Last November, Portland voters chose to overhaul city government.

As a result, a city administrator in January 2025 will take over day-to-day functions like pothole filling and trash pickup. That same day, 12 City Council members—more than double the current number—will take office to make policy for the city.

Each of the 12 will represent one of four brand-new geographic districts and will be elected using a voting system that ranks candidates by order of preference, like an Oscar ballot.

Three weeks ago, the city released maps of the new districts. The campaigns for who will occupy the seats in those districts began the minute the ink dried.

While the candidates themselves debut, the more important politicking is being done behind closed doors—by the political machines that have long determined who wins a seat on the Portland City Council.

But the campaign managers, strategists, and industry and labor leaders who typically play a huge role in electing candidates are without their trusted playbooks. Those were thrown out the day Portlanders approved Measure 26-228.

“It makes my head hurt a little bit,” says longtime Democratic consultant Mark Wiener.

“What we see coming together is very much what we talked about, which was democracy,” says Jenny Lee, deputy director of the Coalition of Communities of Color, which shepherded the measure, and managing director of the coalition’s political arm, Building Power for Communities of Color. “Nobody is coming in with a clear playbook.”

A great deal is at stake. This is a broken city: Its bureaus plant trees but don’t water them, pluck light posts from public parks left in darkness, and can provide little aid to the man in a sleeping bag under Interstate 405.

The vote to change Portland’s form of government was an expression of disgust with the status quo, and the lucky dozen politicians who win office in 15 months “will be the people that are being handed the keys to set up a government,” says pollster John Horvick of the Portland firm DHM Research.

Over the past two weeks, WW spoke to more than 20 key figures—campaign managers, political consultants, labor union leaders, CEOs and nonprofit executives—about next year’s City Council races.

What’s come into focus is that at least two, and maybe three, political machines are attempting to navigate this new terrain while conceding that year one of a new city government will be chaotic.

One union strategist described it like this: “My mom always said, never buy a car on its first model year. Because it’s going to be full of bugs and shitty. And this election feels the same way. It’s going to be a mess. It’s going to be weird.”

These are the six questions that will decide who sits on the City Council in 2025—and whose interests they will represent.

How difficult will it be to get elected?

Let’s say you’ve decided to run for City Council in District 3, which stretches across Southeast Portland from the east bank of the Willamette River out to Interstate 205. By the time you jump in, nine other candidates have already declared. To secure a seat, you must make it into the top three.

The threshold to win a seat is 25% + 1 of the vote.

You’re a young progressive whose top priority is ending traffic deaths. That’s likely to go over well in this district, which in recent elections has favored candidates with liberal priorities.

But other candidates’ campaigns are built on ending traffic deaths, too. You’ll have to decide: Should you link arms with your two like-minded rivals and tell voters to support all three of you on the ballot? Or do you assume that District 3 voters have an appetite for only one transportation advocate in their district, and try to separate yourself from the other two?

“You want to be an acceptable choice to everybody,” says Jake Weigler, one of the most accomplished political consultants in Portland. “If you can be in that Venn diagram, that’s a sweet spot to be in.”

On election night in November, you’re hoping to get 25% + 1 of the votes. That would mean you win a seat outright.

But if that doesn’t happen, the ranked-choice voting system means you and your opponents are in a scramble for second and third place. Voters’ second- and third-place preferences for eliminated candidates are then reallocated.

Whether you get elected now depends not only on how many people made you their top choice, but also whether you were anybody’s second or third pick.

Now imagine 60 candidates performing a similar calculus. Throw in the interest groups also thinking strategically, and you’ve got too many possible scenarios to untangle.

Longtime political onlookers estimate anywhere from 50 to 100 candidates will end up running across the four districts. (“But I don’t have a ton of confidence in that prediction,” Horvick says.) That’s as many as two dozen candidates per district.

The most candidates to run for council citywide in any election cycle in the past three decades? Twenty-one.

