A statewide effort to help people wipe their past criminal records is off to a rocky start in Multnomah County.

Lawmakers passed a bill in 2021 that eliminated fees and widened eligibility criteria for “setting aside” convictions, charges and arrests—effectively hiding them from employer or landlord background checks. It’s been wildly popular.

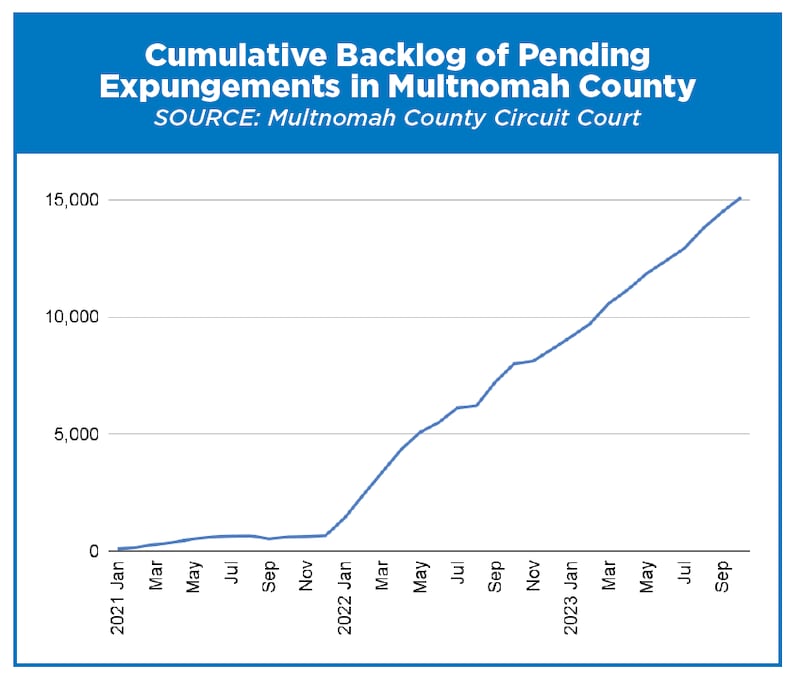

Too popular for its own good. The deluge of expungement applications has overwhelmed county and court officials in Portland. There’s now a 15,000-case backlog and a 16-month wait for an application to be reviewed.

People who expected relief are now mad. “We get phone calls almost every day saying, ‘What is going on with my expungement?’” says Sonya Good Stefani, a lawyer at Metropolitan Public Defender who runs the nonprofit’s community law division.

The backlog casts a pall over what should be a victory for criminal justice reformers, including Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt, who trumpeted the popularity of the program in an interview with WW last month. He cited the statistics as evidence that he’s doing his job well. “The number of expungements that we’re processing is incredible,” he said. “More than 10,000 last year.”

It’s certainly true that many people have already benefited from the new reforms. But thousands more have been left waiting, thanks in part to bottlenecks in his office, which, according to statute, has 120 days to review and object to an expungement request.

“We are not responding within 120 days,” admits Kelley Rhoades, a senior prosecutor in Schmidt’s office who oversees the process.

There’s been a shortage of staff and delays running federal background checks, Rhoades explains. “But we’re getting much closer,” she adds.

When someone convicted of a crime in Oregon files for expungement, a clerk in the DA’s office for that county verifies the charges are eligible and notifies any victims. (Class B felonies, like aggravated theft, are the most serious crimes eligible for expungement. Applicants must pay all outstanding fees and enter a waiting period, the length of which depends on the severity of the crime, before they can apply.) The Oregon State Police run a background check to ensure there’s been no warrants or open cases out of state. A court clerk contacts other law enforcement agencies involved and draws up the paperwork. Then a judge signs off.

Aaron Knott, the Multnomah County DA’s policy director, advocated for Senate Bill 397 in Salem. At the time, he expected the number of applications in the county to go up 60%. Instead, court data shows, it jumped from 50 in a typical month to more than 800.

The DA’s office had a single clerk winnowing down the backlog, and she soon quit. The office hadn’t asked for money to hire more. “We simply no longer had enough bodies,” Knott says.

The resulting delays have cascaded into the courtroom, where judges oversee hearings each time the DA’s office submits an objection, almost always on technicalities—like ineligible charges or a recent conviction.

“The number of days from the motion being filed to the order being entered is unacceptably high,” agrees court spokeswoman Rachel McCarthy. The court “didn’t have sufficient resources” as it grappled with other crises like an unprecedented spike in murders and a shortage of public defenders. “But we do expect to meet the expectation of 120 days once we are caught up,” she explains.

To do that, the court and the DA’s office have implemented a series of stopgap measures, including reassigning staff from other duties to review the onslaught of applications. The DA now has five expungement clerks. The court assigned staffers in its records department to focus solely on expungements and is training additional judges. The county even paid for a clerk at a local public defense firm to help review eligibility.

“We’ve started to turn the corner on this,” Knott says. “We are righting the ship.”

Chris LaFave, 57, is one of the people left waiting. He became addicted to painkillers nearly three decades ago, after being prescribed Vicodin following dental surgery. Then came heroin and stints on the street.

To fund his habit, he’d steal electronics from big-box stores, once attempting to drop in from the ceiling through an air vent. “I didn’t hurt anybody,” he says. “I was just being dumb. I thought I was a cat burglar.”

Convictions for theft and drug possession followed, most recently in 2010, which continue to haunt him to this day. After he went back to school for a degree in electrical engineering, he says, prospective employers balked at his criminal record. He now earns $15 an hour working for Avis Car Rental.

Wiping his record would have cost him thousands of dollars he didn’t have. Then, in 2022, a counselor at his methadone clinic told him about a new law that eliminated those fees, and directed LaFave to Portland Community College, which was running a free legal clinic out of its North Portland campus.

In September 2022, LaFave walked in. Volunteers took his fingerprints and walked him through the process. Using specialized software developed by a team of volunteer coders, they extracted a list of his eligible charges from state court databases. The entire process takes less than an hour.

But the wait in Multnomah County’s court system has taken 14 months, and counting. LaFave’s initial excitement has given way to frustration. His dozen or so charges in Clackamas and Washington counties have long been “set aside,” but his four felonies in Multnomah County stubbornly remain.

“I can’t wait until it’s cleared,” he says. “We’ve paid the price and earned the chance to rejoin society.”