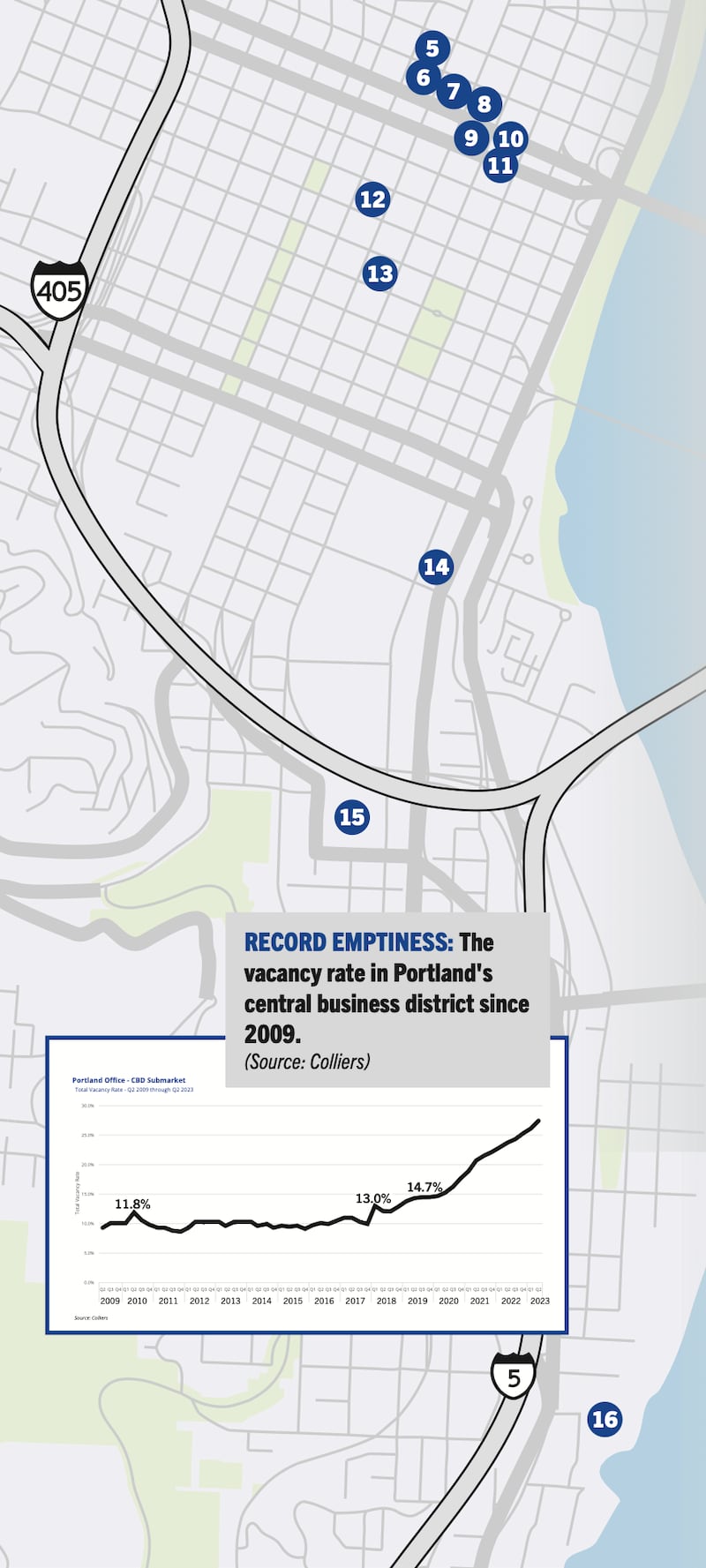

From that we created a map showing properties where we could document anything that smelled like distress: something as mild as a lien or as catastrophic as a foreclosure. The upshot: We found 16 properties that have a documented problem now.