“There are multiple levels of strategy,” says Amy Ruiz, a consultant and lobbyist for industry groups, “that we can’t fully comprehend yet.”

A further complication: Portland’s campaign finance laws allow super PACs to spend money with few limitations, even as candidates must abide by spending caps. That means deep-pocketed patrons could play key roles in each district.

“I do not care for independent expenditure campaigns,” says Joe Baessler, political director for Oregon AFSCME, one of the most powerful unions in the state. “But it’s going to be hard to not think those are going to pop up.”

We asked Greg Goodman of Downtown Development Group, a major purseholder for business-friendly independent expenditures in recent years, about the probability of unshackled donors spending big money.

“In time and money, I would say more than likely we would get involved,” Goodman says.

Who’s running?

The annual Labor Day Picnic is where elected officials (and those who want to be) rub elbows with their union base. This year, six of the 2025 City Council hopefuls stood at the podium, stating their names and giving a little wave. To many in the crowd, the faces were entirely unfamiliar.

The fact that half a dozen people were stumping, 14 months before the election, is a testimony to the appetite for seats. The filing deadline is Aug. 27, 2024. Yet 12 candidates have already declared, and several others haven’t denied they’re running when asked by WW.

By all accounts, the seats are desirable. The pay is $133,000 annually. The blame for any failures will be diffused among 12 possible culprits, not five. Perhaps most appealing is that the new city councilors will have one job: make policy. No longer will they double as managers of city bureaus, as the current city commissioners do.

“It is a diminished role, and these new seats pay well,” Horvick says. “And people like to feel important. Being an elected official is one way to feel important.”

The likely candidates include the founder of Cuban restaurant Palomar, a chess coach, a TikTok personality, a pharmacist, and a legislative aide. None has held office before. Most are young and progressive. Few have name recognition (see “Who’s In,” page 14, for their names and brief biographies).

“Some folks want to come out early on the progressive side because they’re like, ‘I need to stake out space and clear the field,’” says Joseph Santos-Lyons, a consultant

who last year ran Jo Ann Hardesty’s unsuccessful reelection campaign. “That may or may not work.”

One of them is Tony Morse, a soft-spoken, amicable 42-year-old who’s long been involved in Democratic Party politics. A lawyer by training, he took to real estate after he started a family. He liked talking to people, and people seemed to like talking to him, too.

He’s also in recovery from substance abuse, so he started lobbying for the nonprofit Oregon Recovers and is now its policy and advocacy director. Already, he’s dubbed himself the “recovery candidate.”

“I think the city needs someone who is focused on recovery,” Morse says, “and who can forge these partnerships with the county.”

Another early declarer is Angelita Morillo. She does policy work for Partners for a Hunger-Free Oregon, and took to TikTok to explain why she’s running for City Council as she applied red lipstick and threw on a blazer—a riff on the “get ready with me” videos that are popular with young trendsetters.

“Portlanders are craving candidates that are transparent and don’t back the status quo,” Morillo tells WW. “I’ve heard firsthand from Portlanders that are most impacted by poverty in our city. I know how to take advocacy and turn it into policy.”

Expect candidates with longer résumés and more name recognition to jump in next year. Among those weighing runs: onetime Portland Mayor Sam Adams, former Multnomah County Commissioner Loretta Smith, and erstwhile City Commissioner Steve Novick.

How will the business lobby adapt?

For decades, two interest groups jockeyed for power in City Hall: labor and business.

Business interests fought to relax building regulations, lobbied against new taxes, and focused City Hall’s attention on the health of the downtown core. The Portland Metro Chamber (formerly known as the Portland Business Alliance), represents the largest employers in the city, like Nike and insurer The Standard.

The hold that business has on City Hall, even today, is apparent from its current composition: Mayor Ted Wheeler and Commissioners Mingus Mapps and Rene Gonzalez were strongly backed by the business community.

As the charter measure rocketed toward the ballot last year, the chamber unsuccessfully fought its validity in court. The group saw the measure as a threat to its steady influence.

