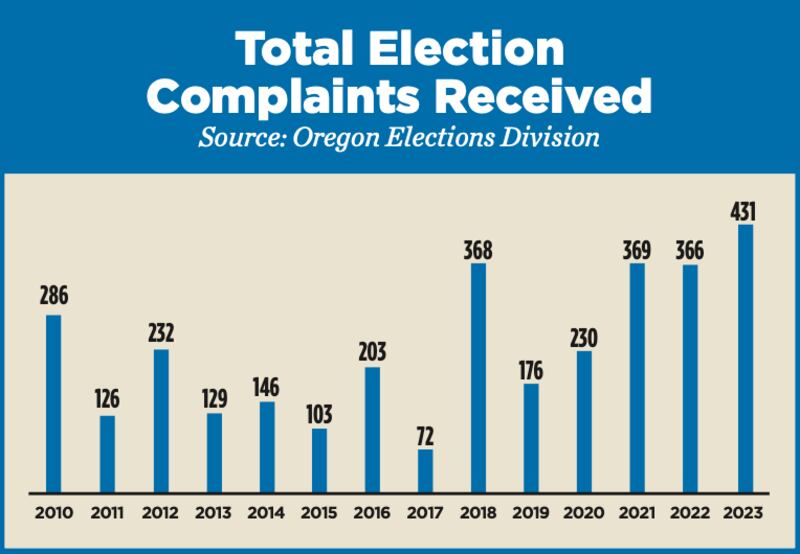

From 2010 to 2020, the Oregon secretary of state’s Elections Division received an average of 188 complaints a year.

Since 2020, that average has more than doubled to 388 per year, including a record 431 received through the first 11 months of this year—which features barely any elections.

The result: a large and growing backlog of complaints, ranging from the frivolous to the highly technical to the existential for a candidate’s campaign.

In the realm of technical complaints, for example, there was a flurry this fall challenging whether various communications about the campaign to recall state Rep. Paul Holvey (D-Eugene) included the appropriate disclosures about who paid for them. That’s important but unlikely to affect the recall (it failed last month 90% to 10%).

The agency also receives far weightier complaints, such as the one about the state’s three-year residence requirement for gubernatorial candidates that submarined Nicholas Kristof’s 2022 bid for the Democratic Party nomination for governor.

Even when complaints may appear trivial, Elections Division spokeswoman Laura Kerns says the agency adds them to the pile rather than dismissing them. “It wouldn’t be appropriate for us to make that kind of judgment call,” Kerns says.

In one of her last acts before resigning in a moonlighting scandal, former Secretary of State Shemia Fagan urged lawmakers in May to triple the number of staffers investigating complaints—from one to three. The Oregon Legislature’s Joint Ways and Means Committee on General Government approved one additional staffer.

State Rep. David Gomberg (D-Otis) happily voted for the extra position. But he is frustrated that even with it, the Elections Division will fall further behind in 2023: It has closed 235 complaints so far this year, but because 431 new complaints came in, the backlog increased by nearly 200 to a grand total of 736.

Alma Whalen, who heads complaint investigations for the Elections Division, says she’s in the second round of streamlining the intake and evaluation process to make it more efficient, but since she’s still losing ground, the agency will ask lawmakers next year for another staffer.

“We are now closing complaints at a faster rate,” Whalen says, “and we are closing more than we ever have.”

Gomberg says he’s a little frustrated at the lack of urgency, noting that the complaint backlog has grown though numerous administrations—and more than 240 complaints date back to 2021.

“How did we let things get this bad?” Gomberg asks. “I think they may need limited-duration staff to address the backlog. If so, let’s do that.”

Although nobody knows for certain why election complaints have spiked, it would be naïve not to associate it with President Donald Trump’s attempts to undermine confidence in the system. Whatever the cause, Gomberg says, failing to investigate complaints in a timely fashion only feeds skepticism in the electorate.

“The voters need to know how these issues are resolved and need to know that before they vote,” Gomberg says. “Whether [complaints] are frivolous or significant, if the state can’t resolve them, voters are harmed.”

Correction: this story originally said former Secretary of State Shemia Fagan asked for one new invesitigators. In fact, she asked for two. WW regrets the error.