It’s no secret that there are troubled buildings all over Portland. They’re all over America, thanks to the pandemic, when companies figured out that employees could work from home in a pinch. Those workers have been slow to come back—slower in Portland than in most cities, by several measures—and many companies aren’t renewing office leases.

In a case of very bad timing, many real estate loans made during the last boom, when interest rates were low, are coming due now. Owners must refinance, but their buildings are worth far less, and interest rates are much, much higher. That’s a deadly pair of pincers. Many owners are choosing to walk away, giving buildings back to the banks that financed them. An LLC controlled by Bank of America, for example, took over the Crossing at First in May—a gleaming 191,000-square-foot campus near Duniway Park that was remodeled in 2017.

“A slug of loans is all coming due at the same time,” says real estate lawyer Dean Alterman. “The people I’m dealing with can still get financing, but they have to look harder for it.”

The question—and it’s a contentious one—is whether Portland is worse than any place else because of blight. Plywood that went up during the 2020 protests still obscures some downtown storefronts. Homeless camps that took root during the pandemic are only now being removed. On some downtown blocks, you’re just as likely to see someone smoking fentanyl as sipping a Frappuccino.

Bob Ames, former president of First Interstate Bank of Oregon and a longtime investor in commercial property, thinks Portland is suffering more than most. “The problem with downtown Portland is that you don’t want to be in downtown Portland,” he says. “We’ve driven a lot of capital out of here, and a lot of tenants. You’re not going to book another major employer into this city for a decade.”

Statistics support Ames, to a point. Downtown Portland’s office vacancy rate, including space available for sublet, was 31.5% in the second quarter of the year, according to Colliers, a Toronto-based firm that tracks global real estate. That’s a fraction better than hard-hit San Francisco (31.9%), and worse than Seattle (27.9%), Los Angeles (30.9%), Salt Lake City (19.9%) and Denver (23.4%).

“The Portland office market continues to face a bleak outlook at the midway point of 2023,” analysts at Colliers wrote. “Over the next two quarters, more than 500,000 square feet of leased space is set to expire marketwide. Should these tenants maintain office space following the expiration of their leases, they will likely look to downsize their real estate footprints.”

Ames, 83, says he’s never seen Portland so empty and foreclosed. “I’ve been in this business for 50 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this,” he says.

At 31.5%, Portland’s vacancy rate is higher now than it’s been since anyone started keeping reliable records. Even in 2010, after the Great Recession weeded out lots of tenants, the downtown vacancy rate stayed below 15%, Colliers says.

Just like in the movies, lurid scenes play out on the courthouse steps. Last Friday morning, one of Portland’s most iconic buildings, Jackson Tower, went to auction. The 12-story landmark, built in 1912, overlooks Pioneer Courthouse Square and has a Roman-numeral clock tower. A California-based LLC bought it for $13.5 million in 2008 and still owed $10.7 million to JPMorgan Chase, according to court filings.

At 10 am, a representative for the trustee read out the auction notice to a reporter and a photographer. No one else showed up. When neither of the journalists bid, a lawyer for the lender offered $7.5 million, using the debt on the building, which totaled $10.7 million. That’s called a “credit bid,” and it’s a bit like taking your brother to prom. No one wants to do it.

The loss of tenants is hurting older buildings like Jackson Tower most. Companies looking for space can get good deals on plush buildings that broke ground before the world changed. Law firm Davis Wright Tremaine is leaving its old digs in the Wells Fargo Tower for Block 216, a new spire that has both office space and Ritz-Carlton residences (that commute could bring a new meaning to working from home).

But some brand-new buildings are cratering, too. The owners of Field Office, a 290,375-square-foot office complex near the Willamette River with all the tech-bro amenities (roof deck, scooter charging), defaulted on their $73.8 million loan after they couldn’t find enough tenants. The lender is auctioning the loan to the highest bidder. Offers were due this week.

Because Portland has no sales tax, local governments rely more heavily on income tax and property tax to pay for things like schools and homeless shelters. And taxes paid by downtown property owners account for about 15% of Multnomah County’s property tax, according to consulting firm ECONorthwest.