Once the measure passed, the chamber pivoted. It hired Doug Moore, a soft-spoken but blunt political operative who led the Oregon League of Conservation Voters in the 2010s.

Moore’s task is to place moderates (he prefers the term “pragmatic problem-solvers”) on the City Council. He says he will try to build a coalition broader than just business: “It’s hard to say who will say yes and no, but I’m going to try. Politics makes for strange bedfellows.”

Moore is creating a 501(c)(3) and a 501(c)(4) nonprofit and a political action committee to ensure moderates are elected. They’ll be governed by two separate boards of directors, seats likely to be occupied mostly by business and industry leaders.

According to those familiar with Moore’s work, soft candidate recruitment has already begun—as has talk of strategy. Candidates the coalition will likely back include Eric Zimmerman, a staffer to moderate Multnomah County Commissioner Julia Brim-Edwards, who has not yet declared.

“We want to just support the best candidates. This isn’t about ideology,” Moore tells WW—adding that the chamber hired him because he’s not afraid to “give a couple bonks” on people’s heads, but he also can build a broad coalition. “This is about problem-solving.”

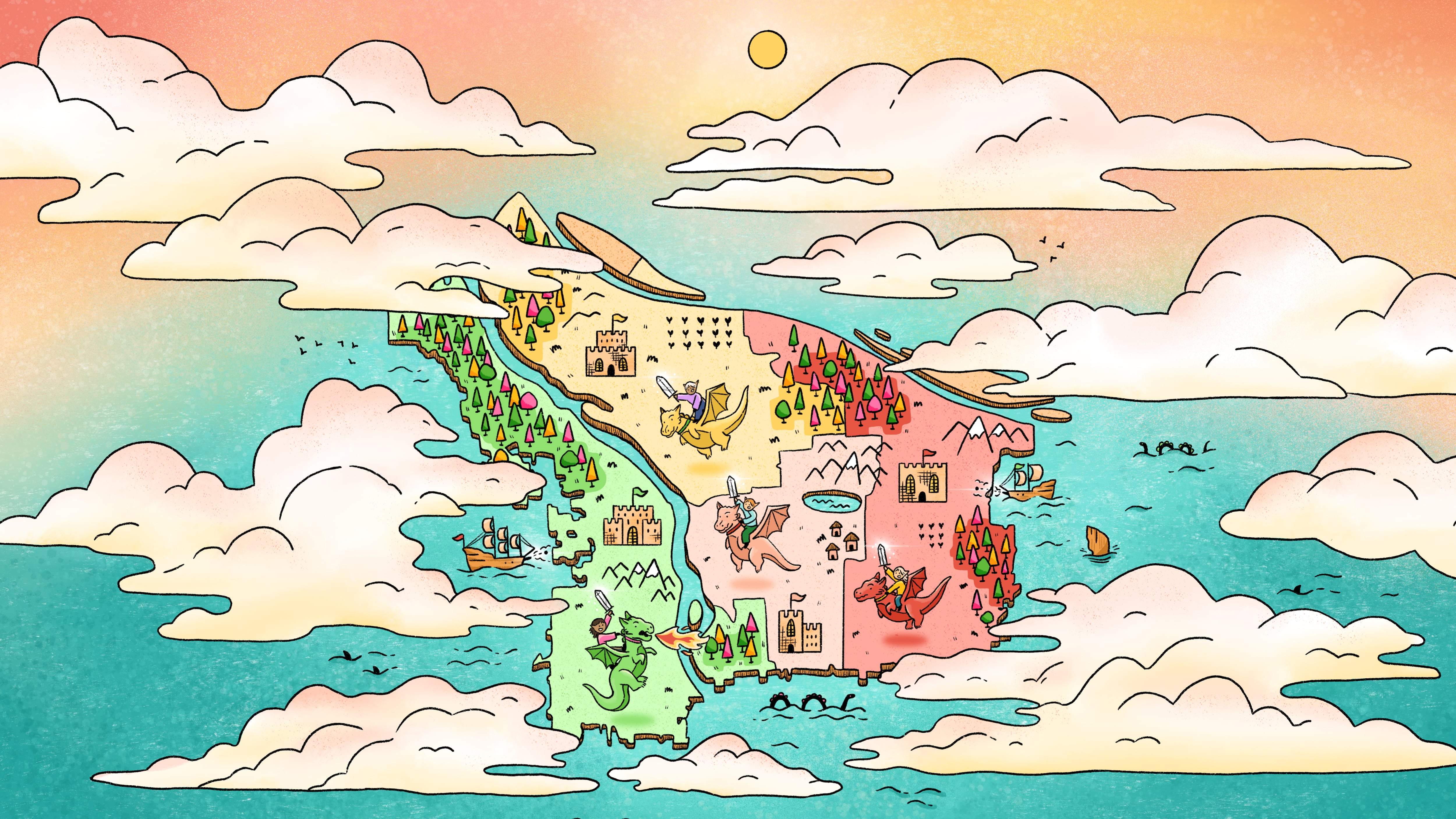

One consideration? Which districts are most likely to support moderates (see “Strongholds,” a map of power bases on page 14).

“Business is disciplined about knowing they have to focus on particular districts,” Weigler says. “The west and far east district, and then maybe they can snag a couple seats in the middle.”

How will organized labor respond?

Labor has long been the business sector’s equal, opposing force. More than 95% of the city workforce is unionized, the sheer mass making public employee unions a powerful bludgeon. So far, just one declared candidate falls directly into this category—Chris Flanary, who works for the city and is a union representative for American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 189—but there will be more.

Representatives of those groups met in a Southeast Portland conference room in mid-July to plot strategy.

A key figure at the meeting was Mark Wiener, the liberal consultant who’s played kingmaker to City Hall since at least the mid-1990s, advising Mayors Vera Katz, Sam Adams and Charlie Hales while in office and helping them out of PR pickles.