Given that those taxes are levied based on the value of the buildings, if values fall far enough, so will tax revenues.

We won’t know how bad the hit is until the county assessor’s office releases the next round of market values at the end of the year, says Michael Wilkerson, director of analytics at ECONorthwest. Because property tax increases are capped in Oregon and have been for decades, the assessed value of buildings—the value that determines an owner’s tax—lags the market value. In good times, it lags a lot.

“The vast majority of properties in the central city have real market values that are much higher than assessed values, so drops of 50% or more would generally be required in order to impact property tax revenue,” Wilkerson says. He’s not sure that will happen. He sees some green shoots: “We have many examples of central city neighborhoods with a mix of residential and commercial uses that are thriving.”

The 16 properties with documented distress are listed on the map that follows at the end of this story. We’ve done short profiles of three we think are emblematic. One, the Commonwealth, is historic, and the owners took maybe the biggest haircut (Wall Street’s favorite term for a loss) in town. Another, Aspect on Sixth, got an expensive face-lift at exactly the wrong time. The final one, Montgomery Park, is enormous and appears to be teetering.

Almost everyone we talked to said the worst is yet to come for Portland real estate. “The dam is breaking,” said one property owner who declined to be named.

If that’s the case, the Death List will grow, and our map will bleed more red.

Building: Montgomery Park

Address: 2701 NW Vaughn St.

Year Built: 1921

Square Footage: 745,000

Owner: LLC controlled by Unico Properties

Situation: Market value is 27% less than last sales price ($255 million); liens.

Back in the day, Montgomery Park was a Montgomery Ward department store and catalog warehouse. It was the biggest building in the city when it was built.

The retailer cleared out in 1985 when Bill and Sam Naito bought the place and turned it into offices and a convention center. It’s been an office complex ever since.

Seattle-based Unico bought Montgomery Park for $255 million in April 2019. Back then, interest rates were low, and tech companies were migrating from downtown San Francisco to downtown Portland to take advantage of lower rents and the haute-hipster lifestyle.

But COVID-19 arrived, and tech firms were among the first to send workers home indefinitely. The market for Portland real estate dried up. Now, Montgomery Park has a market value of $187,281,980, according to county records, down 27% from what Unico paid.

So far, there’s no sign that Unico, which owns 17 properties in Portland, is going to default. It’s up to date on its taxes, having paid $1.8 million in 2022. But there are signs of distress. As first reported by the Portland Business Journal, Turner Construction filed a construction lien against Montgomery Park in June, claiming it’s owed $2.1 million for building improvements. A subcontractor, Culver Glass Co., filed a lien for $167,407.50.

Turner’s lien says Unico planned to pay the construction company $89.9 million for a 2022 project called “Unico-Montgomery Park Building Repositioning.” Contractors file liens when they are having trouble getting paid. It’s something of a last resort because no one wants to piss off a client. Unico declined to comment on the matter, as did Turner. Neither Culver Glass nor Turner returned a call seeking comment.

Building: Commonwealth Building

Address: 421 SW 6th Ave.

Year Built: 1948

Square Footage: 219,742

Owner: Commonwealth Property Owner LLC

Situation: Auctioned for $15 million on July 18

Another interesting thing about the death lists being passed around town is that none of Portland’s old-line real estate families is on them. There are no Menashes, no Goodmans. No Ameses.

That may be because they’ve owned their properties for years and have no debt on them. Bob Ames, for one, says he owns his buildings outright.

“I’m laughing because I don’t have any debt,” Ames says.

Most of the people in trouble are from out of town, and they often bought during the bubble years from 2014—when Portland rebounded from the last crash—to 2020. And they often used a lot of borrowed money, which was cheap at the time.

Case in point is the 14-story Commonwealth Building. Completed in 1948, it was designed by Pietro Belluschi, the Italian-born architect who became dean of the MIT School of Architecture & Planning and helped design New York’s Pan Am Building. Commonwealth put Portland on the architectural map because it was one of the first sealed, air-conditioned skyscrapers ever built. It was placed on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1976.

KBS Growth & Income REIT, based in Newport Beach, Calif., bought the Commonwealth from Unico (see above) for $69 million in June 2016. At the time, Commonwealth had 25 tenants and occupancy of 94%, bringing in $4.8 million a year, according to filings with the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. On average, tenants had about four years left on their leases.

KBS refinanced in 2018, taking an adjustable-rate loan of $51.4 million on the property from Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. Then, the pandemic and the protests hit, and tenants decamped. KBS found itself upside down. Loans were coming due, and the building was worth less than the loan amount, KBS said. Worse yet, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to quell inflation, sending KBS’s adjustable mortgage to 10.66%, according to SEC filings.

KBS blamed Stumptown. “Given the depressed office rental rates and the continued social unrest and increased crime in downtown Portland where the property is located, the company does not anticipate any near-term recovery in value,” KBS chief financial officer Jeffrey K. Waldvogel said in a regulatory filing Feb. 16.

By March of this year, KBS figured the Commonwealth was worth less than half of the $47.8 million that it still owed MetLife. Like many real estate investors in this situation, KBS stopped making its payments and sent the keys to Commonwealth to MetLife, which sold it at auction to a MetLife affiliate, KBS said, likely meaning there was no other interested buyer, on July 18.

The auction price was just $15 million, according to Multnomah County records. That’s little more than a fifth of what KBS paid for a prized architectural property just seven years ago. And it gets worse. Commonwealth helped sink KBS Growth & Income REIT entirely. In May, its shareholders approved a plan to liquidate, selling assets, paying debts, and closing the company.

Building: Aspect on Sixth

Address: 400 SW 6th Ave.

Year Built: 1961

Square Footage: 221,232

Owner: REEP-OFC Aspect OR LLC

Situation: Transferred to lender in November for $35.7 million, little more than half of what developers SteelWave and Barings paid in 2017.

Most Portlanders probably know Aspect on Sixth as the Camera World building because of the photography store on the first floor, which closed in 2016.

The building is a shape-shifter, and it’s been in trouble before.

First National Bank of Oregon bought the lot in 1957 and put up a five-story headquarters. First National (now part of Wells Fargo) moved out and sold the building to Schnitzer Investment Co. in 1972. Four years later, Schnitzer sold to First Farwest Life Insurance.

Farwest sold in 1987 but remained a tenant, and when the insurer became insolvent, it took its old headquarters down with it. The owner couldn’t pay the mortgage, and the building ended up in the hands of John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance in 1990.

Two years later, the building got a major face-lift. Investors added five new floors on top and clad the building in aluminum and stainless steel to make it look more modern.

In November 2017, SteelWave, a California-based developer, teamed up with Barings, a subsidiary of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company, to buy the building for $68 million. SteelWave spent millions more on renovation, upgrading the fitness center with something called “Moonshadow” glass that let gym users look into the lobby, but not vice versa.

SteelWave turned the Camera World into a bar and suspended a cube made of four flat panel screens that translate bar noise into colors and shapes, according to an account of the remodel by R&H Construction, the company that did all the work.

R&H says it rushed to get the building—by then called Aspect on Sixth—done by the spring of 2019. SteelWave and Barings scored in January 2020 when payments company Block, formerly called Square (for the little white boxes you swipe your credit card through at the coffee shop), signed a lease for the top three floors: 64,110 square feet.

John Ockerbloom, head of U.S. real estate at Barings, said the lease validated the business plan to “create a highly amenitized, lifestyle work environment that is attractive to today’s leading technology and creative companies.”

That same month, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the first case of COVID-19 in the U.S., just up Interstate 5 in Washington state.

It’s unclear from the paper trail what happened to Aspect. SteelWave and Barings didn’t return messages seeking comment. But records show that New York Life, the insurance company, often partners with SteelWave on projects, providing financing. Insurance companies like real estate because, usually, it throws off predictable revenue in the form of rent.