Wiener says his role isn’t clear yet: “I’m just one of a group of people figuring out the best way to proceed.”

The July meeting addressed whether a coalition of labor and social justice nonprofits was feasible —and if so, whether it would create tiers of endorsements or jointly back candidates in some other way.

“In an election where you have 25 candidates,” says Felisa Hagins, political director of Service Employees International Union Local 49, “endorsements really matter.”

Also discussed: whether they should run a slate of candidates in one district—a duo or trio that campaigns together.

Weigler says running slates could get awkward.

“It may turn out that being number one, two or three on a slate matters a lot. You don’t want them to feel like you’re picking between your children,” Weigler says. “A lot of us are still muddling through that.”

Labor leaders WW spoke to say that whether they’ll pursue slates is still up in the air. “We’re so focused on the elections that we’ve forgotten about the policies,” Hagins says. “Slates have to have an agenda. Without an agenda, what’s a slate?”

Will there be a third powerful group?

There is also the prospect of a third power base, further to the left, associated with progressive two-time mayoral candidate Sarah Iannarone. This constituency, which often overlaps with the politics of U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), includes members of local social justice nonprofits and representatives from BIPOC organizations.

Iannarone made headlines this spring by announcing plans for a candidate training school during the summer. It was quietly canceled. (Iannarone says it will commence in October.) Some progressive leaders told WW they were frustrated by that—they felt it killed momentum for the progressive base.

Labor is known for the hundreds of thousands of dollars it pours into campaigns. The racial justice nonprofits have never had deep coffers, and some of them—specifically Building Power for Communities of Color and Oregon Futures Lab—attended the July meeting with labor.

It was not lost on anyone inside the room that labor and nonprofits haven’t historically marched in lockstep on local races, Jenny Lee of Building Power says. While both groups agree on workers’ rights, unions flinch at some of the bolder experiments of the social justice left.