Roger Braxton, a vice president at New York Life, filed a document with Multnomah County showing that the company transferred a loan on Aspect to an LLC with the same address as New York Life on Nov. 9, 2022. The county’s website shows a sale around the same date for $35.7 million, little more than half of what SteelWave and Barings paid for Aspect just four years ago.

Someone lost money on the deal, likely SteelWave, Barings, and maybe New York Life. As the Death List shows, whoever that someone is, they’re not alone.

Office Space

Of the 40 properties on “death lists,” WW confirmed via public records that these 16 were in distress. Here’s where they are located, and what kind of trouble they’re in.

1. Montgomery Park

Address: 2701 NW Vaughn St.

Owner: LLC controlled by Unico Properties

Market Value: $187.3 million

Situation: Market value is 27% less than last sales price ($255 million); liens.

See above right for more information.

2. Make

Address: 2151 NW Savier St.

Owner: Cred Slabtown II LLC

Market Value: $42.2 million

Situation: Turned over to lender in lieu of foreclosure

3. Field Office

Address: 2035 NW Front Ave.

Owners: LLC controlled by Goldman Sachs and Lincoln Property

Market Value: $62.7 million

Situation: Defaulted, loan going to auction

4. Mason Ehrman Building & Annex

Address: 208 & 234 NW 5th Ave.

Owner: PFP 6 Mason Ehrman LLC

Market Value: $7.1 million

Situation: Foreclosed

5. Historic Bank Block

Address: 309 SW 6th Ave.

Owner: BDS IV OR Historic Bk Block LLC

Market Value: $27.1 million

Situation: Turned over to lender in lieu of foreclosure

6. Commonwealth Building

Address: 421 SW 6th Ave.

Owner: Affiliate of Metropolitan Life Insurance Co.

Market Value: $73.9 million

Situation: Auctioned for $15 million on July 18.

7. Aspect on Sixth

Address: 400 SW 6th Ave.

Owner: REEP-OFC Aspect OR LLC

Market Value: $52.6 million

Situation: Transferred in November for $35.7 million, little more than half of what developers SteelWave and Barings paid in 2017.

8. J.K. Gill Building

Address: 408 SW 5th Ave.

Owner: LLC controlled by Urban Renaissance Group

Market Value: $7 million

Situation: In receivership

9. Greek Cusina (closed)

Address: 418 SW Washington St.

Owner: CPIF PDX LLC

Market Value: $3.2 million

Situation: Market value is 46% below last sales price ($6.1 million); lien.

10. Hamilton Building

Address: 529 SW 3rd Ave.

Owner: Affiliate of Manchester Capital Management

Market Value: $7.4 million

Situation: In receivership

11. Loyalty Building

Address: 317 SW Alder St.

Owner: Affiliate of Manchester Capital Management

Market Value: $15.9 million

Situation: In receivership

12. Jackson Tower

Address: 800-818 SW Broadway

Owner: CRP Properties Inc., an affiliate of JPMorgan Chase

Market Value: $12.3 million

Situation: Defaulted, sold at auction for $7.5 million to creditor

13. Sixth + Main

Address: 1050 SW 6th Ave.

Owner: LLC controlled by Unico Properties

Market Value: $73.9 million

Situation: Market value is 13% less than last sales price ($85.1 million); lien.

14. Harrison Square

Address: 1800 SW 1st Ave.

Owner: LC Harrison Square Owner LP

Market Value: $26.8 million

Situation: Market value is 49% less than last sales price ($52.8 million); loan modified.

15. The Crossing at First

Address: 2501-2525 SW 1st Ave.

Owner: Pipco-on-the-Hudson Inc.

Market Value: $55.9 million

Situation: Defaulted, sold at auction

16. Watermark I & II

Address: 4380 S Macadam Ave.

Owner: Clarity Ventures RF Portland

Market Value: $42.6 million

Situation: Market value is 26% less than last sales price ($57.5 million); loan extended.