Earlier this year, Rep. Khanh Pham (D-East Portland) co-sponsored a “right to rest” bill that would have allowed homeless people to sleep in public spaces. Labor cringed at the bill; House Majority Leader Rep. Julie Fahey (D-Eugene), a labor Democrat, called it a “distraction” during the legislative session as Fox News pounced on it with glee.

Pham’s chief of staff, Robin Ye, 29, served on the city Charter Commission that crafted Ballot Measure 26-228 and is now running for one of the 12 City Council seats he had a hand in creating. He formerly worked for the APANO and is likely to receive endorsements from social justice nonprofits.

Ye says a coalition is critical: “We stand to lose something huge if these groups aren’t willing to work together—people not even feeling like the systemic changes we made lead to solutions. We have to be willing to work with anyone who cares about getting it right.”

WW spoke to the leaders of high-profile nonprofits about how closely they’ll align themselves with the labor unions.

Most were noncommittal.

“Labor has access to additional resources that would greatly benefit partners like us,” says Will Miller, executive director of NAYA Action Fund. “But I don’t know now if it’s even feasible.”

Further complicating the question is the uncertainty around Iannarone, who has twice rallied Portland’s left for a citywide race and was supposed to shepherd its training school. But she has been notably silent so far.

Iannarone says labor and nonprofits don’t necessarily have to form a coalition—they just have to make sure they’re not working against each other.

“The thing we all want to pay attention to is not elevate candidates that just see Portland as a place to extract profit, or to have special corporate interests use this challenging, chaotic time as an inflection point to make gains in a direction that’s counter to loving Portland,” she says. “That’s what I think should align us all.” (Iannarone says she’s not running for mayor or City Council.)

What about mayor?

In the same November 2024 election in which they’ll pick a City Council, Portland voters will also choose a new mayor.

It is in some ways a diminished job. The next mayor will hire and fire the city administrator who manages all the bureaus. But the mayor will not have a vote on the City Council under the new system and will have no veto powers (he or she will cast tie-breaking votes).

It’s unclear whether Mayor Ted Wheeler will seek a third term. A spokesperson for Wheeler tells WW, “He has not decided.” That appears true: He’s told some close associates he’s considering another term and told others he won’t run.

UPDATE: Nine hours after this story published, Wheeler announced he would not seek a third term.

City Commissioner Mingus Mapps is the only person so far to declare his mayoral candidacy. It’s widely expected that Commissioner Carmen Rubio will run, too. Commissioner Rene Gonzalez is still on the fence between running for City Council or mayor. Commissioner Dan Ryan says he’s considering a run.

Former Multnomah County Sheriff Mike Reese has also played coy about whether he’s running, but the current political mood suggests a law-and-order candidate has a chance.

Proponents of the government overhaul argued on the campaign trail that it would cause candidates to make nice with each other—so as not to alienate their opponents’ bases. It would certainly mark a change from the bitterness of recent campaigns—with Gonzalez’s bitter contest with Hardesty an example still fresh in everyone’s minds.

But the tone of the mayor’s race could set the tone for all other council races. If it turns nasty, the cold war between Portland’s power bases could go hot.

“I hope ranked-choice voting means we’ll see the edges of any political divisions soften,” says Ruiz, the industry lobbyist. “But as we get closer to November, we’ll likely see an uptick in mudslinging, with independent expenditure campaigns saying the things candidates can’t, won’t or shouldn’t.”

Strongholds

Here are a few known characteristics about Portland’s brand-new City Council districts.

DISTRICT 1

By far the most racially diverse district of the four. In the Rene Gonzalez vs. Jo Ann Hardesty runoff last fall, voters east of Interstate 205 came out strongly in support of Gonzalez.

DISTRICT 2

This district’s boundaries are similar to those of Multnomah County’s District 2, a seat long held by commissioners of color.

DISTRICT 3

Known colloquially as “The Kremlin,” inner Southeast has long been a labor stronghold. Six young progressives have already declared their candidacies here.

DISTRICT 4

Doug Moore’s business coalition thinks it can win at least two of these three seats for moderate candidates.